As COVID-19 continues to stalk the planet, reversing years of economic progress, the recent African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) may help to stimulate recovery and transform Africa into a trading powerhouse of 1.2 billion people, and to reverse current negative trends of foreign direct investment in Africa{{1}}{{{ See, African States launch the operational phase of the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement, creating one of the largest common markets in the world, Cleary Gottlieb Alert Memorandum (July 31, 2019) Source: Cleary Gottlieb}}}. Amidst the COVID-19 global pandemic, as well as low commodity prices, inbound FDI in 2020 is forecast to decline by between 25% and 40%{{2}}{{{ World Investment Report 2020 Source: UNCTAD World Investment Report 2020}}}. AfCFTA has the potential to boost Africa’s income by $450bn by 2035, while adding $76bn in income to the rest of the world{{3}}{{{ The African Continental Free Trade Area Source: The World Bank}}}.

The new agreement is expected to promote and support FDI flows into Africa while stimulating intracontinental trading and investment. But as states look to re-write the playbook on trade and investment, it is unclear what protections – both substantive and procedural – will be offered to private investors in this new largescale African trade architecture.

This is of particular importance to the natural resources sector for example, which makes up over 40% of the continent’s exports, and has been hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. The value of greenfield project announcements in Q1 2020 fell 82% for extractive industries and 75% for petroleum and chemicals{{4}}{{{ World Investment Report 2020 Source: UNCTAD World Investment Report 2020}}}.

FDI in natural resources projects in Africa may be essential for economic development, but it is also subject to higher levels of political risk and instability than other sectors.

As COVID-19 continues to stalk the planet, reversing years of economic progress, the recent African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) may help to stimulate recovery and transform Africa into a trading powerhouse of 1.2 billion people, and to reverse current negative trends of foreign direct investment in Africa{{1}}{{{ See, African States launch the operational phase of the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement, creating one of the largest common markets in the world, Cleary Gottlieb Alert Memorandum (July 31, 2019) Source: Cleary Gottlieb}}}. Amidst the COVID-19 global pandemic, as well as low commodity prices, inbound FDI in 2020 is forecast to decline by between 25% and 40%{{2}}{{{ World Investment Report 2020 Source: UNCTAD World Investment Report 2020}}}. AfCFTA has the potential to boost Africa’s income by $450bn by 2035, while adding $76bn in income to the rest of the world{{3}}{{{ The African Continental Free Trade Area Source: The World Bank}}}.

The new agreement is expected to promote and support FDI flows into Africa while stimulating intracontinental trading and investment. But as states look to re-write the playbook on trade and investment, it is unclear what protections – both substantive and procedural – will be offered to private investors in this new largescale African trade architecture.

This is of particular importance to the natural resources sector for example, which makes up over 40% of the continent’s exports, and has been hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. The value of greenfield project announcements in Q1 2020 fell 82% for extractive industries and 75% for petroleum and chemicals{{4}}{{{ World Investment Report 2020 Source: UNCTAD World Investment Report 2020}}}.

FDI in natural resources projects in Africa may be essential for economic development, but it is also subject to higher levels of political risk and instability than other sectors.

What Will the Investment Protocol Mean for Foreign Investors?

Negotiations for the second phase of the AfCFTA were expected to resume in December, though it remains unclear whether the Investment Protocol will include investor-State dispute settlement provisions (ISDS){{5}}{{{See, G. Erasmus, How will Phase II of the AfCFTA be negotiated, ratified and implemented?, Tralac (Mar. 27, 2020) Source: Tralac U. Ewelukwa Ofodile, The African Continental Free Trade Area and Investor-State Arbitration : What Can Investors Expect And Why, Kluwer Arbitration Blog (Sept. 25, 2019) Source: Kluwer Arbitration Blog}}}. This question is likely to be the source of some controversy, particularly considering the willingness of certain AfCFTA member States to retreat from ISDS.

While the AfCFTA highlights the need to establish “clear, transparent, predictable and mutually-advantageous rules,”{{6}}{{{ AfCFTA, recitals}}} many believe this is likely to include more balanced protections for foreign investors including to ensure the preservation of the signatory states’ right to regulate in the public interest.

A trend is emerging as African states seek to renegotiate some of the near 900 bilateral and multilateral investment agreements containing ISDS, in favour of mechanisms placing greater emphasis on the states’ right to regulate and to ensure compliance with local domestic laws.

Efforts to modernize treaties are reflected in more recently concluded BITs, the so-called second and third generation BITs which emerged in the early 2000s and tended to include language with a view to balancing investor protection with States’ right to regulate. Treaties such as the 2016 Morocco-Nigeria BIT are an example of this recent trend.

Striking the right balance between achieving uniformity of trade and investment across the continent and meeting the interests of both private investors and member states is key to ensuring that a steady flow of FDI reaches the continent.

In a best-case scenario, it could result in a major step forward for Africa by effectively modernising, consolidating, and harmonizing the international legal framework of investment in Africa, which would benefit both intracontinental FDI and other FDI.

While the Investment Protocol may follow the trend of second and third generation BITs, it remains unclear what type of substantive investment protection standards will be included, as well as whether states will grant foreign investors a right of access to investor-state dispute resolution mechanisms.

International arbitration is fast developing on the continent, and at times controversial. For foreign investors, internationally established institutional rules of the ICC, LCIA or ICSID provide the comfort of perceived neutrality, stability, predictability, and independence to solve private commercial disputes or investor-State disputes{{7}}{{{ M. Ostrove, B. Sanderson, A. Lapunzina Veronelli, Developments in African Arbitration, Global Arbitration Review (Apr. 21, 2017) Source: Global Arbitration Review}}}.

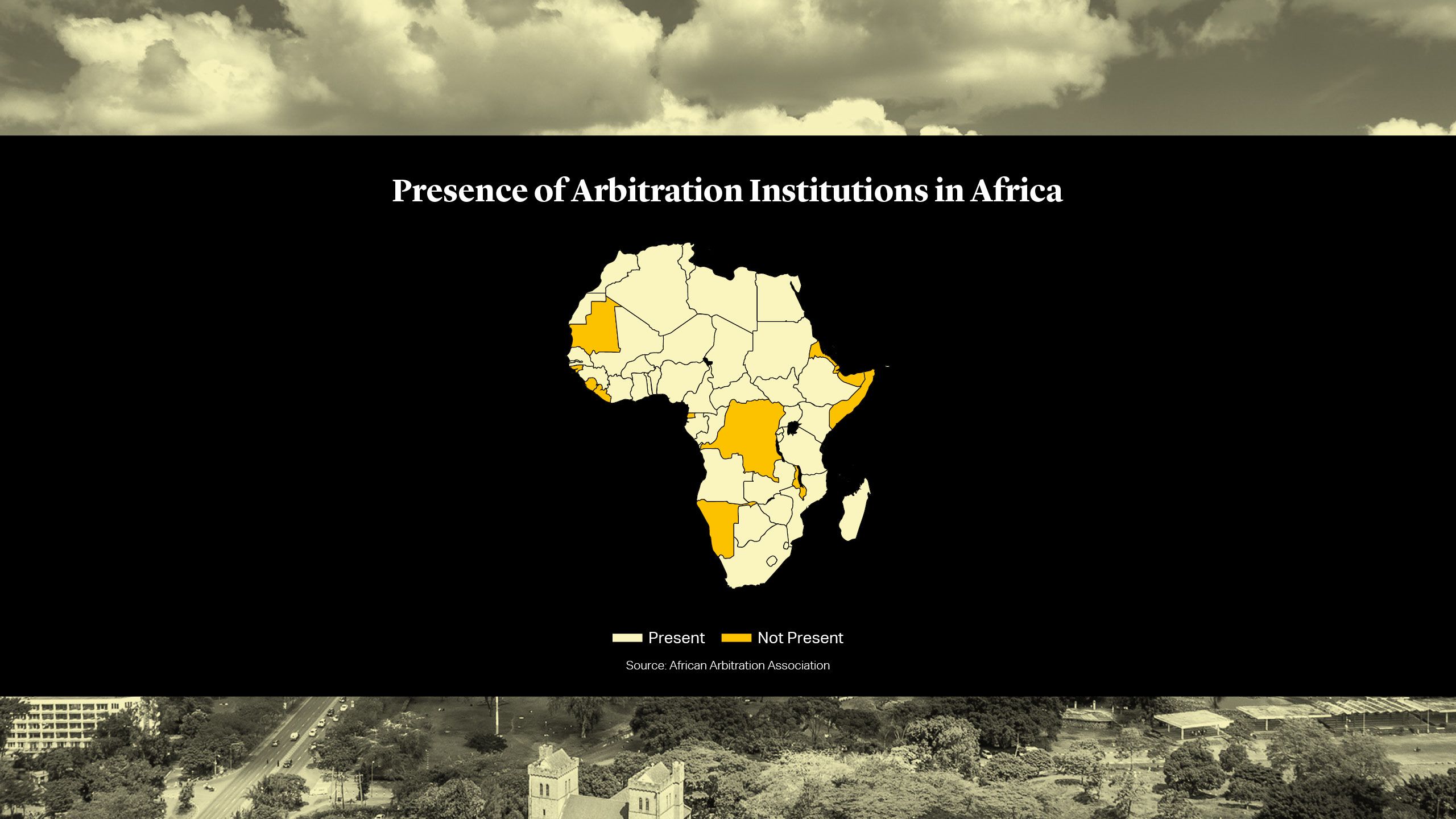

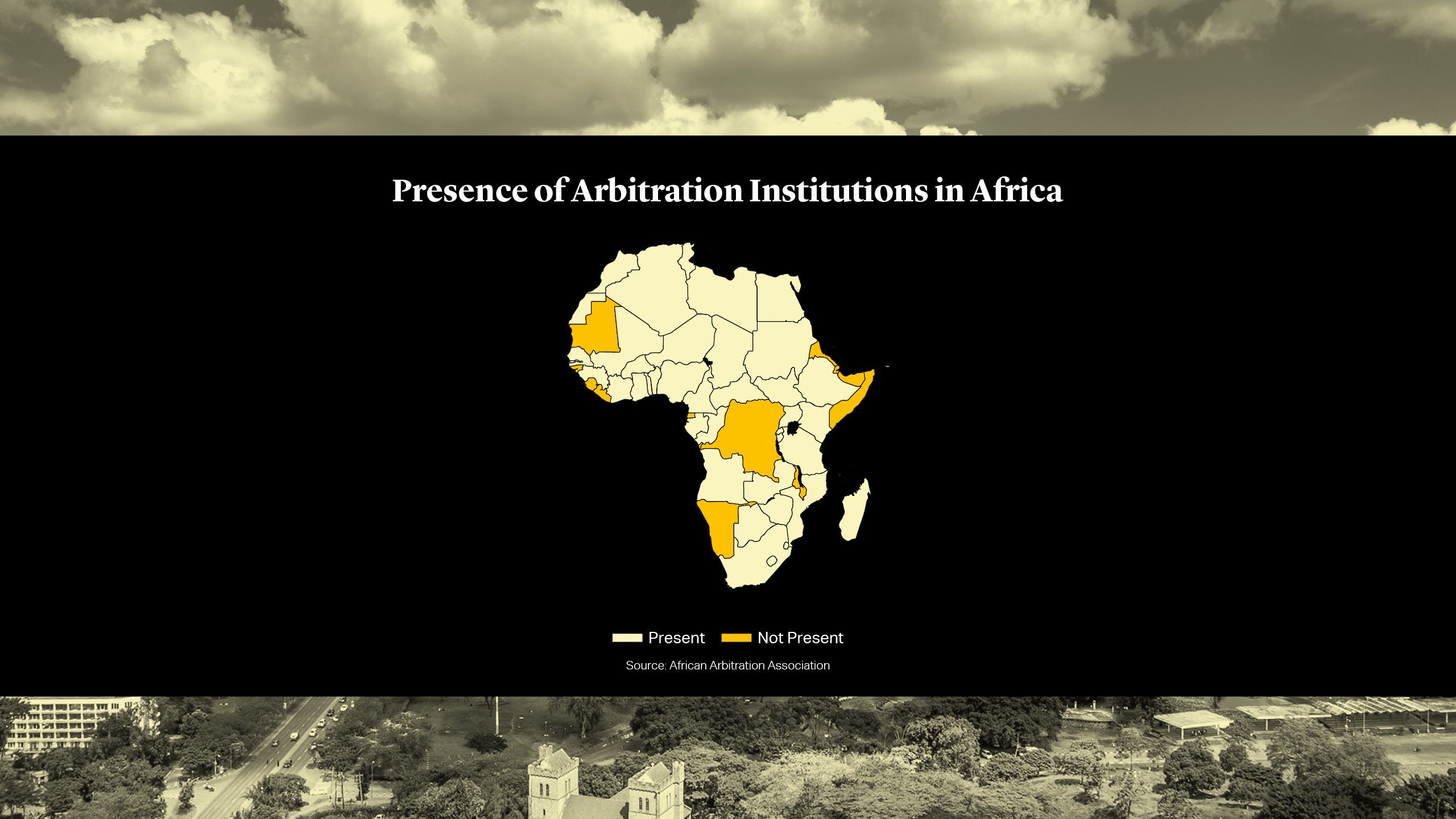

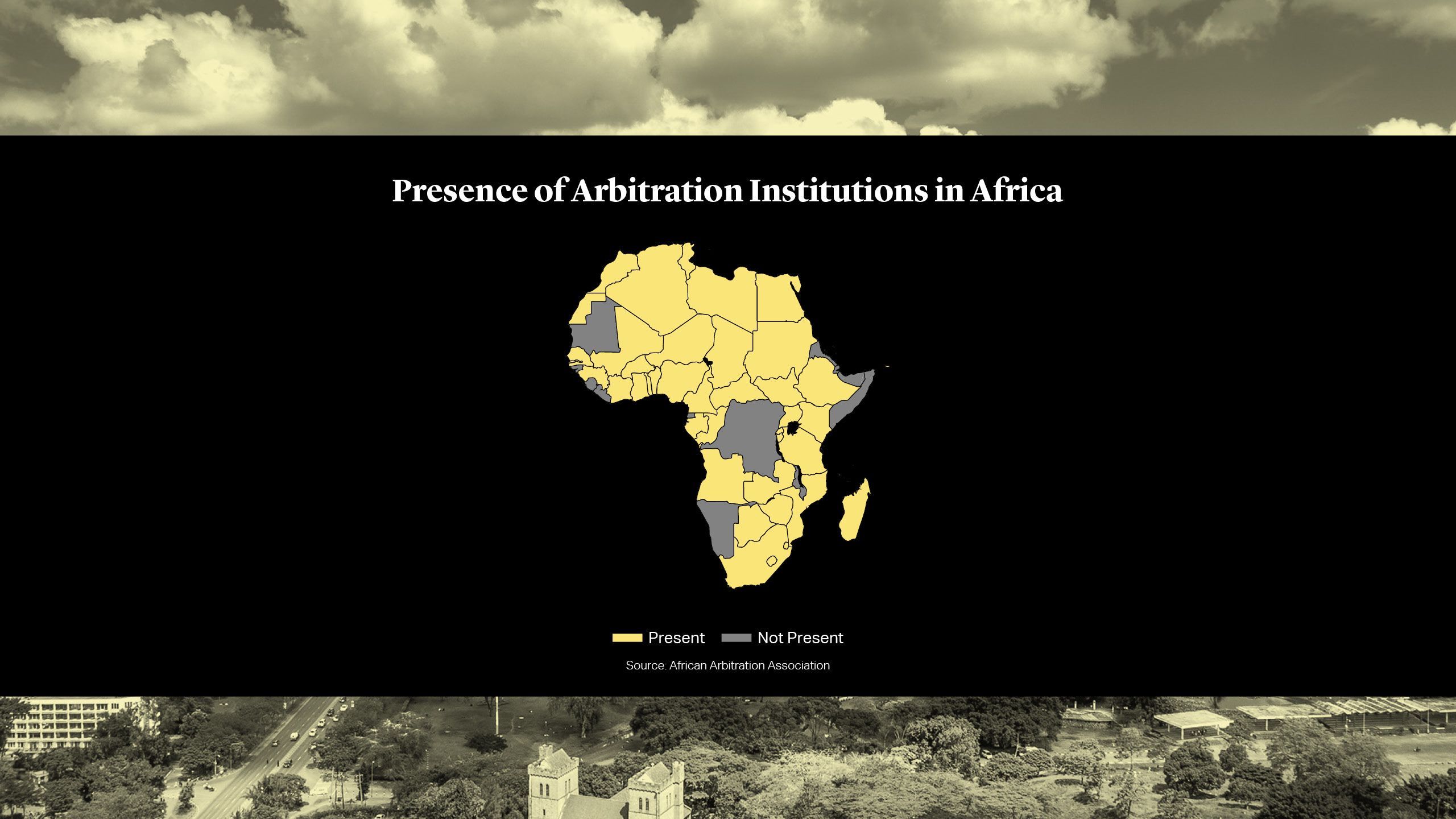

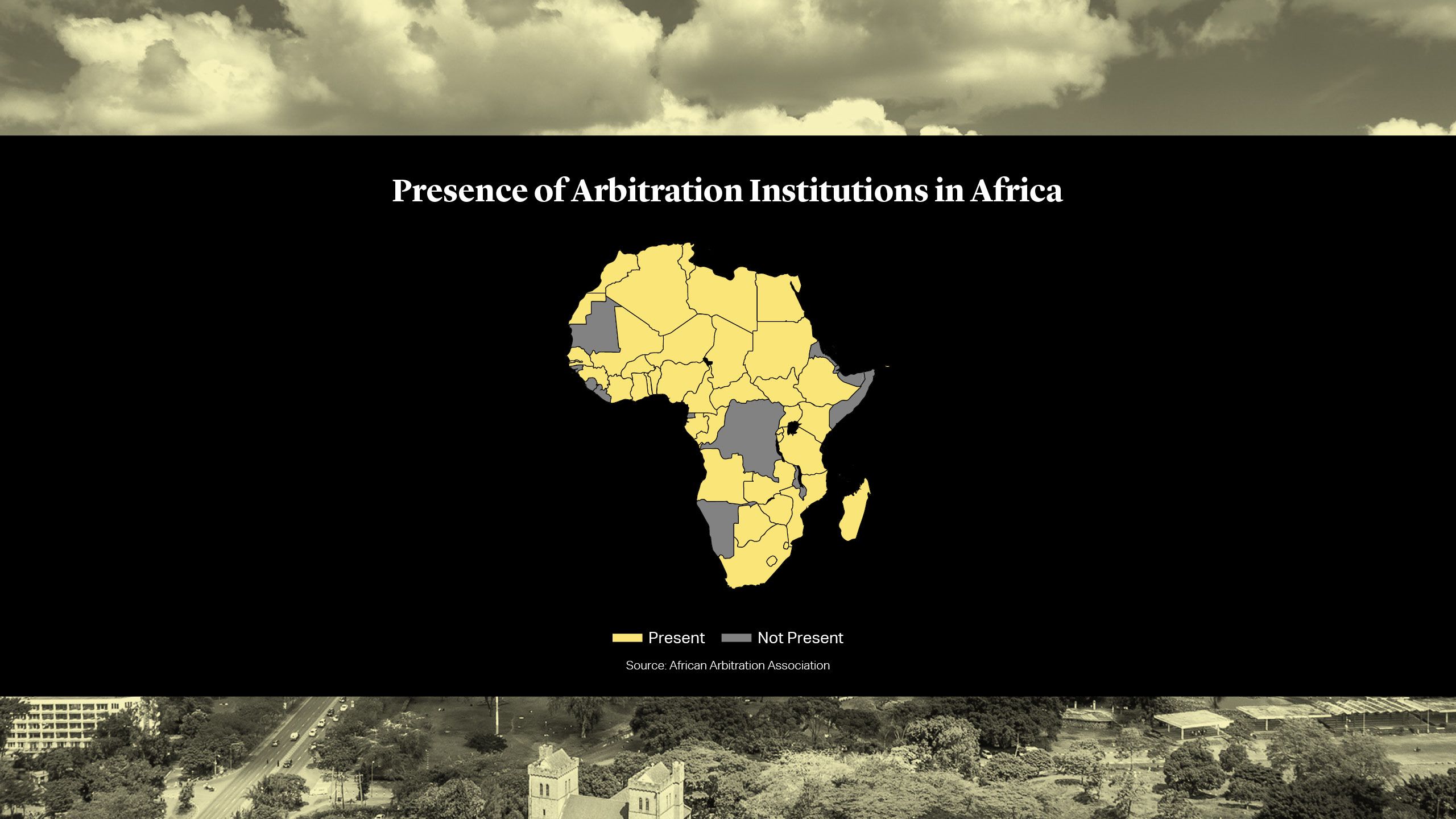

Alongside this, there is support on the African continent for further developing strong regional institutions in particular when it comes to commercial arbitration.

Tanzania is an example of a state taking a strict approach when it comes to international arbitration, whether commercial or investment, passing legislation to require investment disputes to be resolved locally{{8}}{{{N. Muchira, Tanzania cites bias as it changes law governing arbitration, The East African (Sept. 17, 2018) Source: The East African}}}. That said, only a minority of African States have chosen to ban arbitration entirely. Despite criticism of investor-state dispute settlement, most African states still offer foreign investors the option to bring proceedings before an arbitral tribunal, based on a dispute resolution clause in a contract, a domestic investment law or a bilateral or regional treaty.

Instead, a number of new investment laws (for example in Benin) as well as new arbitration laws in Ghana and South Africa point to a willingness to ensure access to arbitration for investment and/or commercial disputes.

Tanzania has also taken steps to make local arbitration more attractive, passing a new Arbitration Act 2020 in February. This reflects the increased willingness of a number of countries to provide more attractive legal frameworks to foreign investors, including when it comes to dispute resolution.

Local arbitration centres are also on the rise, which further reflects a willingness to resolve intracontinental disputes by relying on African institutional rules.

The School of Oriental and African Studies’ (SOAS) Arbitration in Africa Survey 2020 Report highlights the largely positive experience businesses have had in conducting arbitration proceedings in Africa, thereby suggesting an increasingly viable alternative to the more commonly selected international arbitral institutions in particular for mid-size disputes. In response to this trend, international arbitral institutions have taken steps to increase their presence and visibility in Africa and renewed their efforts to present themselves as the most attractive options for the resolution of intra-continental disputes. For instance, the ICC Court launched in 2018 its Africa Commission to develop the arbitral institution’s outreach and presence in the region going forward{{9}}{{{ICC Court to launch Africa Commission Source: International Chamber of Commerce}}}. Recent statistics suggest that the ICC has had success in expanding its presence on the African continent. According to the most recent ICC Dispute Resolution Statistics, the number of ICC arbitrations seated in sub-Saharan Africa almost doubled from 6 in 2018 to 11 in 2019{{10}}{{{2019 ICC Dispute Resolution Statistics Source: International Chamber of Commerce}}}.

The LCIA for its part also continues to see a growing number of African parties involved in disputes governed by the LCIA Rules{{11}}{{{LCIA 2019 Annual Casework Report, p. 10 (African parties involved in arbitrations commenced pursuant to the LCIA Rules in 2019 increased from 8% in 2018 to 10.2% in 2019) Source: LCIA 2019 Annual Casework Report}}}. In addition, the ICC and the LCIA both released new arbitral rules which encourage and facilitate electronic submissions and virtual hearings, which should positively assist with saving on both costs and time in the conduct of arbitral proceedings.

The shape of the new AFCFTA Investment Protocol will better determine the scope of the protections and remedies that will be provided to intracontinental FDI in Africa. At the same time, the increased focus of international arbitration institutions on the continent and further development of arbitral centres in South Africa, Rwanda, Egypt, Nigeria and Kenya{{12}}{{{Users of African arbitral centers frequently turn to the Cairo Regional Centre for International Commercial Arbitration (CRCICA), the Arbitration Foundation of Southern Africa (AFSA), the Kigali International Arbitration Centre (KIAC), the Nairobi Centre for International Arbitration (NCIA) or the Common Court of Justice and Arbitration (CCJA) of the OHADA, among others}}}, together with robust arbitration laws guaranteeing the neutrality of seats will mean that recourse to commercial arbitration likely remains a key route for enforcing protections both for investors outside and within the continent.

What Will the Investment Protocol Mean for Foreign Investors?

Negotiations for the second phase of the AfCFTA were expected to resume in December, though it remains unclear whether the Investment Protocol will include investor-State dispute settlement provisions (ISDS){{5}}{{{See, G. Erasmus, How will Phase II of the AfCFTA be negotiated, ratified and implemented?, Tralac (Mar. 27, 2020) Source: Tralac U. Ewelukwa Ofodile, The African Continental Free Trade Area and Investor-State Arbitration : What Can Investors Expect And Why, Kluwer Arbitration Blog (Sept. 25, 2019) Source: Kluwer Arbitration Blog}}}. This question is likely to be the source of some controversy, particularly considering the willingness of certain AfCFTA member States to retreat from ISDS.

While the AfCFTA highlights the need to establish “clear, transparent, predictable and mutually-advantageous rules,”{{6}}{{{ AfCFTA, recitals}}} many believe this is likely to include more balanced protections for foreign investors including to ensure the preservation of the signatory states’ right to regulate in the public interest.

A trend is emerging as African states seek to renegotiate some of the near 900 bilateral and multilateral investment agreements containing ISDS, in favour of mechanisms placing greater emphasis on the states’ right to regulate and to ensure compliance with local domestic laws.

Efforts to modernize treaties are reflected in more recently concluded BITs, the so-called second and third generation BITs which emerged in the early 2000s and tended to include language with a view to balancing investor protection with States’ right to regulate. Treaties such as the 2016 Morocco-Nigeria BIT are an example of this recent trend.

Striking the right balance between achieving uniformity of trade and investment across the continent and meeting the interests of both private investors and member states is key to ensuring that a steady flow of FDI reaches the continent.

In a best-case scenario, it could result in a major step forward for Africa by effectively modernising, consolidating, and harmonizing the international legal framework of investment in Africa, which would benefit both intracontinental FDI and other FDI.

While the Investment Protocol may follow the trend of second and third generation BITs, it remains unclear what type of substantive investment protection standards will be included, as well as whether states will grant foreign investors a right of access to investor-state dispute resolution mechanisms.

International arbitration is fast developing on the continent, and at times controversial. For foreign investors, internationally established institutional rules of the ICC, LCIA or ICSID provide the comfort of perceived neutrality, stability, predictability, and independence to solve private commercial disputes or investor-State disputes{{7}}{{{ M. Ostrove, B. Sanderson, A. Lapunzina Veronelli, Developments in African Arbitration, Global Arbitration Review (Apr. 21, 2017) Source: Global Arbitration Review}}}.

Alongside this, there is support on the African continent for further developing strong regional institutions in particular when it comes to commercial arbitration.

Tanzania is an example of a state taking a strict approach when it comes to international arbitration, whether commercial or investment, passing legislation to require investment disputes to be resolved locally{{8}}{{{N. Muchira, Tanzania cites bias as it changes law governing arbitration, The East African (Sept. 17, 2018) Source: The East African}}}. That said, only a minority of African States have chosen to ban arbitration entirely. Despite criticism of investor-state dispute settlement, most African states still offer foreign investors the option to bring proceedings before an arbitral tribunal, based on a dispute resolution clause in a contract, a domestic investment law or a bilateral or regional treaty.

Instead, a number of new investment laws (for example in Benin) as well as new arbitration laws in Ghana and South Africa point to a willingness to ensure access to arbitration for investment and/or commercial disputes.

Tanzania has also taken steps to make local arbitration more attractive, passing a new Arbitration Act 2020 in February. This reflects the increased willingness of a number of countries to provide more attractive legal frameworks to foreign investors, including when it comes to dispute resolution.

Local arbitration centres are also on the rise, which further reflects a willingness to resolve intracontinental disputes by relying on African institutional rules.

The School of Oriental and African Studies’ (SOAS) Arbitration in Africa Survey 2020 Report highlights the largely positive experience businesses have had in conducting arbitration proceedings in Africa, thereby suggesting an increasingly viable alternative to the more commonly selected international arbitral institutions in particular for mid-size disputes. In response to this trend, international arbitral institutions have taken steps to increase their presence and visibility in Africa and renewed their efforts to present themselves as the most attractive options for the resolution of intra-continental disputes. For instance, the ICC Court launched in 2018 its Africa Commission to develop the arbitral institution’s outreach and presence in the region going forward{{9}}{{{ICC Court to launch Africa Commission Source: International Chamber of Commerce}}}. Recent statistics suggest that the ICC has had success in expanding its presence on the African continent. According to the most recent ICC Dispute Resolution Statistics, the number of ICC arbitrations seated in sub-Saharan Africa almost doubled from 6 in 2018 to 11 in 2019{{10}}{{{2019 ICC Dispute Resolution Statistics Source: International Chamber of Commerce}}}.

The LCIA for its part also continues to see a growing number of African parties involved in disputes governed by the LCIA Rules{{11}}{{{LCIA 2019 Annual Casework Report, p. 10 (African parties involved in arbitrations commenced pursuant to the LCIA Rules in 2019 increased from 8% in 2018 to 10.2% in 2019) Source: LCIA 2019 Annual Casework Report}}}. In addition, the ICC and the LCIA both released new arbitral rules which encourage and facilitate electronic submissions and virtual hearings, which should positively assist with saving on both costs and time in the conduct of arbitral proceedings.

The shape of the new AFCFTA Investment Protocol will better determine the scope of the protections and remedies that will be provided to intracontinental FDI in Africa. At the same time, the increased focus of international arbitration institutions on the continent and further development of arbitral centres in South Africa, Rwanda, Egypt, Nigeria and Kenya{{12}}{{{Users of African arbitral centers frequently turn to the Cairo Regional Centre for International Commercial Arbitration (CRCICA), the Arbitration Foundation of Southern Africa (AFSA), the Kigali International Arbitration Centre (KIAC), the Nairobi Centre for International Arbitration (NCIA) or the Common Court of Justice and Arbitration (CCJA) of the OHADA, among others}}}, together with robust arbitration laws guaranteeing the neutrality of seats will mean that recourse to commercial arbitration likely remains a key route for enforcing protections both for investors outside and within the continent.

Christopher P. Moore

Partner

London

T: +44 20 7614 2227

New York

T: +1 212 225 2836

cmoore@cgsh.com

V-Card

Laurie Achtouk‑Spivak

Counsel

Paris

T: +33 3 40 74 68 00

lachtoukspivak@cgsh.com

V-Card

Naomi Tarawali

Associate