When Zambia failed to make a $42.5mn coupon payment on a $3bn Eurobond in October 2020, it became the first African sovereign to default on its debt since the start of the coronavirus pandemic. But for many, this was no surprise.

Plunging copper prices, poor fiscal discipline and Kwacha weakness had raised concerns about the resource-rich country’s ability to service its $12bn debt stock long before the coronavirus hit. Zambia had borrowed heavily from myriad sources, including at least $3bn from China, the terms of which are opaque.

Sadly, Zambia’s tale is not unique on the continent and analysts expect other defaults to follow. Other commodity exporters like Angola have borrowed heavily from China and the international markets, pushing its debt to GDP ratio to 123%{{1}}{{{World Bank Macro Poverty Outlook - Angola</br>Source: Macro Poverty Outlook}}}. There has also been a substantial build-up of debt in Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Kenya.

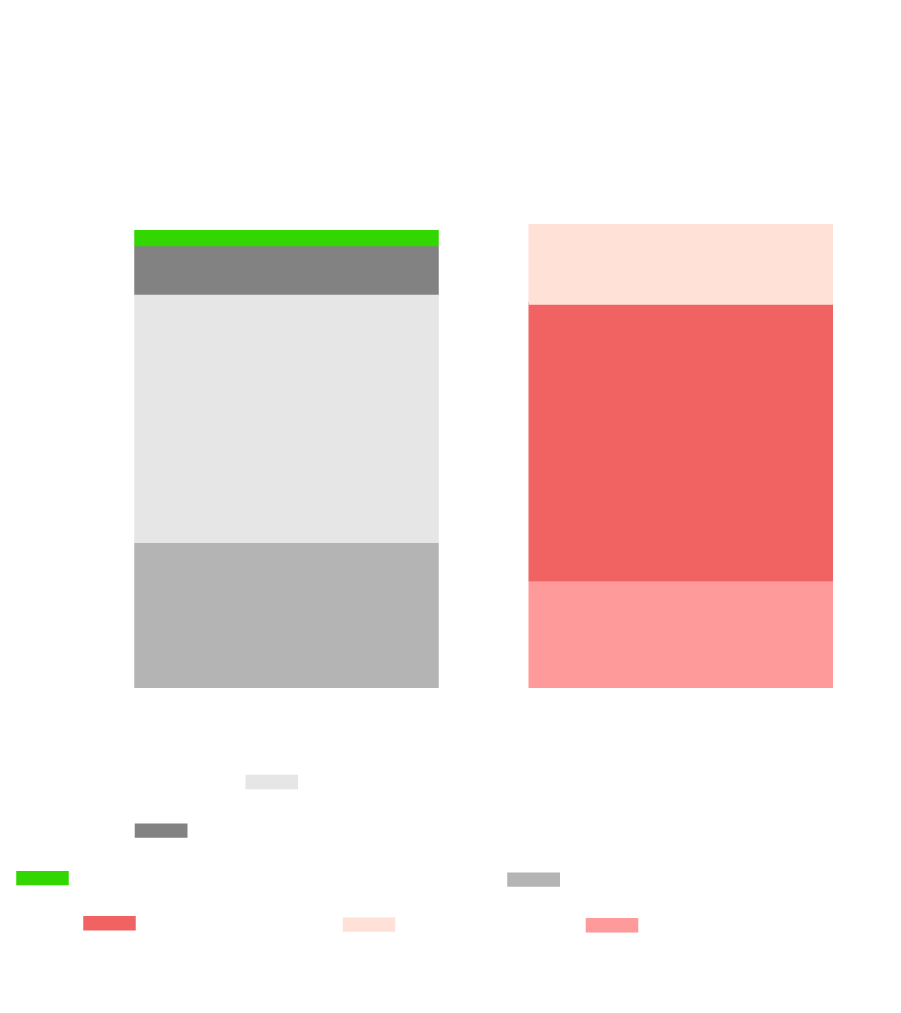

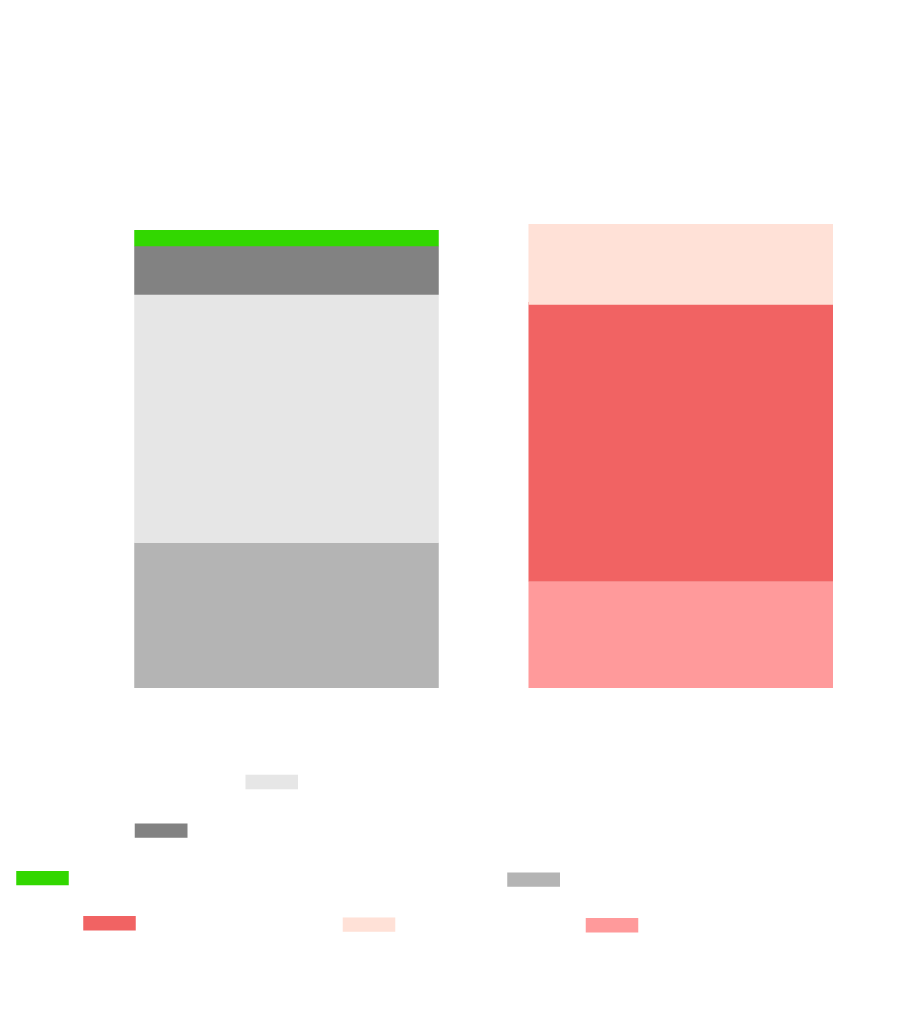

Strong bond issuance over the past decade has increased the volume of debt in international investors’ hands to $80bn in 2019 from $15bn in 2009, according to the Institute of International Finance, leaving African governments exposed to the vagaries of foreign creditors{{2}}{{{All Eyes on Africa's External Facing Needs November 2020

Source: IFF Market Snapshot}}}.

Many countries in Africa are now spending more than their total annual revenues on servicing foreign debt and in some cases, borrowing from the markets just to pay existing obligations.

Efforts So Far

The G20 has led efforts to extend bilateral relief on external debt under its Debt Service Suspension Initiative until June 2021. Almost all eligible SSA countries have benefited from this initiative, but this is seen as only a short term breather which does not address longer term debt sustainability issues. Furthermore, the DSSI efforts appear to have had little uptake from private sector lenders, which hold about 19% of the DSSI countries’ debt stock. According to a joint IMF-WBG staff note, while the IIF produced voluntary terms of reference for private sector participation in the DSSI, these terms do not appear to have been used and no private sector creditor has so far participated in the DSSI, which is perceived by private sector investors as an oversimplified binary choice{{3}}{{{Joint IMF-WBG Staff Note: Implementation and Extension of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative</br>Source: Development Committee}}}.

Several other ambitious options have also been debated throughout the year, but they have been met with roadblocks. One proposal is for the IMF to allocate more of its special drawing rights, which countries may monetise for cash, but this was vetoed by the Trump administration. Another one is for multilateral institutions, which are the biggest lenders to sovereigns around the world, to provide debt relief to the countries in need. However, any such debt cancellation could impact on the ability of the multilaterals to borrow cheaply in the capital markets. The World Bank president, David Malpass said that the World Bank’s “access to global capital markets […] would be undercut by the proposed moratorium on repayments”. The pandemic has also reignited debates about ways to reform the international legal architecture in order to facilitate sovereign debt restructurings{{4}}{{{The International Architecture for Resolving Sovereign Debt Involving Private-Sector Creditors—Recent Developments, Challenges, And Reform Options</br>Source: International Monetary Fund}}}, assuming there is any political will to do so.

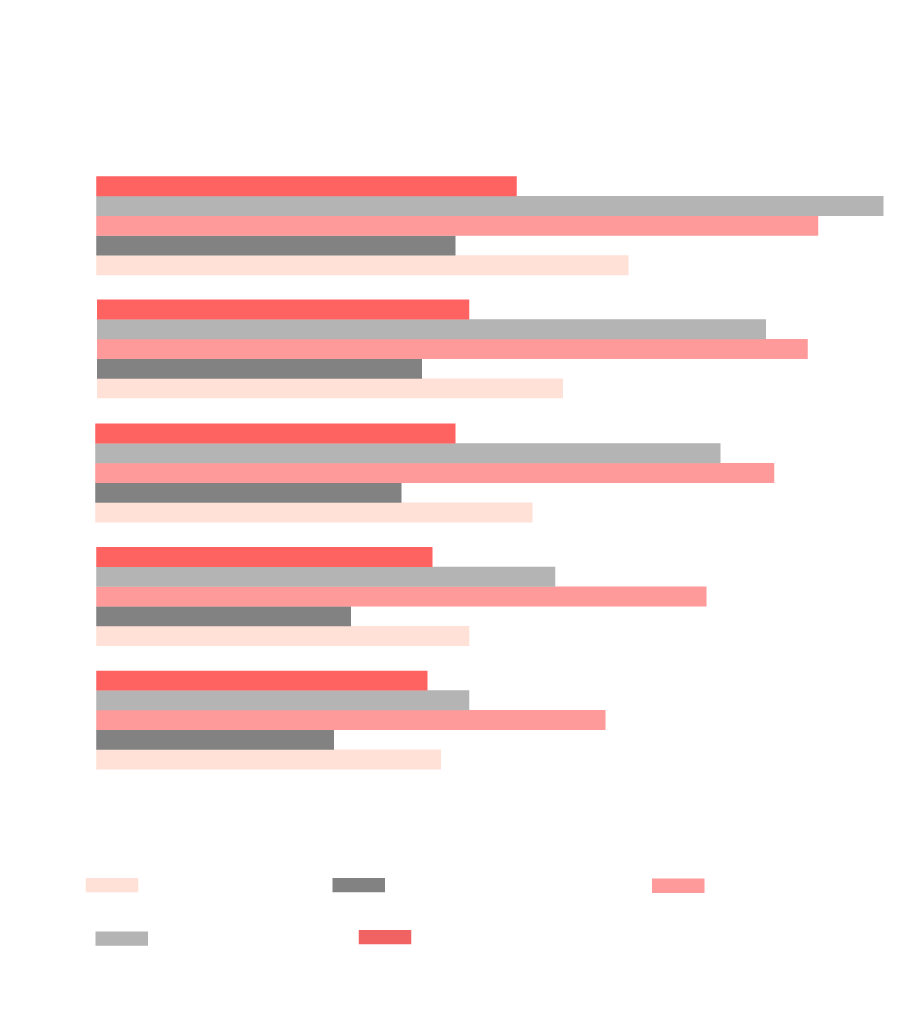

African policymakers face a difficult dilemma. Unable to rely on the fiscal muscle or monetary stimulus used to ease the pain in developed markets, sub-Saharan Africa must rely heavily on external financing to support its economic recovery. Potential external financing needs are estimated to be about $890bn with a financing gap of $290bn for the period 2020–23, the IMF says{{5}}{{{Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa</br>Source: International Monetary Fund}}}.

The IMF predicts concessional funding will only be able to meet a quarter of the continent’s financing gap while almost half will have to come from private sector creditors, meaning access to capital markets will be an essential source of funds{{6}}{{{Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa</br>Source: International Monetary Fund}}}.

Efforts So Far

The G20 has led efforts to extend bilateral relief on external debt under its Debt Service Suspension Initiative until June 2021. Almost all eligible SSA countries have benefited from this initiative, but this is seen as only a short term breather which does not address longer term debt sustainability issues. Furthermore, the DSSI efforts appear to have had little uptake from private sector lenders, which hold about 19% of the DSSI countries’ debt stock. According to a joint IMF-WBG staff note, while the IIF produced voluntary terms of reference for private sector participation in the DSSI, these terms do not appear to have been used and no private sector creditor has so far participated in the DSSI, which is perceived by private sector investors as an oversimplified binary choice{{3}}{{{Joint IMF-WBG Staff Note: Implementation and Extension of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative</br>Source: Development Committee}}}.

Several other ambitious options have also been debated throughout the year, but they have been met with roadblocks. One proposal is for the IMF to allocate more of its special drawing rights, which countries may monetise for cash, but this was vetoed by the Trump administration. Another one is for multilateral institutions, which are the biggest lenders to sovereigns around the world, to provide debt relief to the countries in need. However, any such debt cancellation could impact on the ability of the multilaterals to borrow cheaply in the capital markets. The World Bank president, David Malpass said that the World Bank’s “access to global capital markets […] would be undercut by the proposed moratorium on repayments”. The pandemic has also reignited debates about ways to reform the international legal architecture in order to facilitate sovereign debt restructurings{{4}}{{{The International Architecture for Resolving Sovereign Debt Involving Private-Sector Creditors—Recent Developments, Challenges, And Reform Options

Source: International Monetary Fund}}}, assuming there is any political will to do so.

African policymakers face a difficult dilemma. Unable to rely on the fiscal muscle or monetary stimulus used to ease the pain in developed markets, sub-Saharan Africa must rely heavily on external financing to support its economic recovery. Potential external financing needs are estimated to be about $890bn with a financing gap of $290bn for the period 2020–23, the IMF says{{5}}{{{Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa

Source: International Monetary Fund}}}.

The IMF predicts concessional funding will only be able to meet a quarter of the continent’s financing gap while almost half will have to come from private sector creditors, meaning access to capital markets will be an essential source of funds{{6}}{{{Regional Economic Outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa

Source: International Monetary Fund}}}.

Market-Based Solutions

What is clear is that there needs to be a market-based solution which ensures governments still have access to vital new capital and addresses the build-up of unsustainable debt.

Either the cost of borrowing for African countries has to be lower – through better investor education, clearer reporting, evidence of structural reform or GDP growth – or there needs to be a concessional component to financing such as a MIGA or World Bank Guarantee.

One proposal, from the Emerging Markets Investors Alliance (EMIA), is to refinance existing debt stock for countries that cannot service their debt into bonds linked to sustainable development goals (SDG){{7}}{{{Emerging Markets Investors Alliance, letter to G20

Source: Emerging Markets Investors Alliance}}}. Still in the nascent stages, it proposes payments for those bonds will be linked to policy improvements, meaning that if governments outperform their SDG objectives, the coupons will go down and their debt will become more sustainable.

The EMIA recognises that for many governments, reporting needs that are linked to compliance with SDGs are too arduous. Their aim is to reduce the debt burden on countries while also having a positive impact on development.

Tying bonds to measurable SDG objectives may also help reduce the “Africa premium” on African debt. Greater transparency and data provision will over time allow investors to more appropriately understand and price risk based on the specificities of the debtor, not broad generalisations and misconceptions that taint all countries on the continent.

Market-Based Solutions

What is clear is that there needs to be a market-based solution which ensures governments still have access to vital new capital and addresses the build-up of unsustainable debt.

Either the cost of borrowing for African countries has to be lower – through better investor education, clearer reporting, evidence of structural reform or GDP growth – or there needs to be a concessional component to financing such as a MIGA or World Bank Guarantee.

One proposal, from the Emerging Markets Investors Alliance (EMIA), is to refinance existing debt stock for countries that cannot service their debt into bonds linked to sustainable development goals (SDG){{7}}{{{Emerging Markets Investors Alliance, letter to G20 Source: Emerging Markets Investors Alliance}}}. Still in the nascent stages, it proposes payments for those bonds will be linked to policy improvements, meaning that if governments outperform their SDG objectives, the coupons will go down and their debt will become more sustainable.

The EMIA recognises that for many governments, reporting needs that are linked to compliance with SDGs are too arduous. Their aim is to reduce the debt burden on countries while also having a positive impact on development.

Tying bonds to measurable SDG objectives may also help reduce the “Africa premium” on African debt. Greater transparency and data provision will over time allow investors to more appropriately understand and price risk based on the specificities of the debtor, not broad generalisations and misconceptions that taint all countries on the continent.

Debt Transparency

Another way to help reduce borrowing costs and improve market access is to encourage greater debt transparency which would facilitate good governance and support debt sustainability.

The G20 went some way to address this when it announced a “common framework” which outlined a set of procedures for the treatment of debt in DSSI-eligible countries such as Zambia. The framework will assess whether a country’s debts are sustainable by signing it up to an IMF programme and by involving both official bilateral and commercial creditors{{8}}{{{The G20 summit and a Biden administration could lead to new initiatives for poorer countries</br>Source: Financial Times}}}. On 27 January 2021, Chad became the first country to officially request to restructure its external debt under the G20 Common Framework for debt restructuring to restore debt sustainability {{9}}{{{IMF Reaches Staff-Level Agreement with Chad on a Four-Year Program Under Extended Credit Facility (ECF) and Extended Fund Facility (EFF)</br>Source: International Monetary Fund}}}.

The IMF, together with the World Bank, says they are working on multiple fronts to enhance debt transparency by dedicating more resources to public debt reporting in borrowing countries as well as setting higher reporting requirements for its surveillance activities{{10}}{{{Current sovereign debt challenges and priorities in the period ahead

Source: International Monetary Fund}}}. The IMF has also reformed its Policy on Debt Limits in IMF-supported Programs to further raise the bar on debt disclosure to the IMF.

The Institute of International Finance and other advocacy groups are calling for a market watchdog to monitor debt accumulation, be accountable for the build-up of non-concessional debt and help governments meet the minimum requirements for debt recording, monitoring and reporting. But nothing formal has been announced or endorsed in this respect by key stakeholders as yet.

Debt Transparency

Another way to help reduce borrowing costs and improve market access is to encourage greater debt transparency which would facilitate good governance and support debt sustainability.

The G20 went some way to address this when it announced a “common framework” which outlined a set of procedures for the treatment of debt in DSSI-eligible countries such as Zambia. The framework will assess whether a country’s debts are sustainable by signing it up to an IMF programme and by involving both official bilateral and commercial creditors{{8}}{{{The G20 summit and a Biden administration could lead to new initiatives for poorer countries

Source: Financial Times}}}. On 27 January 2021, Chad became the first country to officially request to restructure its external debt under the G20 Common Framework for debt restructuring to restore debt sustainability {{9}}{{{IMF Reaches Staff-Level Agreement with Chad on a Four-Year Program Under Extended Credit Facility (ECF) and Extended Fund Facility (EFF)

Source: International Monetary Fund}}}.

The IMF, together with the World Bank, says they are working on multiple fronts to enhance debt transparency by dedicating more resources to public debt reporting in borrowing countries as well as setting higher reporting requirements for its surveillance activities{{10}}{{{Current sovereign debt challenges and priorities in the period ahead Source: International Monetary Fund}}}. The IMF has also reformed its Policy on Debt Limits in IMF-supported Programs to further raise the bar on debt disclosure to the IMF.

The Institute of International Finance and other advocacy groups are calling for a market watchdog to monitor debt accumulation, be accountable for the build-up of non-concessional debt and help governments meet the minimum requirements for debt recording, monitoring and reporting. But nothing formal has been announced or endorsed in this respect by key stakeholders as yet.

Is there Appetite for African Debt?

Since the start of the pandemic, several emerging and frontier market sovereigns such as Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Oman have tapped international markets. Emerging markets reported a record year for sovereign (and private) external issuance in 2020{{11}}{{{Anything goes in whacky world of emerging market debt</br>Source: Reuters}}}.

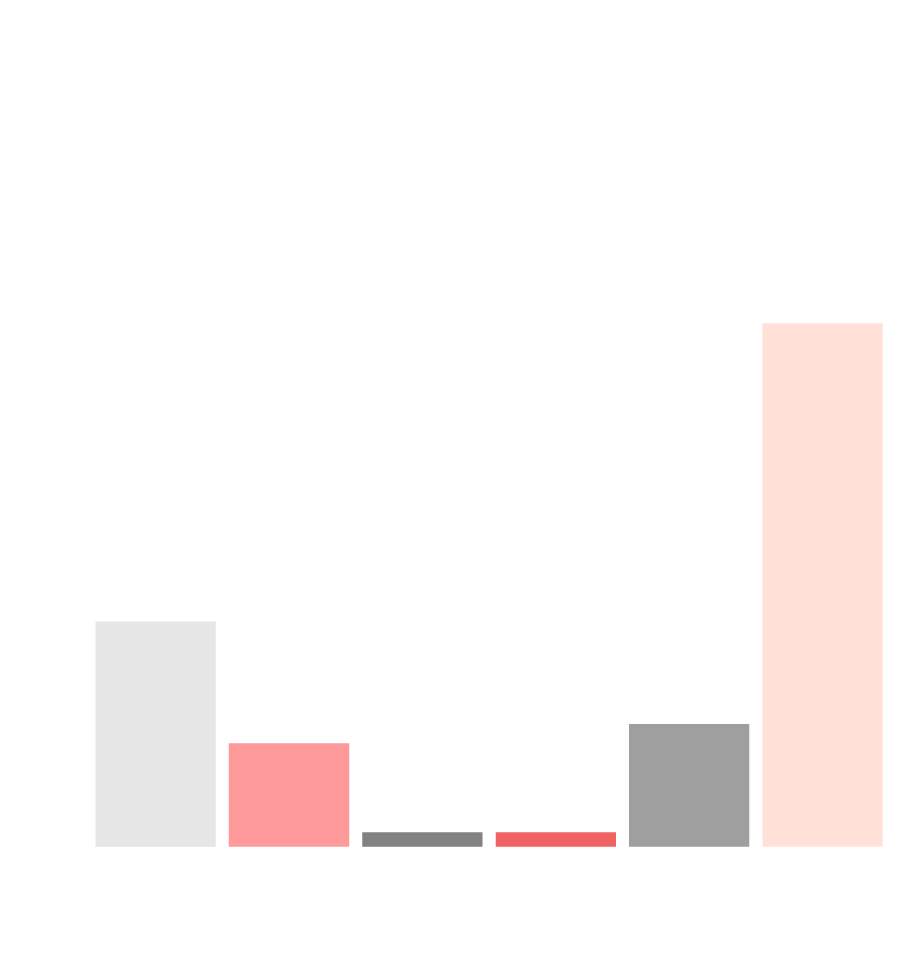

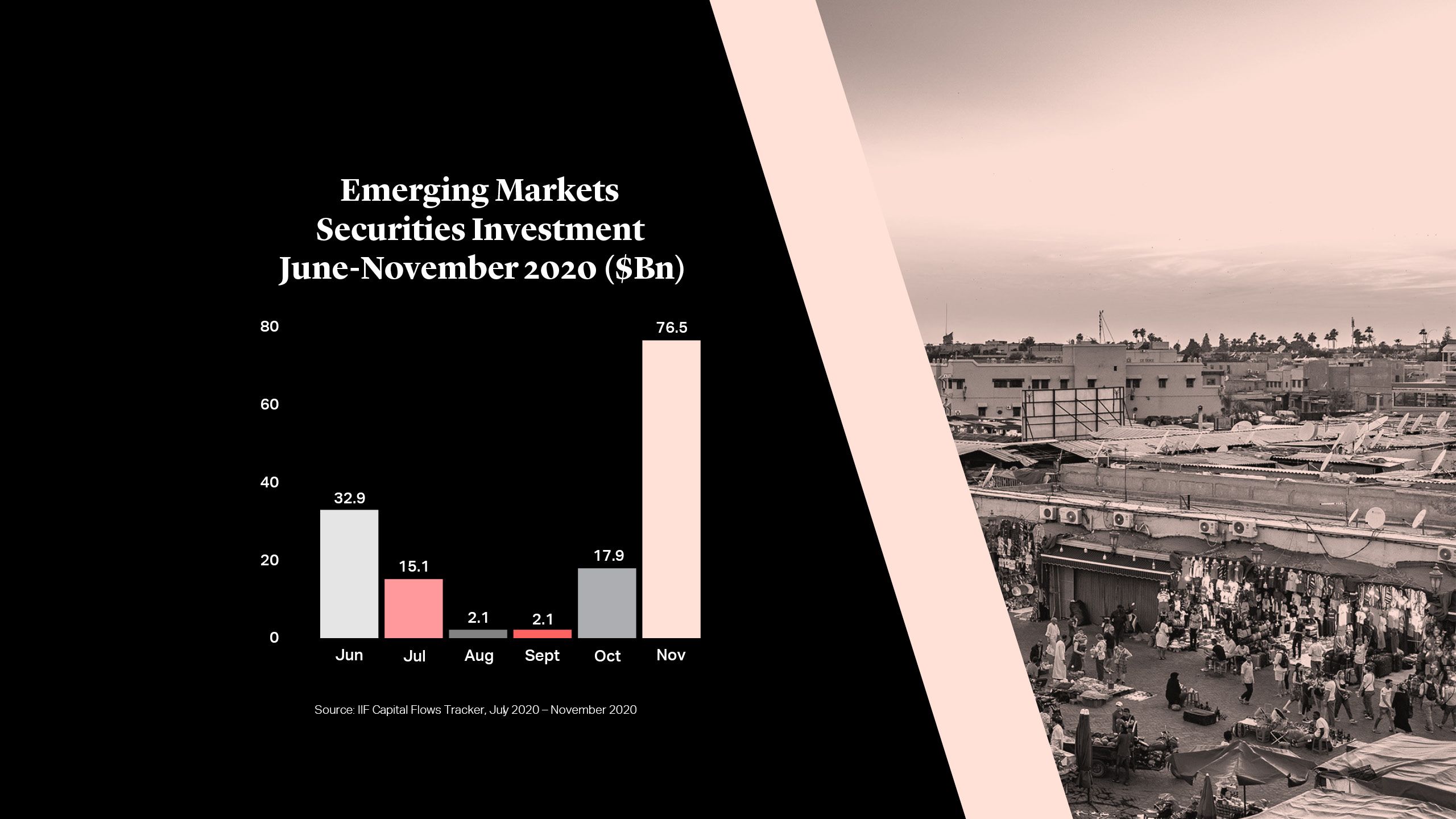

The keenly anticipated roll out of vaccines has lifted global equity markets, fuelling greater risk taking, while non-resident portfolio flows to emerging markets after large outflows in April. Overall inflows of $313bn in 2020 were just $48bn lower than in 2019{{12}}{{{IIF Capital Flows Tracker – December 2020 Back from the brink</br>Source: Institute of International Finance}}}. Emerging markets securities attracted around $76.5bn in November 2020, from $23.5bn in October, the Institute of International Finance says, driven by the improving outlook for the global economy and after Joe Biden claimed the U.S. election{{13}}{{{IIF Capital Flows Tracker </br>Source: Institute of International Finance}}}.

Nigeria’s FirstBank proved in October the market is open for a select few African corporate issuers too. FBN raised $350mn with a five year bond which was 1.7 times subscribed, though the yield of 8.625% underscores the continued high cost of borrowing for African issuers.

Bond issuance from IDA-eligible countries has been limited since the start of the pandemic, but Cote d’Ivoire’s successful €1bn bond issue in early December 2020 and successful €850mn tap issue in February 2021 and Benin’s successful €1bn bond issue in mid-January 2021 show there is demand for sub-Saharan debt and other SSA countries like Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa and Namibia are expected to follow in 2021. But for many governments, borrowing costs still remain higher than pre-pandemic levels and the wave of recent ratings downgrades is also weighing on appetite to tap capital markets despite the improvement in global liquidity. Issuers should also be wary of volatility in rates markets going forward, meaning that any approach to the capital markets must be well-timed.

While global monetary policy is likely to remain extremely accommodative until some clear signs of economic recovery emerge, a Democratic administration in the U.S. led by President Joe Biden could herald an era of tighter monetary and fiscal policy in the U.S. Some economists suggest this could prompt a 75bps-100bps spike in Treasury yields, raising the cost of dollar denominated borrowing considerably for some borrowers.

Is there Appetite for African Debt?

Since the start of the pandemic, several emerging and frontier market sovereigns such as Egypt, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Oman have tapped international markets. Emerging markets reported a record year for sovereign (and private) external issuance in 2020{{11}}{{{Anything goes in whacky world of emerging market debt

Source: Reuters}}}.

The keenly anticipated roll out of vaccines has lifted global equity markets, fuelling greater risk taking, while non-resident portfolio flows to emerging markets after large outflows in April. Overall inflows of $313bn in 2020 were just $48bn lower than in 2019{{12}}{{{IIF Capital Flows Tracker – December 2020 Back from the brink

Source: Institute of International Finance}}}. Emerging markets securities attracted around $76.5bn in November 2020, from $23.5bn in October, the Institute of International Finance says, driven by the improving outlook for the global economy and after Joe Biden claimed the U.S. election{{13}}{{{IIF Capital Flows Tracker

Source: Institute of International Finance}}}.

Nigeria’s FirstBank proved in October the market is open for a select few African corporate issuers too. FBN raised $350mn with a five year bond which was 1.7 times subscribed, though the yield of 8.625% underscores the continued high cost of borrowing for African issuers.

Bond issuance from IDA-eligible countries has been limited since the start of the pandemic, but Cote d’Ivoire’s successful €1bn bond issue in early December 2020 and successful €850mn tap issue in February 2021 and Benin’s successful €1bn bond issue in mid-January 2021 show there is demand for sub-Saharan debt and other SSA countries like Nigeria, Ghana, South Africa and Namibia are expected to follow in 2021. But for many governments, borrowing costs still remain higher than pre-pandemic levels and the wave of recent ratings downgrades is also weighing on appetite to tap capital markets despite the improvement in global liquidity. Issuers should also be wary of volatility in rates markets going forward, meaning that any approach to the capital markets must be well-timed.

While global monetary policy is likely to remain extremely accommodative until some clear signs of economic recovery emerge, a Democratic administration in the U.S. led by President Joe Biden could herald an era of tighter monetary and fiscal policy in the U.S. Some economists suggest this could prompt a 75bps-100bps spike in Treasury yields, raising the cost of dollar denominated borrowing considerably for some borrowers.