Led in part by a surge in international trade and investment on the continent, cross-border investment disputes involving African parties have surged in recent years. International arbitration has become the principal resolution mechanism for these disputes.

Between the early 2010s and 2020, both the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) witnessed a surge in the number of African parties involved in arbitrations, with LCIA caseloads including sub-Saharan parties growing from 4.5% in 2011 to 11.7% in 2020. Combined caseloads from the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) that involve at least one party from a sub-Saharan African state have also risen, nearly tripling1.

As arbitration becomes the preferred method for dispute settlement for African parties, we delve into the latest trends across the continent, which were discussed during a recent webinar hosted by Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton on the topic “Africa Outlook: Arbitration Trends”. We report on the discussions by the various panelists below.

Led in part by a surge in international trade and investment on the continent, cross-border investment disputes involving African parties have surged in recent years. International arbitration has become the principal resolution mechanism for these disputes.

Between the early 2010s and 2020, both the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA) and the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) witnessed a surge in the number of African parties involved in arbitrations, with LCIA caseloads including sub-Saharan parties growing from 4.5% in 2011 to 11.7% in 2020. Combined caseloads from the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) that involve at least one party from a sub-Saharan African state have also risen, nearly tripling1.

As arbitration becomes the preferred method for dispute settlement for African parties, we delve into the latest trends across the continent, which were discussed during a recent webinar hosted by Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton on the topic “Africa Outlook: Arbitration Trends”. We report on the discussions by the various panelists below.

Arbitration in OHADA and Non-OHADA

The private sector in Africa is increasingly resorting to arbitration to settle disputes with states or state-owned enterprises (SOEs). According to Mr. Thierno Olory-Togbe from the African Legal Support Facility, this growing use of arbitration is encouraged by several factors, including:

As with other regions, the COVID-19 pandemic has also disrupted economic and financial relations in Africa.

The inability of governments and private parties to fulfil their contractual obligations has given rise to disputes in sectors from infrastructure to power generation and mining. As the COVID-19 crisis continues, states are calling for increased legal and technical support, including the option to attend virtual arbitration proceedings. African arbitral institutions have well-adjusted to these new challenges.

Nigeria

In Nigeria, the National Arbitration Policy Committee recently proposed the development and adoption of National Arbitration Policies, including discussions around the appointment of arbitrators, the choice of arbitral seats, setting aside arbitral awards and rules against corruption.

According to Mrs. Folashade Alli, Founding Partner at Folashade Alli & Associates, the Nigerian Attorney General’s office has also considered imposing a duty on parties to elect their arbitrators from a pool of qualified Nigerian arbitrators. Though some have welcomed this as a solution to the lack of diversity in arbitral tribunals, critics suggest that such a policy would be contrary to the principle of party autonomy and Nigeria’s Arbitration and Conciliation Act. Others have recommended, as a middle ground, limiting it to disputes involving State assets.

The dispute between P&ID and Nigeria involved a purported repudiation by the Federal Republic of Nigeria of a Gas Supply and Processing Agreement (GSPA). In 2012, P&ID commenced arbitration against Nigeria for breaches of the GSPA. The arbitral tribunal rendered an award in July 2015 deciding that Nigeria had repudiated the agreement by failing to meet its obligations, awarding P&ID $6.6mn in damages.

In 2019, the English High Court granted enforcement of the award. Nigeria applied to the same court for an extension to challenge the initial arbitral award as the deadline to commence setting aside proceedings had expired, asserting for the first time a prima facie case of fraud against P&ID. On September 4, 2020, having found strong prima facie evidence that the investment was procured through bribes and that the arbitration proceedings were tainted by fraud, the English courts decided to grant an extension to Nigeria to allow it to challenge the award under sections 67 and 68(2)(g) of the English Arbitration Act 1996.

Ghana

Ghanaian courts are increasingly willing to recognize and enforce arbitral awards, while the support of domestic courts has been decreasing. Mr. Kizito Beyuo, Managing Partner at Beyuo & CoI, reported on one instance in which a national court referred parties to arbitration, but then went on to appoint an arbitrator on behalf of the parties. The arbitrator subsequently declined jurisdiction because the parties had neither consented to arbitration, nor to the arbitrator’s appointment. On appeal, the judge held that the arbitrator was wrong in declining jurisdiction, on the basis that arbitrators have no inherent power to determine jurisdiction since that power is conferred by statute.

In another matter, a claimant filed for arbitration, but the respondent applied to a domestic court arguing that the pathological nature of the arbitration clause prevented the parties from settling their dispute by arbitration. The court rejected the respondent’s application, after reviewing the applicable arbitration clause. It held that the arbitrator had the power to determine its own jurisdiction.

The parties to a construction agreement providing for arbitration entered into litigation over a purported breach of contract. After the hearing had commenced, the defendant requested the court to refer the parties to arbitration in accordance with the terms of the underlying contract. A trial court rejected the request as being untimely pursuant to section 6(1) of the Alternative Dispute Resolution Act, 2010 (Act 798). However, the court on its own motion applied the provisions of section 7(5) of the Act and referred the parties to arbitration.

Following an unsuccessful appeal, the claimant requested Ghana’s Supreme Court to rule on the following issues: (i) whether the parties to a contract with an arbitration clause can resort to court proceedings in respect of matters covered by the arbitration clause; and (ii) if they can, what standards should apply to determine the question. Relying on Sections 6(1), 7(5) and 54(2) of the Act, the Supreme Court found that the parties had irrevocably waived their right to arbitration. Therefore, the court could not compel the parties to resort to arbitration.

Cameroon

National courts are still the primary forum for dispute resolution in Cameroon, even though efforts have been made to promote arbitration, particularly by local associations and universities.

The Association for the Promotion of Arbitration in Africa (APAA), for instance, has recently organized several trainings in Cameroon. Local law firms work alongside the Cameroon Bar Association and other institutions such as the ICC to promote arbitration, while universities are increasingly teaching arbitration courses.

The role of local arbitration institutions in Cameroon is also significant, according to Ms. Aurélia Mafongo Kamga, Associate at Chazai & Partners. In particular, the Center for Arbitration and Mediation of the Groupement Interpatronal du Cameroun (GICAM) is a rising arbitration institution which now offers mediation services. During the pandemic, arbitration has been a flexible dispute settlement mechanism and it is now increasingly common to conduct virtual arbitration proceedings in the country.

Côte d’Ivoire

There are some difficulties in enforcing arbitral awards in Côte d’Ivoire, but potential solutions are on the horizon, says Olivier Amalaman, Partner at KSK Avocats.

Under Ivorian law, a decision denying enforcement of an award is subject to appeal, which can only be filed before the CCJA. In contrast, Article 32 of the OHADA Uniform Act on the Law of Arbitration states that a decision allowing enforcement of an award is not subject to appeal. Nevertheless, parties regularly launch appeals against orders granting enforcement of arbitral awards. According to the Ivorian Commercial Court of Appeal, the enforcement procedure is only applicable to awards rendered by an arbitral tribunal seated in OHADA States. For non-OHADA States, enforcement should be governed by domestic law, as required by the New York Convention.

As such, the Ivorian Commercial Court of Appeal has repeatedly ruled that the enforcement of arbitral awards rendered in non-OHADA States should align with the domestic enforcement procedure applicable to foreign judgments. According to Article 346 of the Ivorian Code of Civil Procedure, decisions granting enforcement of foreign judgements are subject to appeal. Some critics state that this is a misinterpretation of the New York Convention on Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, which applies the domestic law enforcement procedure, irrespective of the seat of the award.

To address this issue, some suggest that decisions rendered following an appeal against an enforcement decision be made systematically and directly enforceable without requiring any registration formalities. As a result, the beneficiary of the award would be able to enforce its decision and thus possibly the award, unless there was an appeal against the decision.

Finally, there has been a call for greater awareness on the part of domestic courts of the need for speedy and efficient arbitration proceedings, to prevent parties from using domestic procedures to delay the timely enforcement of arbitral awards.

The Work of Arbitral Institutions in Africa

According to Ms. Diamana Diawara, ICC Regional Executive Director for Arbitration and ADR in Africa, and in reference to several surveys, the ICC remains the preferred institution for parties involved in arbitration. This follows new services developed by the ICC to improve efficiency, reduce costs and address clients’ concerns about time management, such as the ICC expedited procedure introduced in 2017 and the ICC emergency arbitration mechanism introduced in 2012. The ICC has also focused on improving transparency, for instance by publishing notes explaining how the ICC Rules work in practice, and on addressing the need to include local practitioners at the international and regional level to improve diversity.

One further critical concern has been diversity, and the ICC has sought to increase the number of African practitioners in its Court. Other recent highlights include the launch of the ICC Africa Commission to provide guidance to the ICC, increase awareness, and encourage the use of arbitration in Africa.

The Rise of Regional Institutions

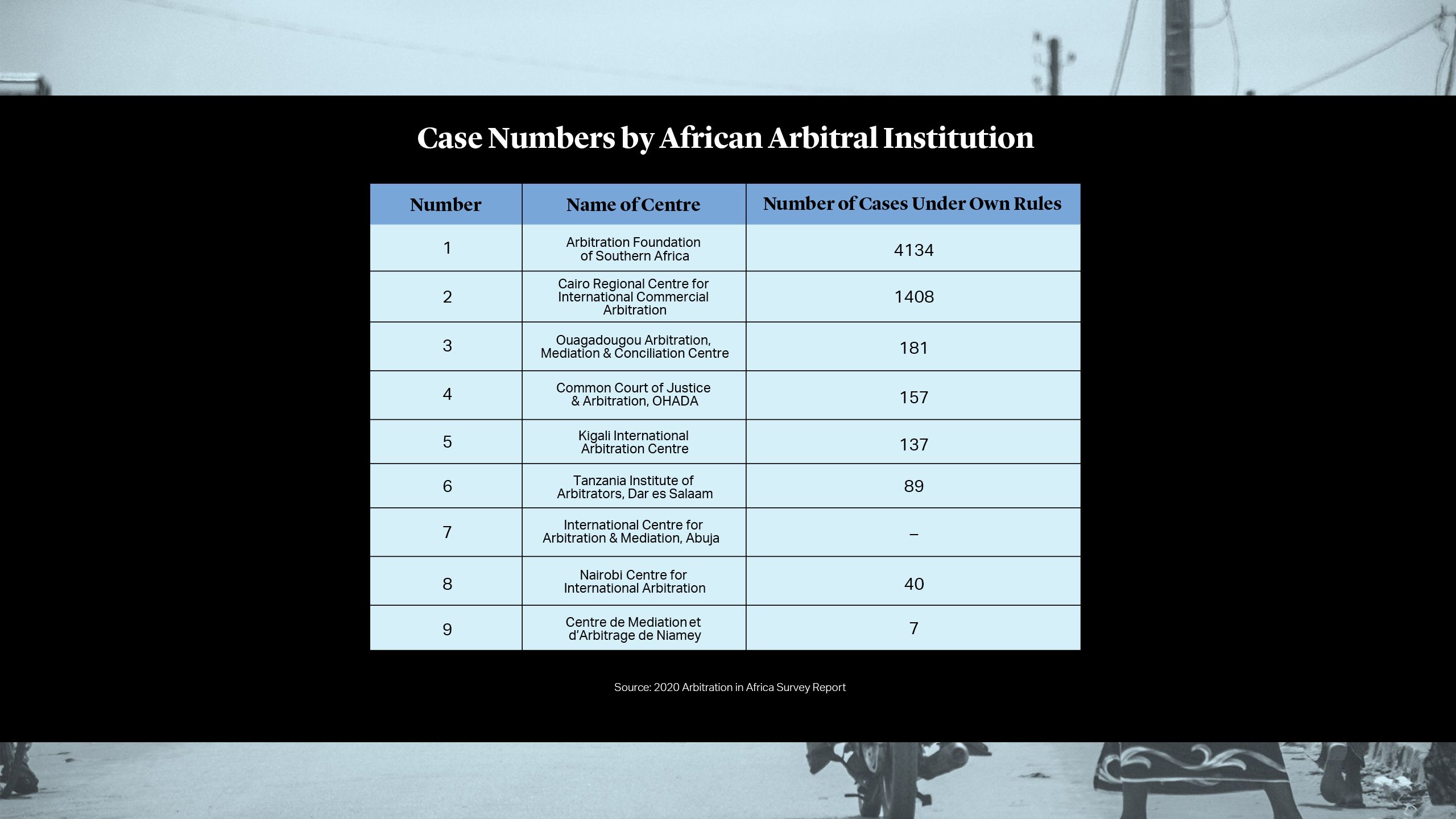

While the role of traditional arbitral institutions continues to grow, so too has the popularity of regional African institutions. In particular, those participating in arbitrations regularly rank institutions in Cairo, Nairobi and Lagos amongst the most preferred on the continent2.

Part of the Lagos Court of Arbitration’s (LCA) popularity could be the result of its focus on developing schemes to offer micro, small and medium-sized enterprises fast and affordable access to arbitration, says Mr. Godwin Omoaka, SAN, Partner at Templars and board member at the LCA. For example, the LCA provides expedited rules for small disputes ranging from 250,000 to 10,000,000 Naira (approximately $600 to $24,000) which the parties can opt for before or after the dispute arises. The LCA also published expedited rules for emergency arbitrators in 2018 to give parties fast access to interim measures. To address issues like cost-efficiency, other arbitral institutions might consider revising their rules to include similar procedures.

In Egypt, the Cairo Regional Center for International Commercial Arbitration (CRCICA) is also increasingly seen as a friendly arbitral institution, issuing new dispute board rules as an optional alternative to FIDIC board rules – a move popular amongst stakeholders that has been made by very few other institutions, according to CRCICA’s Director Dr. Ismail Selim.

Measures introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic have also been well-received. This included the CRCICA issuing regular communications encouraging the use of technology and virtual hearings, with virtual hearings now becoming the norm. Other measures have included amending the CRCICA 2011 Rules, which closely mirror the 2010 UNCITRAL Rules, with the aim of adopting expedited procedures, emergency arbitration procedures, and provisions regulating joinder of proceedings amongst other matters.

Christopher P. Moore

Partner

London

T: +44 20 7614 2227

New York

T: +1 212 225 2836

cmoore@cgsh.com

V-Card

Laurie Achtouk‑Spivak

Counsel

Paris

T: +33 1 40 74 68 00

lachtoukspivak@cgsh.com

V-Card

Naomi Tarawali

Associate

London

T: +44 20 7614 2304

ntarawali@cgsh.com

V-Card

Sarah Schröder

Associate