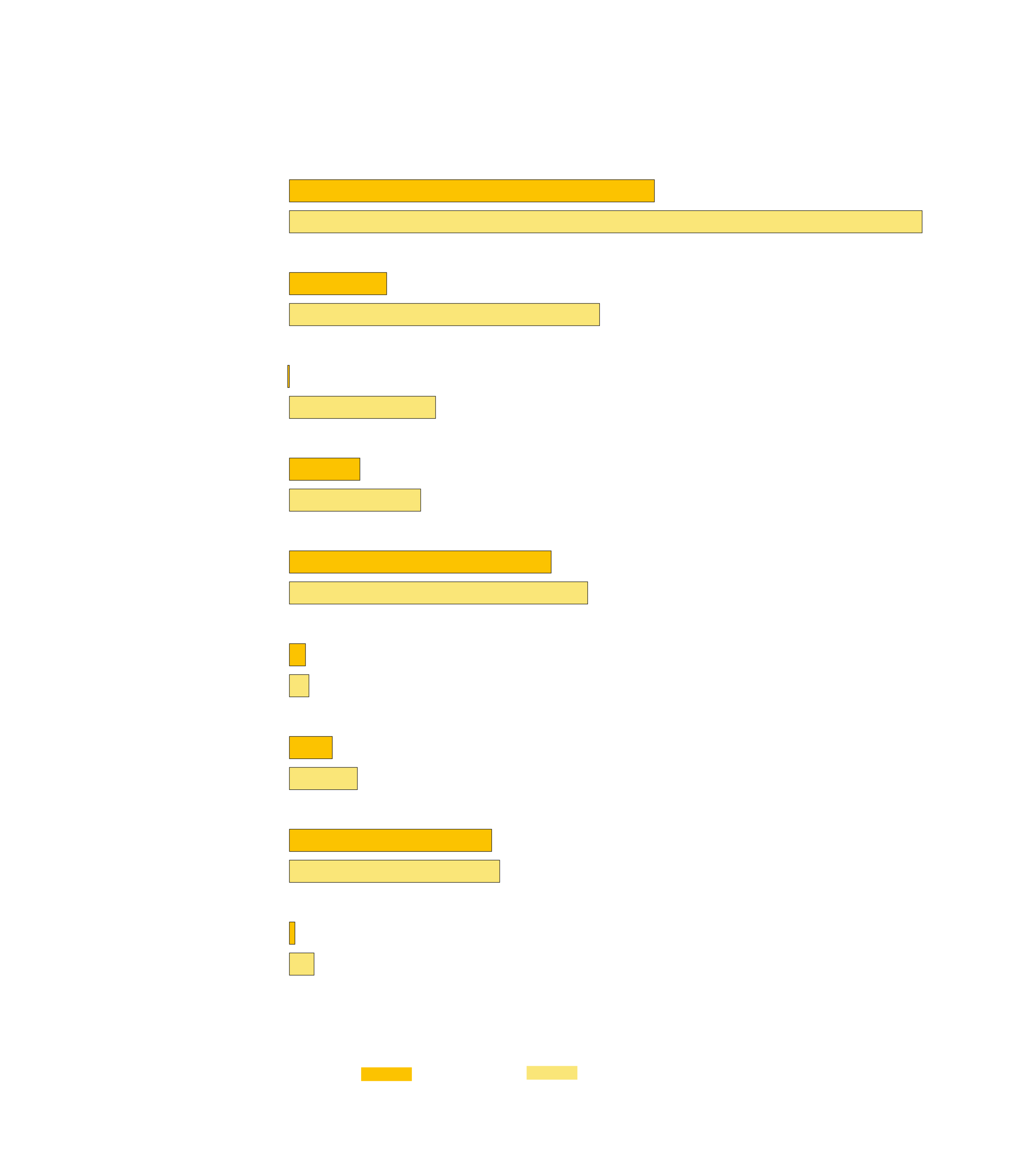

While Africa was already one of the lowest recipients of foreign direct investment (FDI) globally, inbound investment to African countries was further hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. FDI flows to the continent were down 18% to $38 billion last year according to UNCTAD, while developing Asia attracted $476 billion (down 4%) in 2020 and Latin America and the Caribbean took $101 billion (down 37%)1. Restrictions on foreign ownership, political risk, ambiguity of legal systems, and challenging logistics have historically kept foreign investment from the African continent.

Now, pandemic-related risks, the pace of vaccination roll-out programmes and the damaging cost of economic support packages have added new challenges that investors and governments must grapple with. However, a growing trend towards privatisation, which has gathered pace across a number of African nations, may be a catalyst for increased FDI flows into the continent.

While Africa was already one of the lowest recipients of foreign direct investment (FDI) globally, inbound investment to African countries was further hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. FDI flows to the continent were down 18% to $38 billion last year according to UNCTAD, while developing Asia attracted $476 billion (down 4%) in 2020 and Latin America and the Caribbean took $101 billion (down 37%)1. Restrictions on foreign ownership, political risk, ambiguity of legal systems, and challenging logistics have historically kept foreign investment from the African continent.

Now, pandemic-related risks, the pace of vaccination roll-out programmes and the damaging cost of economic support packages have added new challenges that investors and governments must grapple with. However, a growing trend towards privatisation, which has gathered pace across a number of African nations, may be a catalyst for increased FDI flows into the continent.

Why Privatise?

For governments sitting on prized and profitable state-run companies, monetising these assets through privatisation can provide a valuable source of revenues at a time when other capital seems scarce, as well as bringing a range of other benefits.

When properly done, privatisation can enhance economic efficiency by improving performance, decrease the need for government intervention while increasing revenue, and introduce competition (and thereby innovation) in monopolised sectors2.

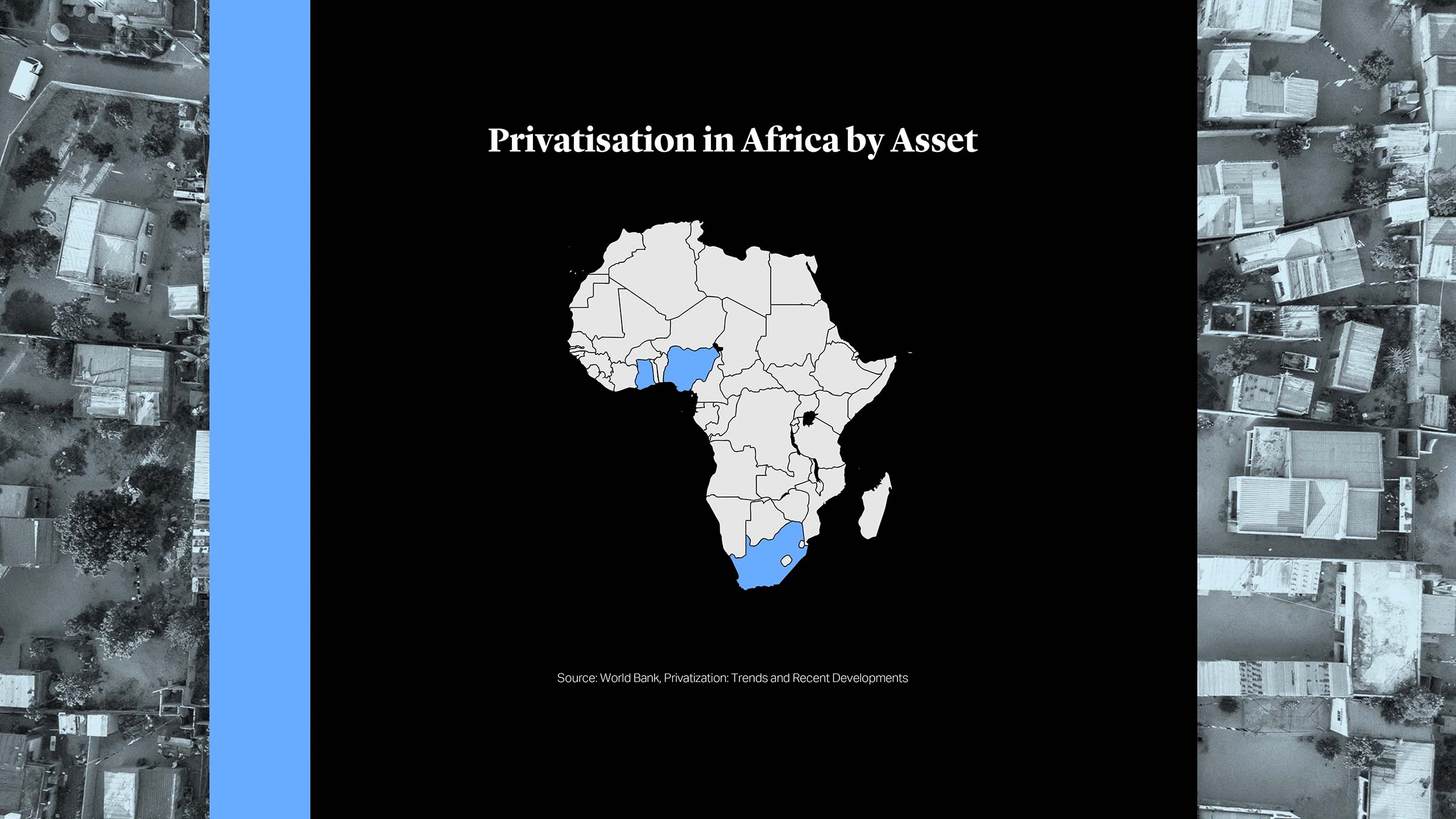

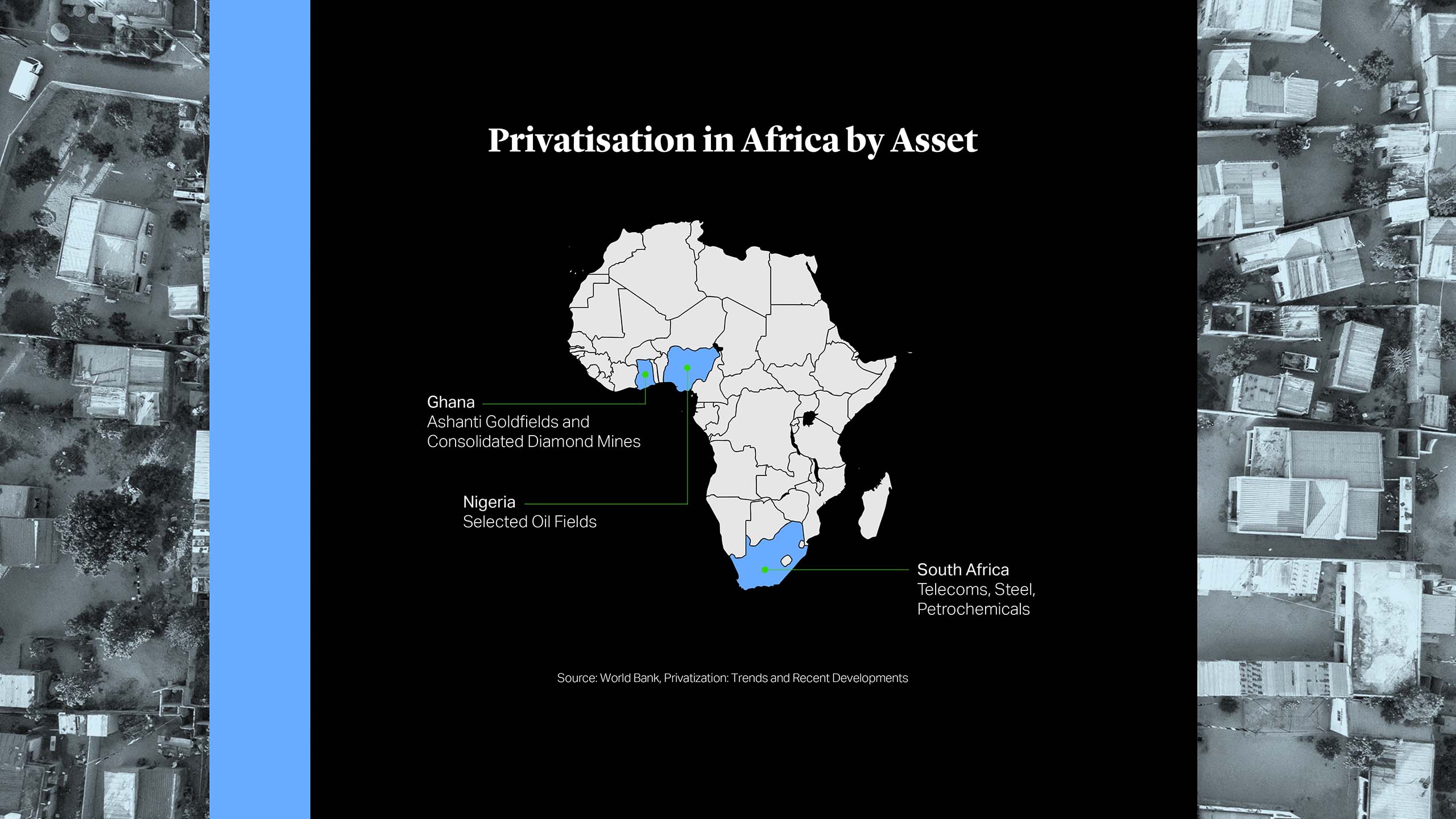

Privatisation first came to the continent much later than in Europe. Between 1990 and 2003, sub-Saharan African governments raised $11 billion through privatisation, though the majority of the 960 transactions were for small, low-value firms in competitive sectors. The bulk of the transactions came from Ghana, South Africa, and Nigeria3.

Much of the privatisation movement was driven by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Financing from the IMF had conditions attached, which encouraged countries to decrease government intervention in the economy, introduce competitiveness, reduce market monopolies, and increase efficiency.

Ultimately, however, many of these privatisations failed, and the businesses were taken back into state ownership. A lack of clear political will to privatise, plus a lack of understanding of the process, contributed to a series of problems and reversals. At the heart of the issue was the fact that many businesses simply weren’t commercially viable and could not survive in a competitive marketplace without state support.

Encouragingly, it is now governments rather than the IMF and the World Bank that are driving the privatisation agenda. Egypt, Ethiopia, and Angola are examples of African countries that have all launched large-scale privatisation programmes in the last few years. These new attitudes bring new, and exciting, opportunities.

Lessons From the Past

When poorly managed, privatisation programmes can have a catastrophic impact on a country’s finances. Nigeria spent almost a decade struggling to sell state-owned telecom company NITEL before eventually opting to wind up operations in November 2014. At the point of sale, NITEL owed creditors ₦400 billion naira ($2.5 billion).

A look at Nigeria’s attempt to privatise Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN) also highlights some of the issues and challenges such complex transactions can face.

The unbundling of PHCN, which began in 2011, saw the company split into pieces, with 11 distribution companies and 6 generating companies sold to different private buyers. Transmission Company of Nigeria (TCN) was the surviving piece of PHCN that remained in state ownership, with the government retaining the operation of the transmission assets.

The privatisation of PHCN was expected to generate huge investment in the power sector and turbo-charge Nigeria’s economy. But a catalogue of errors from unreliable audit accounts – which failed to reveal that the running costs of the distribution companies largely exceeded revenues – to limited warranty protection and no government support, left investors facing vast losses.

The ill-treatment of private investors by the Nigerian authorities culminated in heavy-handed regulatory intervention, when Lagos disregarded the privatisation process that had been put in place and announced new rules under which the privatised market would operate.

Against this backdrop, appetite for investment – and trust in the political process – will be tested by Nigeria’s plans to sell five power generating companies constructed under the National Integrated Power Project (NIPP).

The history of the PHCN privatisation underlines the need for high levels of transparency to ensure that investors are able to make informed decisions. Companies earmarked for sale should be trading successfully without reliance on government support, and should already be providing a high level of disclosure to the market, such as quarterly financial reports conforming to best practice standards. Companies which are already partially listed, or which have recently prepared documentation to raise debt, may be a good bet.

Sell or Float?

The most common routes to monetising state assets are via strategic stake sales to one or two investors or by listing shares in the public markets.

Strategic sales are historically more common than public listings. Strategic sales can be more straightforward, offer greater certainty on pricing and are perceived to be the best route to improved efficiency, though they are also often politically unpopular. In Egypt, the government started a privatisation program in the 1990s through the strategic sale of assets, a move that proved unpopular among the public and was subject to challenge in the courts on several grounds, including irregularities in the bidding process and lack of transparency. A number of these privatisations were later annulled by court orders. Earlier this year, a World Bank-backed water bill to promote public-private partnerships for investments in the delivery of water services and the development and management of water resources infrastructure was met with fury by civil society groups and trade unions in Nigeria over concerns that it commercialised access to water. Part of the opposition to the bill is that it does not provide for an opportunity for citizens to participate in the process. Similar sentiments on local participation often drive public opposition to strategic sales which may be less pronounced with a public listing.

As local stock exchanges are gradually becoming more sophisticated and are facilitating stock holding and trading by foreign investors, a public floatation of state companies is becoming an increasingly viable – and popular – alternative to strategic stake sales. Though more exposed to global market volatility and other external factors, divesting state-owned assets through initial or secondary public offering of shares on the stock market can deepen local capital markets and, given the involvement of international institutional investors, raise corporate governance standards through a series of checks and balances brought by international investment standards. A partial divestment of state-owned assets after floating on the stock market is also likely to trigger less political opposition than a complete divestment through a bilateral sale would typically do.

Sell or Float?

The most common routes to monetising state assets are via strategic stake sales to one or two investors or by listing shares in the public markets.

Strategic sales are historically more common than public listings. Strategic sales can be more straightforward, offer greater certainty on pricing and are perceived to be the best route to improved efficiency, though they are also often politically unpopular. In Egypt, the government started a privatisation program in the 1990s through the strategic sale of assets, a move that proved unpopular among the public and was subject to challenge in the courts on several grounds, including irregularities in the bidding process and lack of transparency. A number of these privatisations were later annulled by court orders. Earlier this year, a World Bank-backed water bill to promote public-private partnerships for investments in the delivery of water services and the development and management of water resources infrastructure was met with fury by civil society groups and trade unions in Nigeria over concerns that it commercialised access to water. Part of the opposition to the bill is that it does not provide for an opportunity for citizens to participate in the process. Similar sentiments on local participation often drive public opposition to strategic sales which may be less pronounced with a public listing.

As local stock exchanges are gradually becoming more sophisticated and are facilitating stock holding and trading by foreign investors, a public floatation of state companies is becoming an increasingly viable – and popular – alternative to strategic stake sales. Though more exposed to global market volatility and other external factors, divesting state-owned assets through initial or secondary public offering of shares on the stock market can deepen local capital markets and, given the involvement of international institutional investors, raise corporate governance standards through a series of checks and balances brought by international investment standards. A partial divestment of state-owned assets after floating on the stock market is also likely to trigger less political opposition than a complete divestment through a bilateral sale would typically do.

Egypt’s IPO Route

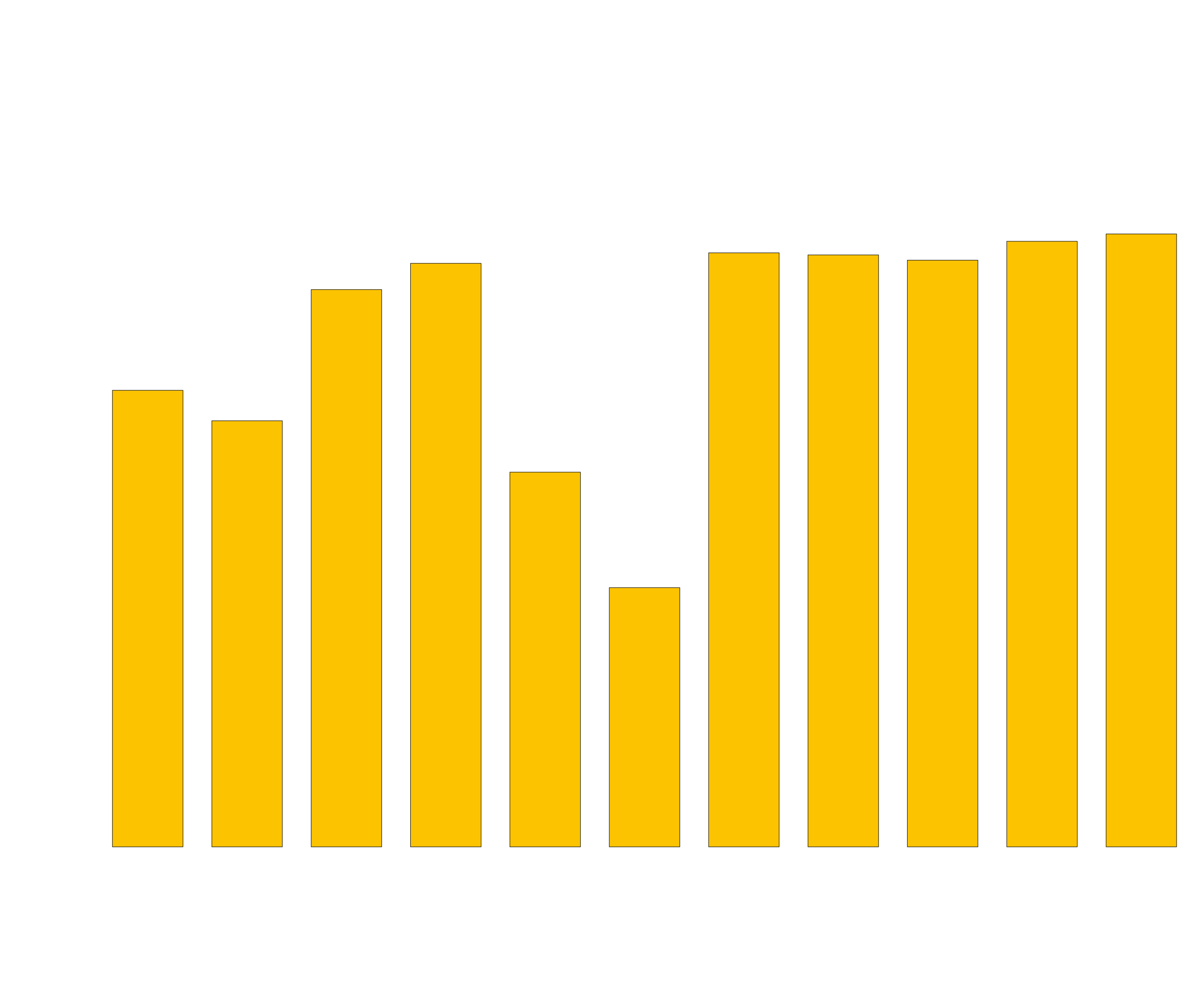

Egypt offers a good example of one of the more recent privatisation programmes that has embraced the public markets route. In 2016 Egypt embarked on an ambitious programme to privatise 23 state-owned companies, in a bid to transform its tightly controlled economy, boost public finances and bring more investors to Cairo. The privatisations would be implemented via initial or secondary public offerings, enabling the state to maintain a controlling stake but simultaneously deepen its nascent equity markets.

While progress has been slow – with only a 4.5% stake in tobacco producer Eastern Company4 sold in March 2019 – returning market stability is expected to prompt a slew of deals. Banque du Caire, which shelved a $500 million dual-listing in London and Cairo last year when COVID-19 hit, is expected to re-launch its IPO5 while state-owned e-payments firm e-Finance is likely to pull the trigger in the second half of the year6.

For investors, Egypt’s IPO programme offers the chance to buy into one of the MENA region’s fastest growing economies. Egypt’s economy proved resilient though the pandemic, growing 2% between October and December 2020, with the government targeting 5.4% growth for the fiscal year 2021/22.

Outlook

African countries continue to battle difficult macro-economic conditions and strive to attract private investment to fuel the ongoing economic transformation, but regulatory and other challenges continue to affect the prospects for successful privatisation programmes, underscored by the recent experiences of Angola and Ethopia:

- Angola has named 195 assets for privatisation to kick-start its lacklustre economy, including the earmarking of stakes for sale in oil company Sonangol (in 2022) and Banco BAI, the country’s biggest private lender by assets. But private investors remain reticent to engage as the country looks to shed an image of widespread corruption and unfriendliness to foreign capital. Angola ranks 142nd out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s annual Corruption Perceptions Index, a backdrop that potential investors will ponder7.

- Ethiopia’s attempts to partially privatise Ethio Telecom are ongoing. A consortium led by Kenya’s Safaricom, Vodafone and Japan’s Sumitomo was granted a licence for their $850mn bid in May 2021, though a smaller bid by MTN fell through8.

Successful privatisations need a robust regulatory environment which supports the needs and rights of private investors and encourages high levels of disclosure. Investing alongside multilaterals, export credit agencies, development finance institutions and insurers may help investors mitigate risks.

Barthélemy Faye

Partner

Paris

T: +33 1 40 74 68 00

bfaye@cgsh.com

V-Card

Michael J. Preston

Partner

London

T: +44 20 7614 2255

mpreston@cgsh.com

V-Card

Mohamed Taha

Associate