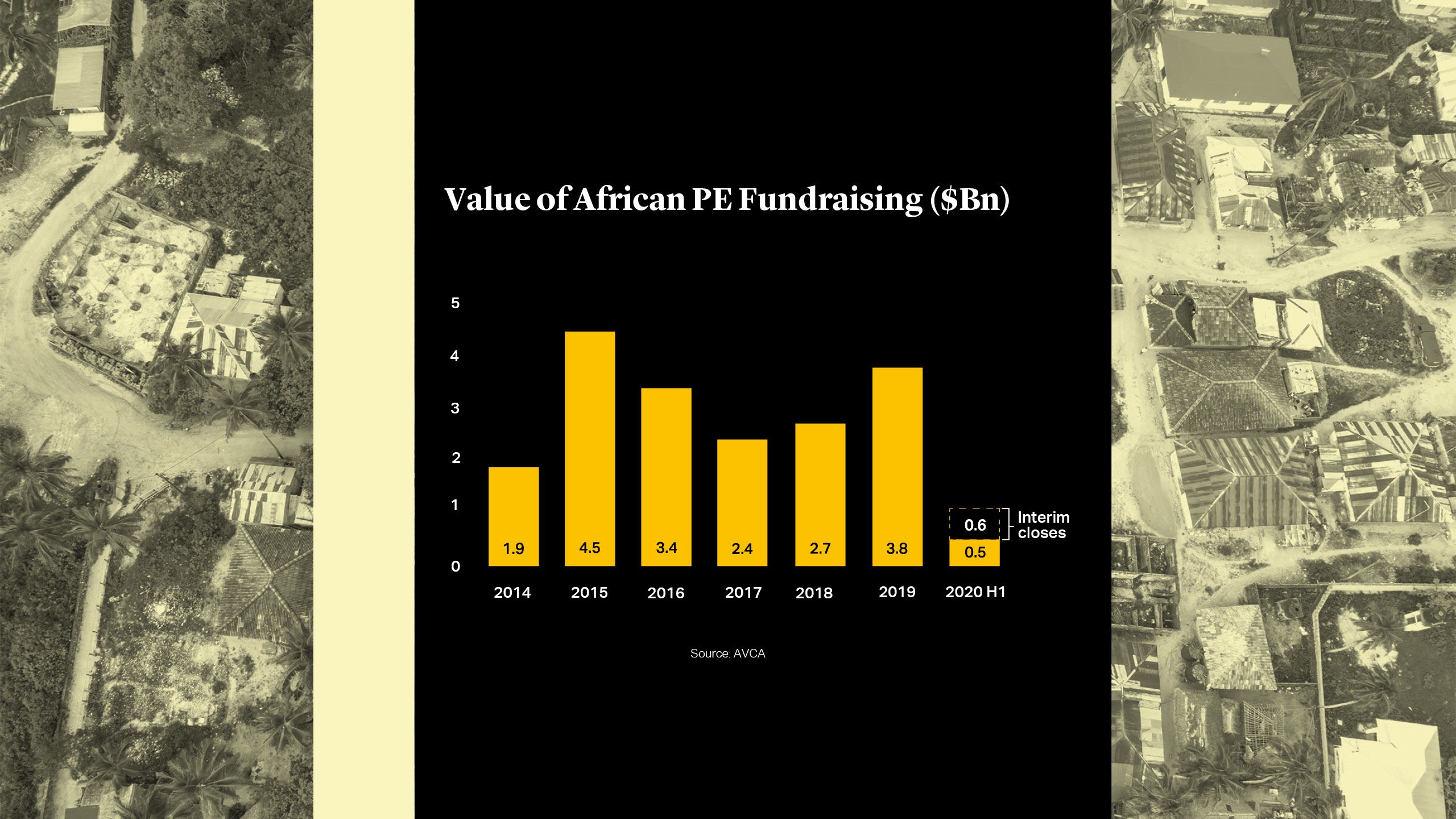

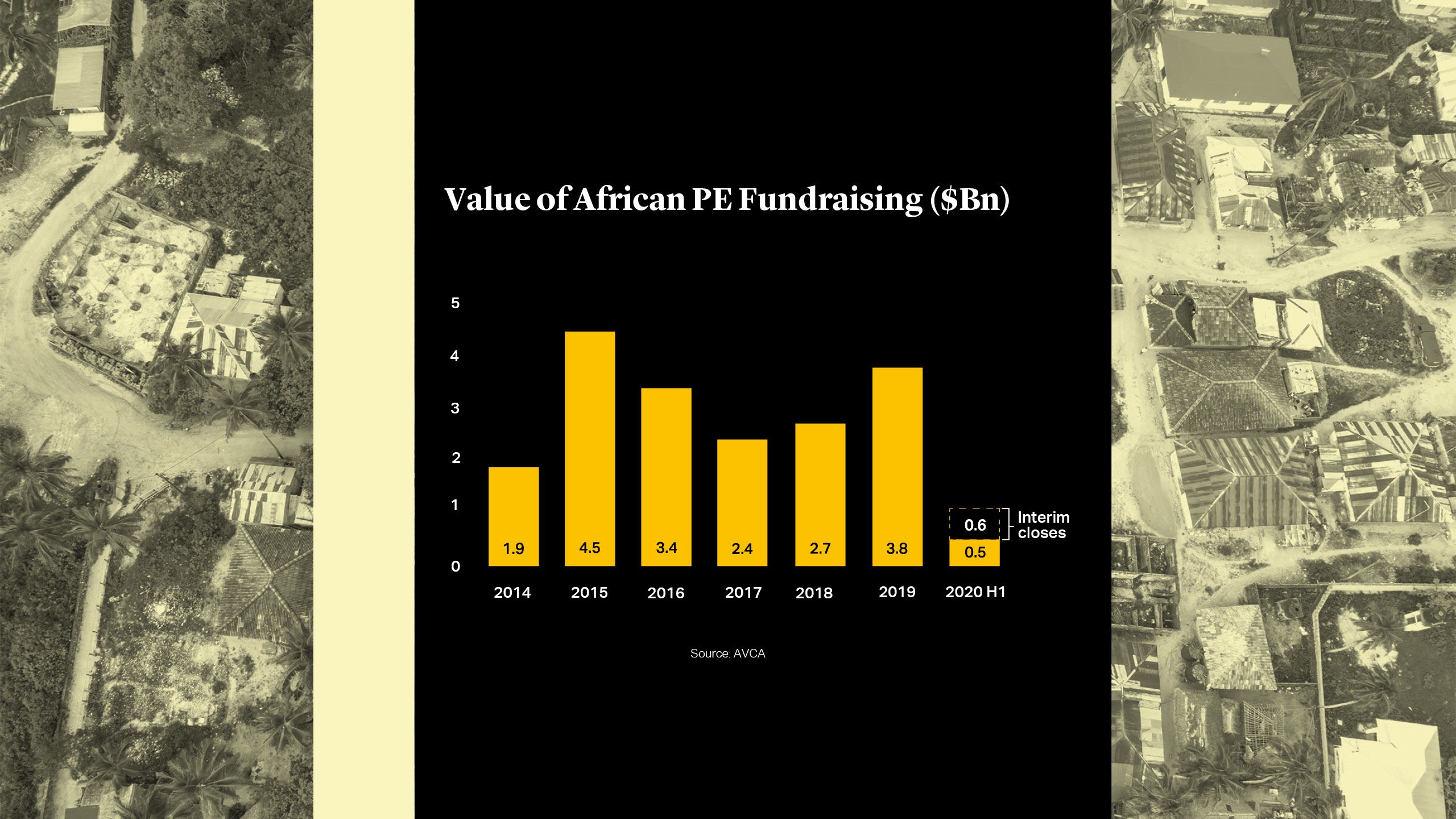

Global private equity firms appear to be struggling to successfully capitalise on “Africa Rising”, the impressive growth and attractive demographics that the continent offers.

Carlyle Group, which raised $700 million to invest in sub-Saharan Africa in 2014, announced last year that it was no longer pursuing an Africa-dedicated buyout fund, marking the latest US-private equity fund to scale back investment on the continent{{1}}{{{Global Buyout Firm Carlyle Group Pulls Back From Africa Source: Wall Street Journal Pro Private Equity}}}.

Carlyle’s move follows that of KKR{{2}}{{{Out of Africa: KKR Disbands African Private-Equity Team</br>Source: Wall Street Journal }}}and Blackstone Group{{3}}{{{ Blackstone Is Pulling Back From Africa</br>Source: Bloomberg}}} – both of which planned to invest heavily in the region but cut back their plans in 2017 and 2019 respectively. After earmarking resources for dedicated Africa strategies, it was reported that these buyout behemoths did not find a pipeline of deals of the size and scale to match their target investment profiles. These high-profile manoeuvers are testament to the challenges facing global PE firms in Africa.

These challenges were further exacerbated in 2020 by the disruptions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. GPs now have an even tougher market to navigate with Sub-Saharan Africa potentially facing its first recession in 25 years, upending any long-term growth assumptions and adding substantial challenges to investing.

But while the crisis has severely hampered industries like tourism and aviation, COVID-19 has provided a catalyst for others. New opportunities are emerging in healthcare, tech, manufacturing and financial services. So how can global PE firms position themselves to take advantage of these opportunities?

Global private equity firms appear to be struggling to successfully capitalise on “Africa Rising”, the impressive growth and attractive demographics that the continent offers.

Carlyle Group, which raised $700 milion to invest in sub-Saharan Africa in 2014, announced last year that it was no longer pursuing an Africa-dedicated buyout fund, marking the latest US-private equity fund to scale back investment on the continent{{1}}{{{Global Buyout Firm Carlyle Group Pulls Back From Africa Source: Wall Street Journal Pro Private Equity}}}.

Carlyle’s move follows that of KKR{{2}}{{{Out of Africa: KKR Disbands African Private-Equity Team</br>Source: Wall Street Journal }}}and Blackstone Group{{3}}{{{ Blackstone Is Pulling Back From Africa</br>Source: Bloomberg}}} – both of which planned to invest heavily in the region but cut back their plans in 2017 and 2019 respectively. After earmarking resources for dedicated Africa strategies, it was reported that these buyout behemoths did not find a pipeline of deals of the size and scale to match their target investment profiles. These high-profile manoeuvers are testament to the challenges facing global PE firms in Africa.

These challenges were further exacerbated in 2020 by the disruptions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. GPs now have an even tougher market to navigate with Sub-Saharan Africa potentially facing its first recession in 25 years, upending any long-term growth assumptions and adding substantial challenges to investing.

But while the crisis has severely hampered industries like tourism and aviation, COVID-19 has provided a catalyst for others. New opportunities are emerging in healthcare, tech, manufacturing and financial services. So how can global PE firms position themselves to take advantage of these opportunities?

Finding Scalable Businesses

Ticket size remains a major challenge for global PE firms in Africa. The average global PE transaction in 2019 was $157mn according to McKinsey{{4}}{{{ A new decade for private markets: McKinsey Global Private Markets Review 2020 Source: Mckinsey}}}, but in Africa most deals are below $50mn{{5}}{{{Private Equity and Venture Capital in Africa: Covid-19 Response Report – Oxford Business Group and AVCA, November 2020 </br>Source: AVCA}}} with the average deal size reported to be $6mn-$8mn in 2018, according to AVCA. Small scale and early stage businesses form a disproportionate percentage of the potential market, and the level of diligence and resources required to successfully deploy capital is often not commensurate with the ticket-size.

A number of investors have, however, remained active by adopting creative deal origination strategies to navigate the challenge of scale. These include specialist African PE players, social impact and growth funds and DFIs. One way they have dealt with the challenge is to adopt a buy and build strategy – rolling up smaller acquisition opportunities as part of a platform play, in sectors such as healthcare, education and telecoms. As well as creating management efficiencies and other synergies, such scaled-up platforms often create better opportunities for future exit. In the education sector, Actis’s pan-African Honoris United Universities education platform provides a good example. The $275mn platform was launched in 2017, and now comprises universities across seven countries in North, South and West Africa, with the latest being the acquisition of Nile University in Nigeria last year.

In the healthcare sector, the Evercare Group is a successful example of the platform play. The Evercare Group is an integrated healthcare delivery platform with 29 hospitals, 16 clinics, more than 60 diagnostics centres across Africa and South East Asia. Evercare is wholly owned by the Evercare Health Funds, a US $1bn emerging markets healthcare fund managed by The Rise Funds (the impact investment platform of TPG). Also in the healthcare sector, in November 2020 DPI, CDC and the EBRD committed a combined $750mn to found a pan-African biopharmaceutical platform{{6}}{{{DPI and CDC partner to create $750mn biopharmaceutical platform to broaden access of vital specialty generic drugs across Africa Source: AVCA}}}.

As an alternative to deploying the buy and build strategy, other global sponsors have found scale by focusing on established pan-African businesses. In October 2018, Warburg Pincus led a consortium of investors including Temasek, Singtel and SoftBank Group to purchase a $1.25bn stake in Airtel Africa, a telecoms operator with operations across 14 countries in Africa. The size and scale of the investment marks it as one of the largest PE investments in Africa.

As the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) takes shape and agreements on trade tariffs are reached, greater opportunities for cross-border business will emerge. COVID-19 could also provide something of a catalytic agent too, forcing a re-think on global supply chains and accelerating local manufacturing and the creation of higher value goods across regions on the continent.

A number of investors have, however, remained active by adopting creative deal origination strategies to navigate the challenge of scale. These include specialist African PE players, social impact and growth funds and DFIs. One way they have dealt with the challenge is to adopt a buy and build strategy - rolling up smaller acquisition opportunities as part of a platform play, in sectors such as healthcare, education and telecoms. As well as creating management efficiencies and other synergies, such scaled-up platforms often create better opportunities for future exit. In the education sector, Actis’s pan-African Honoris United Universities education platform provides a good example. The $275mn platform was launched in 2017, and now comprises universities across seven countries in North, South and West Africa, with the latest being the acquisition of Nile University in Nigeria last year.

In the healthcare sector, the Evercare Group is a successful example of the platform play. The Evercare Group is an integrated healthcare delivery platform with 29 hospitals, 16 clinics, more than 60 diagnostics centres across Africa and South East Asia. Evercare is wholly owned by the Evercare Health Funds, a US $1bn emerging markets healthcare fund managed by The Rise Funds (the impact investment platform of TPG). Also in the healthcare sector, in November 2020 DPI, CDC and the EBRD committed a combined $750mn to found a pan-African biopharmaceutical platform{{6}}{{{DPI and CDC partner to create $750 million biopharmaceutical platform to broaden access of vital specialty generic drugs across Africa Source: AVCA}}}.

As an alternative to deploying the buy and build strategy, other global sponsors have found scale by focusing on established pan-African businesses. In October 2018, Warburg Pincus led a consortium of investors including Temasek, Singtel and SoftBank Group to purchase a $1.25bn stake in Airtel Africa, a telecoms operator with operations across 14 countries in Africa. The size and scale of the investment marks it as one of the largest PE investments in Africa.

As the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) takes shape and agreements on trade tariffs are reached, greater opportunities for cross-border business will emerge. COVID-19 could also provide something of a catalytic agent too, forcing a re-think on global supply chains and accelerating local manufacturing and the creation of higher value goods across regions on the continent.

Backing the Right Founders

Most PE activity in Africa is through growth capital or minority investment, meaning that GPs often become minority partners in founder-led or family-run businesses. Founders and families may have strong views on how their businesses – that they started or grew up with – should be run, and operational change (including management shake-ups) may not be welcome. Sensitivity in navigating such issues is often one of the most important skillsets for investors to bring to the table, and can often make the difference between landing the deal and missing out.

The recently reported face-off between Alta Semper (a London based PE firm focused on investments in Africa) and the founder of Health Plus in Nigeria, is a reminder of the importance of alignment between the PE fund and its partner. Alta Semper made an investment in Health Plus in 2018, but disagreements between the founder-CEO and Alta Semper relating to the management of the Company saw the parties ending up in litigation in October 2020.

Focusing on businesses that have already received VC funding or other external investor financing, and so who may have some degree of management and operational support in place (e.g., finance and compliance functions), may help to avoid some of these points of friction. But in dealing with founders and families who are receiving their first institutional funding, a shared vision, trust and a spirit of true partnership are critical to implementing any operational changes or growth plans. Drafting clear legal agreements can only take the parties so far: building these relationships can take time but are critical.

Global or deal specific partnerships with local GPs who have deep local roots and strong relationships may help to bridge this gap. In some cases, actual consolidation with local players may be a viable option. Cerberus, for example, acquired SGI Frontier Capital in 2018, a regional private equity firm focused on investments in Ethiopia and some other emerging economies.

Backing the Right Founders

Most PE activity in Africa is through growth capital or minority investment, meaning that GPs often become minority partners in founder-led or family-run businesses. Founders and families may have strong views on how their businesses – that they started or grew up with – should be run, and operational change (including management shake-ups) may not be welcome. Sensitivity in navigating such issues is often one of the most important skillsets for investors to bring to the table, and can often make the difference between landing the deal and missing out.

The recently reported face-off between Alta Semper (a London based PE firm focused on investments in Africa) and the founder of Health Plus in Nigeria, is a reminder of the importance of alignment between the PE fund and its partner. Alta Semper made an investment in Health Plus in 2018, but disagreements between the founder-CEO and Alta Semper relating to the management of the Company saw the parties ending up in litigation in October 2020.

Focusing on businesses that have already received VC funding or other external investor financing, and so who may have some degree of management and operational support in place (e.g., finance and compliance functions), may help to avoid some of these points of friction. But in dealing with founders and families who are receiving their first institutional funding, a shared vision, trust and a spirit of true partnership are critical to implementing any operational changes or growth plans. Drafting clear legal agreements can only take the parties so far: building these relationships can take time but are critical.

Global or deal specific partnerships with local GPs who have deep local roots and strong relationships may help to bridge this gap. In some cases, actual consolidation with local players may be a viable option. Cerberus, for example, acquired SGI Frontier Capital in 2018, a regional private equity firm focused on investments in Ethiopia and some other emerging economies.

Managing FX Risk

Currency volatility is always a concern for investments in Africa. Many of the largest African economies with a high dependence on commodity exports and those with burgeoning public debts have experienced significant currency depreciation against the US dollar over the last decade. Restrictions on foreign exchange movements and the existence of multiple or unofficial exchange markets are still rife across the continent, with the potential to further destabilise domestic currencies. Although depreciation assumptions will typically be priced into private equity valuations, the effect of sudden currency devaluations on expected returns could be significant.

Apart from the risk of currency depreciation, the lack of availability of US dollars (or other freely tradable currency) in the local economy may further impact the repatriation of capital. Obtaining appropriate regulatory approvals at the time of the investment to enable capital repatriation is a key consideration for investment structuring, but may not guarantee the repatriation of capital when required.

The availability of hedging instruments across the continent tends to be limited, and these products are often not well suited to the needs of PE firms, given the long dated nature of the currency exposure. Even where hedging instruments are available, they are often expensive compared with usual benchmark pricing and inadequate in scope.

The ideal investment to manage FX exposure will involve a target that generates dollar revenues or operates in a quasi-dollar environment. Some companies may also have a natural hedge against currency movements through a portfolio of assets with income and exposure across a basket of currencies. The ability to pass on currency risks to consumers may also be a feature of some business models. Other techniques for managing FX risks include the use of a structured investment through a dollar denominated instrument – such as a convertible debt or a loan note. This will effectively push the currency risk to the founders or the target and may provide a fixed dollar return for the investor over the term of the instrument. Happily these are not issues for investments in the West Africa franc countries that have their currency pegged against the Euro.

Permanent capital vehicles can also offer advantages over funds with set investment timelines. Without the pressure to exit, GPs can wait out periods of currency volatility and realise the value of investments in other ways.

Managing FX Risk

Currency volatility is always a concern for investments in Africa. Many of the largest African economies with a high dependence on commodity exports and those with burgeoning public debts have experienced significant currency depreciation against the US dollar over the last decade. Restrictions on foreign exchange movements and the existence of multiple or unofficial exchange markets are still rife across the continent, with the potential to further destabilise domestic currencies. Although depreciation assumptions will typically be priced into private equity valuations, the effect of sudden currency devaluations on expected returns could be significant.

Apart from the risk of currency depreciation, the lack of availability of US dollars (or other freely tradable currency) in the local economy may further impact the repatriation of capital. Obtaining appropriate regulatory approvals at the time of the investment to enable capital repatriation is a key consideration for investment structuring, but may not guarantee the repatriation of capital when required.

The availability of hedging instruments across the continent tends to be limited, and these products are often not well suited to the needs of PE firms, given the long dated nature of the currency exposure. Even where hedging instruments are available, they are often expensive compared with usual benchmark pricing and inadequate in scope.

The ideal investment to manage FX exposure will involve a target that generates dollar revenues or operates in a quasi-dollar environment. Some companies may also have a natural hedge against currency movements through a portfolio of assets with income and exposure across a basket of currencies. The ability to pass on currency risks to consumers may also be a feature of some business models. Other techniques for managing FX risks include the use of a structured investment through a dollar denominated instrument – such as a convertible debt or a loan note. This will effectively push the currency risk to the founders or the target and may provide a fixed dollar return for the investor over the term of the instrument. Happily these are not issues for investments in the West Africa franc countries that have their currency pegged against the Euro.

Permanent capital vehicles can also offer advantages over funds with set investment timelines. Without the pressure to exit, GPs can wait out periods of currency volatility and realise the value of investments in other ways.

Options for Exit

Limited exit options in Africa’s relatively illiquid domestic markets remain one of the biggest challenges for PE firms. Initial public offerings remain rare, and sales to trade buyers or other PE firms and DFIs are the most common routes.

The news on this front is not all gloomy. Some notable exits in recent years point to an improved outlook, while AVCA reported an emerging trend of management buyouts and private sales in 2019{{7}}{{{Private Equity and Venture Capital in Africa: Covid-19 Response Report – Oxford Business Group and AVCA, November 2020 Source: AVCA}}}. American Towers acquired mobile tower company Eaton Towers for $1.85bn in January 2020, while in Cote d’Ivoire, ECP was able to partially exit its investment in pan-African bank Oragroup through a public offering on the BRVM in 2019. Helios also successfully listed its Helios Towers business on the London Stock Exchange in 2019, and in the same year Airtel Africa was also listed in London.

Tech and tech-enabled businesses may have a greater variety of options for exits. Many are developing solutions such as payments services which can be attractive add-ons for corporates or banks. In October 2020, for example, American financial services company Stripe acquired Lagos-based payments provider Paystack.

Options for Exit

Limited exit options in Africa’s relatively illiquid domestic markets remain one of the biggest challenges for PE firms. Initial public offerings remain rare, and sales to trade buyers or other PE firms and DFIs are the most common routes.

The news on this front is not all gloomy. Some notable exits in recent years point to an improved outlook, while AVCA reported an emerging trend of management buyouts and private sales in 2019{{7}}{{{Private Equity and Venture Capital in Africa: Covid-19 Response Report – Oxford Business Group and AVCA, November 2020 </br>Source: AVCA}}}. American Towers acquired mobile tower company Eaton Towers for $1.85bn in January 2020, while in Cote d’Ivoire, ECP was able to partially exit its investment in pan-African bank Oragroup through a public offering on the BRVM in 2019. Helios also successfully listed its Helios Towers business on the London Stock Exchange in 2019, and in the same year Airtel Africa was also listed in London.

Tech and tech-enabled businesses may have a greater variety of options for exits. Many are developing solutions such as payments services which can be attractive add-ons for corporates or banks. In October 2020, for example, American financial services company Stripe acquired Lagos-based payments provider Paystack.

Michael J. Preston

Partner

London

T: +44 20 7614 2255

mpreston@cgsh.com

V-Card

Barthélemy Faye

Partner