African states’ economies are frequently driven by their natural resources sectors: oil and gas in Nigeria and Angola, iron ore in Mauritania, and copper in Uganda and Zambia1. Indeed, oil, gas, and mineral resources already account for more than 75% of Africa’s exports and the ongoing negotiation of large-scale trade agreements is likely to further boost Africa’s natural resources sector2.

The vast supply of energy and natural resources available on the continent represents huge wealth potential for further economic development3.

The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), which came into force on 1 January 2021, is expected to provide a significant impetus to Africa’s natural resources sector, among other areas. The AfCFTA establishes a single market covering trade and investment for almost all African states, thereby representing a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion4. The reduction in tariffs and non-trade barriers brought about by the AfCFTA is anticipated to vitalise Africa’s energy and natural resources sector5.

Against this backdrop of immense economic opportunity, it seems inevitable that cross-border disputes involving foreign investors operating in African states’ energy and natural resources will arise6. In practice, affected stakeholders often turn to international arbitration as a means to resolve such disputes, facilitated by the rapid growth witnessed in the African arbitration landscape in recent years7.

Moreover, as unexploited reserves of natural resources become scarcer and new issues arise in relation to the energy and natural resources sector, certain trends can be identified in disputes implicating African states’ interests and involvement in their respective natural resources sectors.

African states’ economies are frequently driven by their natural resources sectors: oil and gas in Nigeria and Angola, iron ore in Mauritania, and copper in Uganda and Zambia1. Indeed, oil, gas, and mineral resources already account for more than 75% of Africa’s exports and the ongoing negotiation of large-scale trade agreements is likely to further boost Africa’s natural resources sector2.

The vast supply of energy and natural resources available on the continent represents huge wealth potential for further economic development3.

The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), which came into force on 1 January 2021, is expected to provide a significant impetus to Africa’s natural resources sector, among other areas. The AfCFTA establishes a single market covering trade and investment for almost all African states, thereby representing a combined GDP of $3.4 trillion4. The reduction in tariffs and non-trade barriers brought about by the AfCFTA is anticipated to vitalise Africa’s energy and natural resources sector5.

Against this backdrop of immense economic opportunity, it seems inevitable that cross-border disputes involving foreign investors operating in African states’ energy and natural resources will arise6. In practice, affected stakeholders often turn to international arbitration as a means to resolve such disputes, facilitated by the rapid growth witnessed in the African arbitration landscape in recent years7.

Moreover, as unexploited reserves of natural resources become scarcer and new issues arise in relation to the energy and natural resources sector, certain trends can be identified in disputes implicating African states’ interests and involvement in their respective natural resources sectors.

Factors Specific to Energy and Natural Resources Disputes

Due to the economic value of the underlying resources, the stakes are often very high in energy and natural resources disputes, with billions of dollars potentially at stake8. For instance, on 7 June 2021, mining company Avima Iron Ore Limited announced it was launching arbitration proceedings against the Republic of the Congo for the revocation of an iron ore license, through which it would be seeking $27 billion in damages9. Such high stakes require an effective and reliable mechanism of resolving disputes, which international arbitration can provide.

As energy and natural resources assets in Africa are commonly managed or partly owned by governments or state-affiliated entities, and infrastructure and assets are often impacted by national legislative and tax initiatives, disputes often arise between host states and foreign investors. Such disputes are frequently resolved through investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms, whether contractual or with the support of bilateral investment treaties.

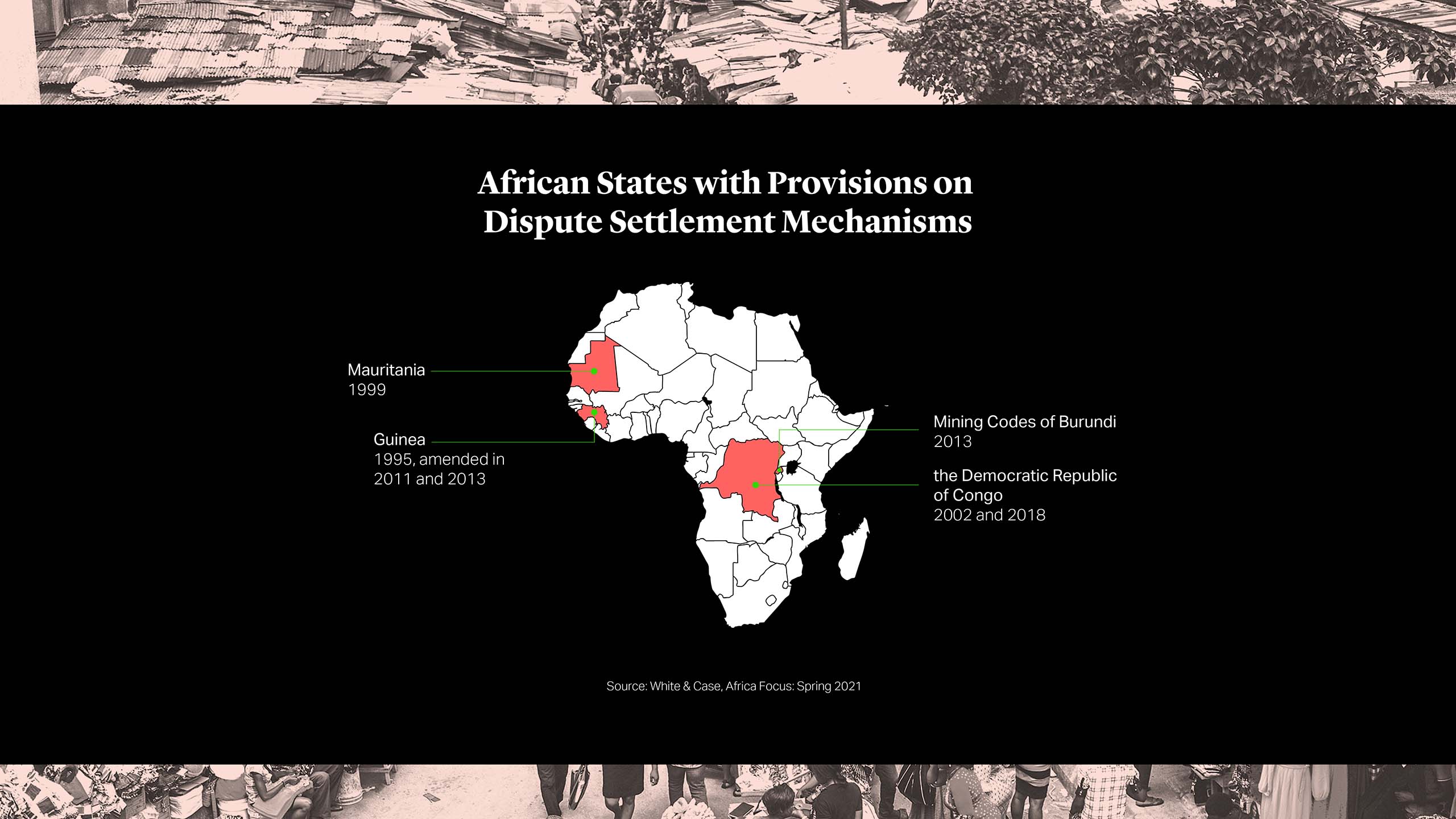

In addition, some African states have also passed legislation on foreign investment or have enacted mining or other sector-specific codes with some provisions on dispute settlement mechanisms.

Recent Trends in Energy and Natural Resources Disputes

In recent years, the African continent has become a thriving hub for investments in the energy and natural resources sector. As a result, several African states have passed legislation enabling the host country to require a minimum level of domestic ownership in foreign investor-led projects. For instance, Uganda’s cabinet has recently approved a draft mining law which allows the government to own shares in private mining operations10 .

In a similar vein, Tanzania has taken a series of measures aimed at modifying the legal framework for foreign investors operating in the country’s energy and natural resources sector. Tanzania has notably terminated some of its existing bilateral investment treaties, and has effectively prohibited recourse to international arbitration as a dispute resolution mechanism for energy and natural resources disputes11.

In reaction to such measures, in 2019 a claim brought by Canadian gold mining company Barrick Gold against Tanzania in the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) culminated in a settlement agreement creating a new Tanzanian entity, in which the government would hold a 16% stake12. This essentially allowed Tanzania to share the cash flow generated by the mines, with the government’s stake bolstered by a favourable domestic tax regime.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that price volatility constitutes an inherent risk for investors operating in the energy and natural resources sector in the long term. Investments in natural resources are also vulnerable to shifting political dynamics, and global economic fluctuations can have a massive impact on the profitability of projects conducted in this sector.

Political and economic instability, along with the intrinsic difficulty of extraction processes, can often lead to project delays, increasing the risk profile of the sector. The COVID-19 global pandemic has further impacted the energy and natural resources sector in Africa, as players and foreign investors operating in this sector are now confronted with a less predictable business environment.

In parallel, international and domestic sustainability initiatives have increased demand for renewable energy sources. Such initiatives are expected to create added pressure on African states’ energy and natural resources sectors to adapt and face the consequences of a potentially declining demand in traditional oil and gas production.

The global move towards renewable and more sustainable energy sources is expected to lead to a surge in cross-border disputes and an increase in environmental claims, for example, as states seek to meet their sustainability commitments by updating the terms of longstanding licenses13. Disputes may also arise based on a failure by companies engaged in extractive activities to obtain a “social license”, a term use to describe acceptance of a company’s activities by the local community14.

Looking Forward

As African nations adapt to the shifting nature of investments in the energy and natural resources sector, new instruments such as the AfCFTA are expected to provide a clear framework for foreign investors, potentially reducing the unpredictability often associated with the establishment of large-scale projects in unstable economies.

In particular, the AfCFTA’s upcoming Investment Protocol is expected to set out investment protection provisions, which will create a more structured legal framework for the protection of the rights of foreign investors, to supplement the legal and contractual framework15. As a consequence, the risk associated with the establishment and operation of investments in Africa’s energy and natural resources sector is likely to be reduced16, streamlining the procedure for resolution of international disputes, while creating space for the sector to further expand.

Christopher P. Moore

Partner

London

T: +44 20 7614 2227

New York

T: +1 212 225 2836

cmoore@cgsh.com

V-Card

Laurie Achtouk‑Spivak

Counsel

Paris

T: +33 3 40 74 68 00

lachtoukspivak@cgsh.com

V-Card

Naomi Tarawali

Associate