United States

There are currently no digital-specific competition laws in the US. Two pieces of pending legislation could change that: the American Innovation and Choice Online Act and the Open App Markets Act. Both bills target so-called “self-preferencing” by large digital platforms. As of January 2024, neither bill has passed. Overall, passage seems unlikely at this stage, but cannot be ruled out.

Authored by Bruce Hoffman, Brian Byrne, Elaine Ewing, George S. Cary, Molly Ma & Alexi T. Stocker

Updated as of January 2024

United States

There are currently no digital-specific competition laws in the US. Two pieces of pending legislation could change that: the American Innovation and Choice Online Act and the Open App Markets Act. Both bills target so-called “self-preferencing” by large digital platforms. As of January 2024, neither bill has passed. Overall, passage seems unlikely at this stage, but cannot be ruled out.

Authored by Bruce Hoffman, Brian Byrne, Elaine Ewing, George S. Cary, Molly Ma & Alexi T. Stocker

Updated as of January 2024

-

1. What rules govern competition in digital markets in the US?

-

There are currently no digital-specific competition laws in the US. Like virtually all firms, digital firms are subject to the Sherman Act (which regulates agreements and single-firm conduct), the Clayton Act (which primarily regulates mergers), the FTC Act (which largely runs in parallel to the other statutes, though may have a slightly broader reach), and similar state laws. In recent times, case law has expanded in ways that are particularly relevant to digital markets. For example, the Supreme Court in Ohio v. American Express held that both sides of a two-sided platform must be taken into account when assessing competitive harm, in certain circumstances.1

However, there are at least two relevant pieces of pending legislation–the American Innovation and Choice Online Act (“AICOA”) and the Open App Markets Act (“OAMA”). If passed, the AICOA and OAMA would introduce sweeping changes to the regulation of competition in digital markets in the US, targeting companies such as Google, Apple, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, and likely TikTok. Various states, including New York, have also considered legislation that would either specifically target digital firms, or would likely have significant effects on them.

-

2. What is the status of any forthcoming digital regulation in the

US?

-

The AICOA and OAMA are currently stalled. In early 2022, drafts of the bills were voted out of committee in a bipartisan manner (through a 16-6 vote and 20-2 vote respectively). However, despite high-profile campaigns calling for a full vote, neither bill was ultimately brought up for one during the last Congress.

Still, passage is possible in this Congress. Since taking office, President Biden has stated that he supports the legislation,2 and in June 2023, the AICOA was reintroduced in the Senate.3 Ultimately, though, passage of either bill is unlikely at this stage. If passed, the AICOA would take effect in one year and the OAMA would take effect in 180 days.

0 daysIF PASSED, THE AICOA WOULD TAKE EFFECT IN ONE YEAR AND OAMA WOULD TAKE EFFECT IN 180 DAYS.Overall, passage either bill seems unlikely at this stage, but cannot be ruled out.

-

3. How are the rules expected to be enforced?

-

If passed, the AICOA and OAMA would be enforceable by the FTC, DOJ, and State Attorneys General. As currently drafted, the OAMA would also create private rights of action for developers.4 All these groups have demonstrated their strong appetite for litigation against large digital platforms. Should either or both bills enter into force, investigations and litigation should be expected.

Injunctive relief would be available under both bills. Further, under the AICOA, enforcers would be able to seek penalties up to 10% of the defendant’s global annual turnover.5 Under the OAMA, app developers could bring private suits for treble damages and State Attorneys General could sue for such damages in the name of developers from their states.6

-

4. Which firms will the rules apply to?

-

If passed, the OAMA would apply to companies that own app stores with over 50 million US users. The OAMA is intended to regulate iOS and the Apple App Store and Google Play and Android. It would also likely cover the Microsoft Store on Windows.

0 millionIF PASSED, THE OAMA WOULD APPLY TO COMPANIES THAT OWN APP STORES WITH OVER 50 MILLION US USERS.The AICOA would apply to a broader set of “covered platforms.” In simple terms, these are online services, owned by large companies, that have a significant number of active users or business users. In practice a significant number of popular products and services supplied by companies like Google, Apple, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, and TikTok will qualify as covered platforms.

Covered platforms under the AICOA are defined using to the following criteria:

- The product or service must be a website, online or mobile app, operating system, digital assistant, or online service.

- The product or service must (1) allow users to generate, share, or interact with content; (2) allow users to perform broad searches; or (3) facilitate offering, selling, shipping, or advertising of goods or services between entities not controlled by the platform.

- The product or service must have at least 50,000,000 US monthly active end users or at least 100,000 US monthly active business users.

- The product or service must be a “critical trading partner” for the sale or provision of any product “offered on or directly related to” the platform. In other words, the product or service could be used either to: (1) restrict or impede access of a business user to its end users; or (2) restrict or impede access of a business user to a tool or service it “needs to effectively serve” its end users.

- The product or service must be at least 25% owned by a company with (1) a market cap greater than USD 550 billion; (2) US revenue greater than USD 550 billion; or (3) greater than 1 billion global monthly active users.

-

5. What are the main substantive rules that would govern firms

covered by the proposed digital regulation?

-

If passed, the AICOA would broadly prohibit covered platforms from self-preferencing, (i.e., preferencing first-party products and services over those of other business users on a covered platform in a manner that materially harms competition).7

The AICOA also contains a number of more specific prohibitions:

- Terms of service discrimination. Covered platforms cannot discriminate among similarly situated business users in the application or enforcement of their terms of service in a manner that materially harms competition.8

- Interoperability. Covered platforms cannot materially restrict or impede business users from interoperating with the same features available to first-party products and services that compete with products or services offered by business users on the covered platform.9

- Tying. Covered platforms cannot condition covered platform access or preferential placement on the use of other first-party products that are not part of or intrinsic to the covered platform.10

- Use of data to compete. Covered platforms cannot use non-public data generated by business users, or their users, to support first-party products that compete against business users on the covered platform.11

- Data access. Covered platforms cannot materially impede business users from accessing data generated on the platform by them or their customers’ interactions with them.12

- Defaults and uninstallation. Covered platforms cannot impede platform users from uninstalling preinstalled software or changing default settings that steer users to first-party products.13

- User interface. Covered platforms cannot treat first-party products more favorably than those of other business users within any platform user interface, including search or ranking functionality.14

- Retaliation. Covered platforms cannot retaliate against users that raise good faith concerns with law enforcement about legal violations.15

The OAMA contains a number of prohibitions specific to covered app stores and operating systems, some of which mirror the AICOA:

- Obligatory first-party payment systems. Covered companies cannot condition use of their app stores or operating systems on use of first-party in-app payment systems.

- Most-favored nation clauses. Covered companies cannot employ most-favored nation clauses in app store terms of service, i.e.,covered app stores could not prohibit developers from offering better terms to users on rival app stores.

- Anti-steering provisions. Covered companies cannot discriminate against developers that offer different terms of sale for use of third-party payment systems or app stores and cannot restrict developers from communicating legitimate business offers.

- Use of data to compete. Covered companies cannot use non-public data from third-party apps to compete against them.16 This provision is narrower in scope than the AICOA’s equivalent prohibition, which prohibits the use of such data entirely in any first-party app that generally competes on the covered platform.

- Defaults. Covered companies must provide “readily accessible means” for operating system users to choose third-party apps and app stores as defaults.17 This provision does not prevent covered companies from setting first-party apps as default. For example, unlike the EU Digital Markets Act, the OAMA does not contain an express requirement to show users default choice screens.

- “Sideloading.” Covered companies must provide “readily accessible” for operating system users to install third-party apps and app stores outside of the covered companies’ first-party app stores. (i.e., must enable “sideloading”).18

- Self-preferencing. Covered companies cannot unreasonably preference first-party or business partners’ apps in their app stores.19

- Interoperability. Covered companies must provide developers access to the same operating system features that are available to first-party products and services, as well as to those that are available to business partners.20

-

6. Are there specific rules governing digital platforms’

relationships with publishers?

-

No. The AICOA and OAMA do not contain specific rules governing digital platforms’ relationships with publishers. Senator Amy Klobuchar has introduced a separate bill, the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act, which would give publishers a six year safe-harbor from antitrust law in order to negotiate collectively against covered online platforms.21

-

7. Will the authority need to establish the effects of certain

conduct in order to establish a breach of the proposed rules?

-

If passed, the AICOA’s general self-preferencing and terms of service discrimination provisions would require plaintiffs to show “material harm to competition.” The remaining provisions do not contain affirmative effects requirements, but would not apply if the defendant shows a lack of “material harm to competition.” In order words, the burden would be shifted from the plaintiff to the defendant for these provisions. As a matter of general antitrust law, harm to competition typically means that prices are rising, output is falling, or innovation or quality is decreasing; it is not sufficient to show that the challenged conduct harms competitors.

The OAMA would not require plaintiffs to establish the effects of challenged conduct.

-

8. Will firms be able to defend or objectively justify their

conduct under the proposed rules?

-

The AICOA would take into account the overall competitive effect of conduct when determining liability. In particular, the self-preferencing and discrimination provisions require plaintiffs to show “material harm to competition.”22 And under the other prohibitions, defendants can avoid liability by showing, by a preponderance of the evidence (>50%), that conduct did not materially harm competition.23

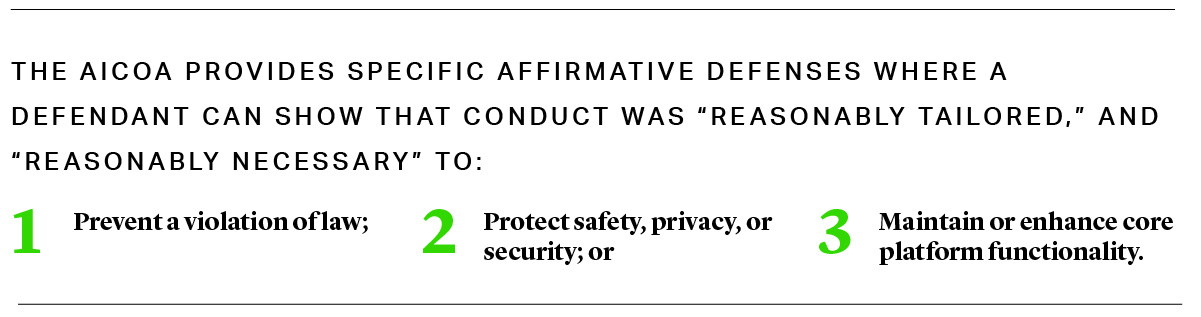

The AICOA also provides specific affirmative defenses where a defendant can show that conduct was “reasonably tailored,” and “reasonably necessary” to: (1) prevent a violation of law; (2) protect safety, privacy, or security; or (3) maintain or enhance core platform functionality.24

The OAMA contains affirmative defenses, albeit on fairly narrow grounds.

In particular, covered companies can defend actions by showing they were necessary to: (1) achieve user privacy, security, or digital safety; (2) prevent spam or fraud; or (3) prevent a violation of, or comply with, Federal or State law.25 However, the covered company must also show “by a preponderance of the evidence” (>50%) that such actions were:

- Applied on a demonstrably consistent basis to the covered platform’s apps, its business partners’ apps, and other apps;

- Not used as a pretext to exclude, or impose unnecessary or discriminatory terms on, third-party apps, in-app payment systems, or app stores; and

- Narrowly tailored and could not have been achieved through a less discriminatory and technically possible means.

The OAMA substantially shifts the burden of proof on these issues. Under current doctrine, protecting user privacy or security is considered a permitted procompetitive justification that defendants can avail themselves of. If a defendant takes an action to protect user privacy or security, it is not required to demonstrate that its action was the least restrictive option available.26 By contrast, under the OAMA, if a defendant takes an action to protect user privacy or security, the defendant is liable unless it can show, by clear and convincing evidence, that no less discriminatory alternative existed.

-

9. What procedural safeguards would the proposed rules include?

-

If passed, the AICOA and OAMA would be enforced in the same manner as the existing antitrust laws. In particular, both bills could be enforced through the courts, where Defendants would have all the rights available within the American legal system. Further, as is true today, the FTC could bring cases through its internal administrative system.27 In the FTC’s administrative system, claims are initially presided over by an FTC administrative law judge and then must be appealed to the FTC Commission (which decided to bring the claims) before they can be appealed to a Federal appellate court.28

Both bills could also be enforced through agency investigations.29 Specifically, in addition to bringing claims, enforcers could issue broad subpoenas to investigate potential infringements. Responding to such subpoenas can often be quite burdensome, and can potentially take years.

Separately, when the agencies designate an online service as a covered platform, the owner of that service would have the right to challenge that designation in the DC Circuit within 30 days (whether or not the service was subject to an enforcement action in court).30

The agencies would also be tasked with publishing enforcement guidelines within 270 days of passage detailing how they would assess “material harm to competition,” affirmative defenses, and fines under the Act.31

-

10. What kinds of penalties or remedies will the authority be

able to impose following a breach of the proposed rules?

-

If passed, under the AICOA, enforcers could seek to impose penalties of up to 10% of a covered platform operator's total global annual turnover.32 To provide further transparency, the Act requires the agencies within 270 days to draft enforcement guidelines detailing how they will assess penalties.33 Injunctive relief would also be available.

0%UNDER THE AICOA, ENFORCERS WOULD BE ABLE TO SEEK PENALTIES UP TO 10% OF THE DEFENDANT'S GLOBAL ANNUAL TURNOVER.Under the OAMA, app developers could bring private suits for treble damages and State Attorneys General could sue for such damages in the name of developers from their states.34 The OAMA does not include penalty provisions. It would be enforced by the FTC and DOJ in the same manner as the current antitrust laws in the civil context.35 In short, Federal enforcement would mostly be limited to injunctive relief, though in rare cases the DOJ may also seek equitable monetary remedies (e.g., disgorgement and restitution).36

-

11. Have any guidance or reports been issued regarding the proposed rules?

-

No, as neither the AICOA nor OAMA have been passed into law. However, the agencies would have to produce enforcement guidelines within 270 days if the legislation is passed.37

0 daysTO PROVIDE FURTHER TRANSPARANCY, THE ACT REQUIRES THAT WITHIN 270 DAYS THE AGENCIES DRAFT ENFORCEMENT GUIDELINES DETAILING HOW THEY WILL ASSESS PENALTIES. -

12. Will the new regime be competition based, or does it target

other types of conduct, such as consumer protection, moderation of

content, or privacy?

-

As a general matter, the AICOA and OAMA are competition-based. However, there is debate over whether the AICOA would have second order effects on content moderation by covered platforms (e.g., whether the prohibition on terms of service discrimination against business users would limit the ability of platforms to take down misinformation posted by fringe media outlets).

This debate has become a serious barrier to the bills' passage. Progressives are pushing for amendments to explicitly prevent the AICOA from becoming a tool to punish platforms that moderate politically sensitive speech.38 However, some Republicans have stated that such an amendment would be a non-starter if they are to support the bill’s passage.39 For the AICOA to become law, it would need sixty votes in the Senate, which requires bipartisan support. Given the debate on content moderation, it is unclear whether such bipartisan support is possible.

-

13. What is the current enforcement practice with respect to conduct

that is expected to be addressed by the digital regulation?

-

Unlike in other jurisdictions, US agencies have not historically challenged self-preferencing by tech companies. This is likely because self-preferencing, while subject to US antitrust law, would rarely rise to the level that would trigger a potential law violation, for three main reasons. First, under US antitrust law, dominant companies are only required to do business with competitors in specific narrow circumstances, and do not have a general obligation to give competitors the same treatment they give themselves.40 Second, self-preferencing would only be actionable if engaged in by a monopolist and if it is likely to result in acquiring or maintaining monopoly power. Third, the effects of the self-preferencing would have to result in net harm to consumers, so courts would weigh the benefits of self-preferencing against its harms. This would change under the AICOA and OAMA, and greater enforcement would be expected accordingly.

Generally, however, enforcement of antitrust law in digital markets by the FTC, DOJ, and State Attorneys General has ramped up in recent years. For example following cases are currently pending before the courts:

- The DOJ and a coalition of State Attorneys General are challenging Google’s distribution agreements with mobile carriers and Apple, alleging that the agreements are exclusionary and have allowed Google to maintain a monopoly in general search services and search advertising. The of State Attorneys General had also challenged restrictions on certain specialized vertical search providers’ access to Google’s Search results page.41 but those claims were denied by the judge in August 2023 due to plaintiffs’ failure to demonstrate harm in the relevant antitrust markets.42 The DOJ pressed its claims against Google in a 12-week trial in the U.S. District for the District of Columbia, concluding on November 16, 2023.43 District Court Judge Amit Mehta is expected to issue a ruling sometime in 2024.44

- A coalition of State Attorneys General led by Texas is challenging practices on Google’s ad-exchange that the coalition alleges coerce publishers on the exchange into also using Google’s ad-serving tools. At the beginning of 2023, the DOJ and a separate coalition of State Attorneys General filed a similar lawsuit, which included a challenge to Google’s 2008 acquisition of DoubleClick.

- The FTC and 17 State Attorneys general filed an antitrust suit against Amazon in September 2023.45 The FTC alleges that Amazon uses algorithms to detect and punish third-party sellers who offer products at lower prices elsewhere online and to discipline rival online stores who undercut Amazon’s prices. It also alleges that Amazon anticompetitively bundles access to Prime eligibility for sellers with use of its logistics services, such as shipping and warehousing.46

-

14. Are there merger rules specific to digital platforms in the US?

-

No. Neither the AICOA nor the OAMA would create new merger rules for digital platforms. A separate piece of potential legislation, the Platform Competition and Opportunity Act, would substantially limit acquisitions over USD 50 million by Google, Apple, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft.47 However, given its lack of any progress, the PCOA is not expected to pass.

$0mnA SEPARATE PIECE OF LEGISLATION PENDING IN CONGRESS WOULD SUBSTANTIALLY LIMIT ACQISITIONS OVER USD 50 MILLION BY GOOGLE, APPLE, META, AMAZON, AND MICROSOFT.

Contacts

D. Bruce Hoffman

Partner

Brian Byrne

Partner

Elaine Ewing

Partner

George S. Cary

Partner

Bay Area

T: +1 451 796 4410

Washington, D.C.

T: +1 202 974 1920

gcary@cgsh.com

V-Card

Molly Ma

Associate

Alexi T. Stocker

Associate