In sub-Saharan Africa, a growing number of state-owned investment institutions are looking to deploy capital domestically and abroad. With a mandate for both unlocking the value of strategic country assets, as well as investing in global markets to create savings for further generations, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) and public pension funds (PPFs) are becoming increasingly important sources of capital on the African continent.

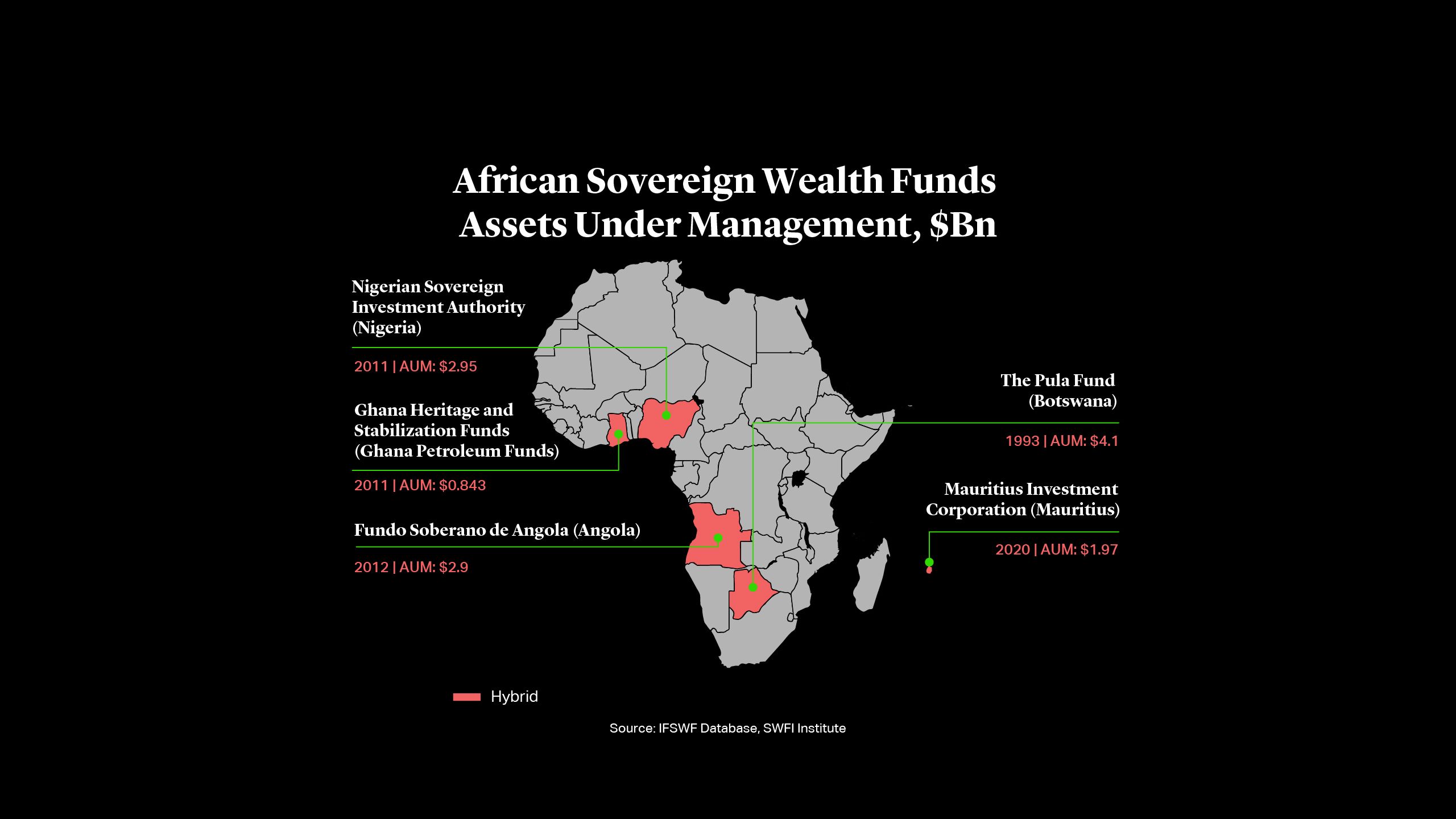

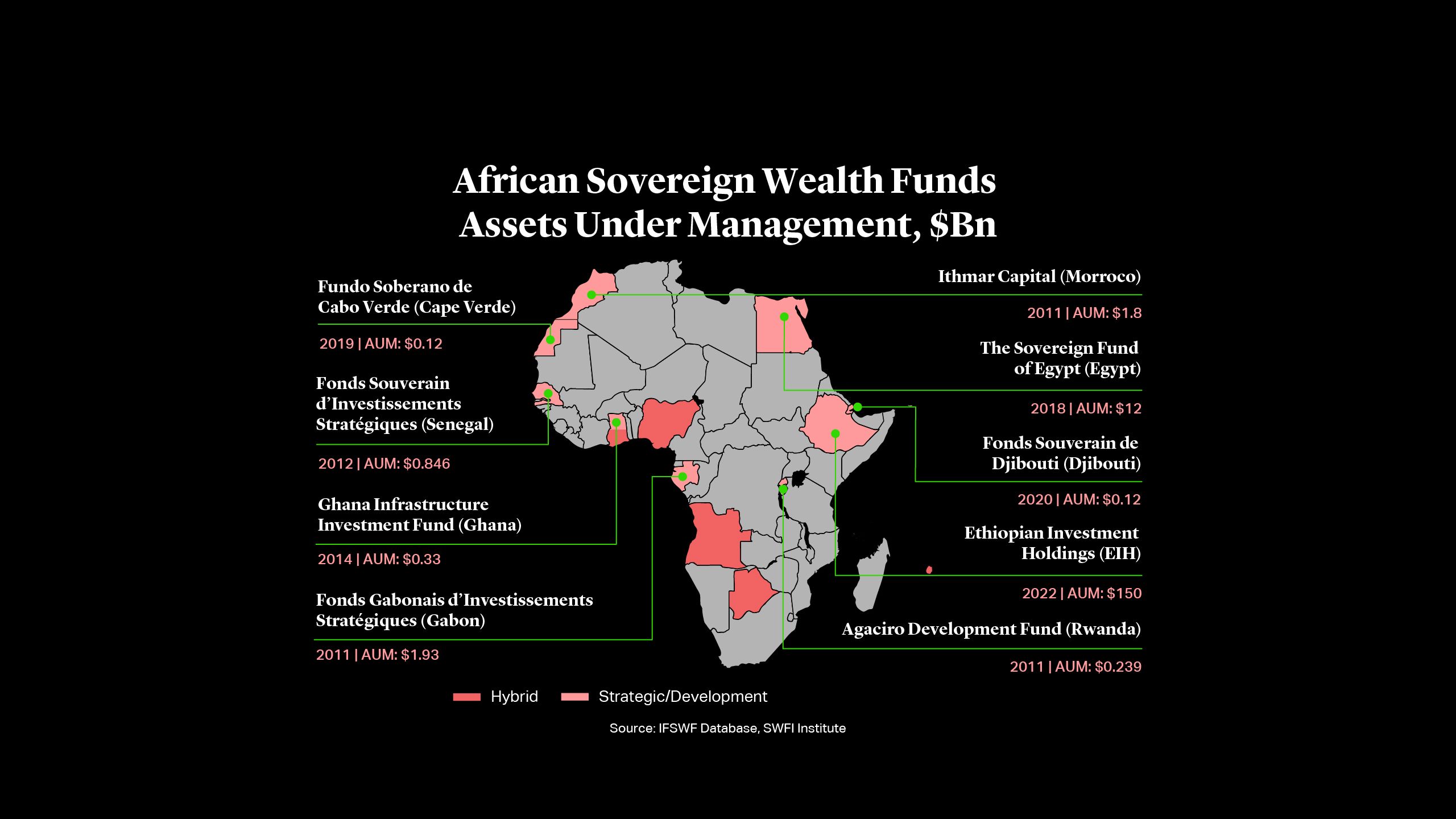

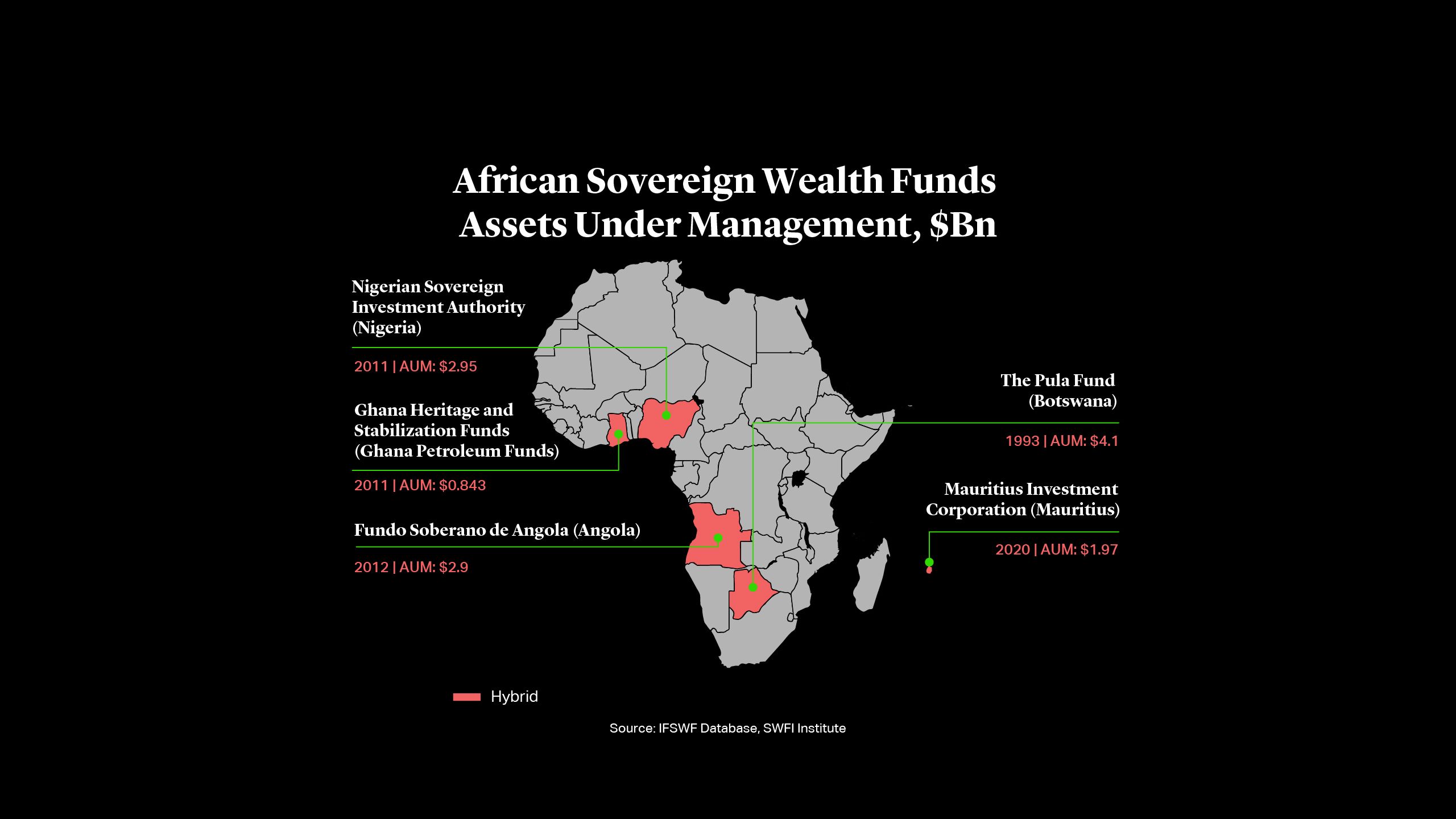

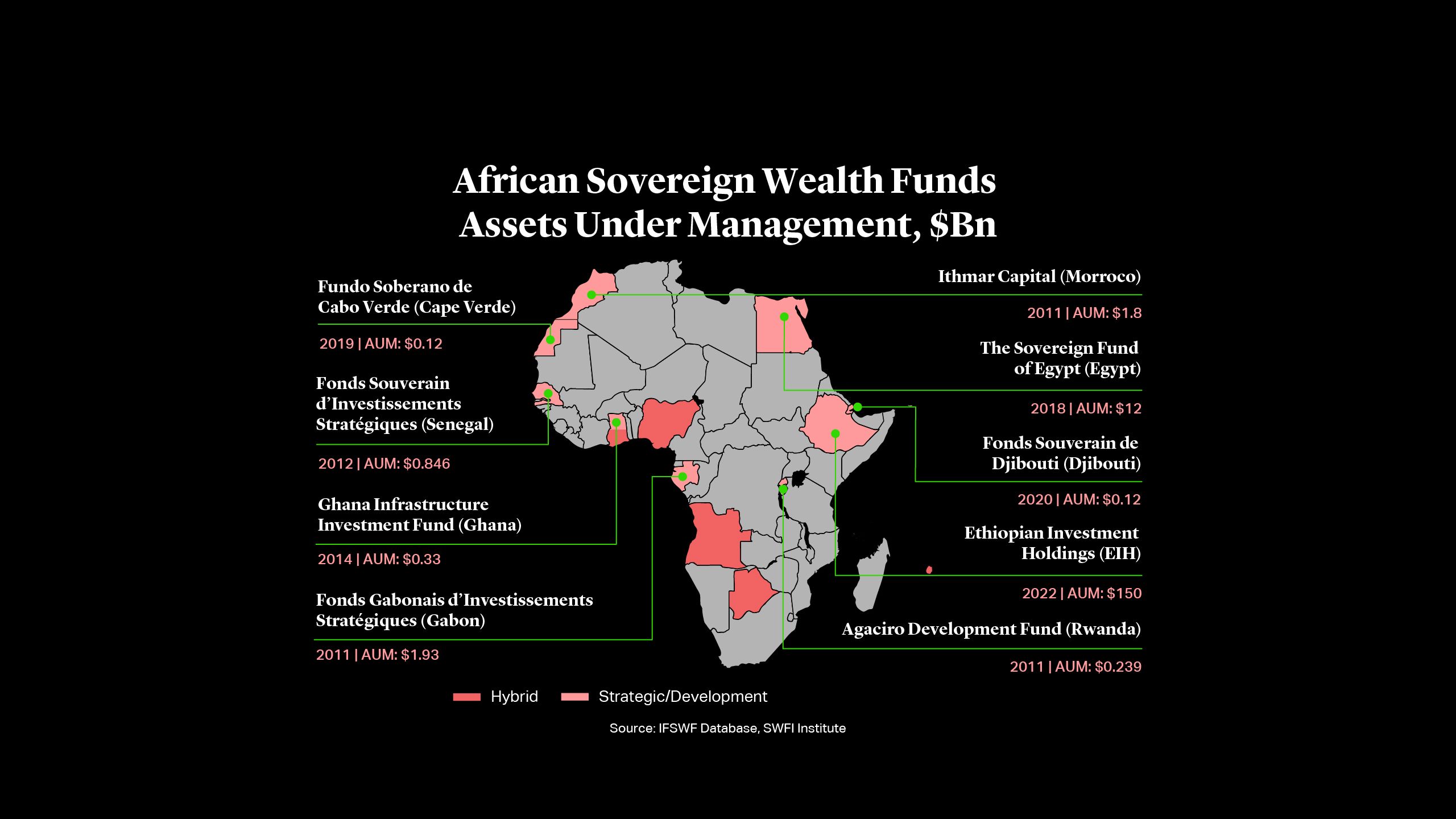

With an estimated $160bn worth assets under management in SWFs and $244bn in PPFs, sub-Saharan Africa has by far the smallest volume of assets under management globally1. The region is dwarfed by the $4.94tn and $4.1tn managed by SWFs in Asia and MENA, respectively2. But the size of these SWFs is commensurate with the gross domestic product of their respective national economies, reflecting lower savings and tax rates in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as more limited access to fossil fuel revenues across the region.

15 new sovereign wealth funds were formally established in sub-Saharan Africa between 2010 and 2022. Additionally, in November 2022 Mozambique’s government approved a draft bill on the creation of the new Fundo Soberano de Moçambique, which will use revenues from oil exploration to fund economic and social development in the country3. Plans for two sub-regional funds were also approved in 2022 in sub-Saharan and northern Africa, including the Lagos State Wealth Fund in Nigeria4 and the Suez Canal Authority Fund in Egypt5.

In sub-Saharan Africa, a growing number of state-owned investment institutions are looking to deploy capital domestically and abroad. With a mandate for both unlocking the value of strategic country assets, as well as investing in global markets to create savings for further generations, sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) and public pension funds (PPFs) are becoming increasingly important sources of capital on the African continent.

With an estimated $160bn worth assets under management in SWFs and $244bn in PPFs, sub-Saharan Africa has by far the smallest volume of assets under management globally1. The region is dwarfed by the $4.94tn and $4.1tn managed by SWFs in Asia and MENA, respectively2. But the size of these SWFs is commensurate with the gross domestic product of their respective national economies, reflecting lower savings and tax rates in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as more limited access to fossil fuel revenues across the region.

15 new sovereign wealth funds were formally established in sub-Saharan Africa between 2010 and 2022. Additionally, in November 2022 Mozambique’s government approved a draft bill on the creation of the new Fundo Soberano de Moçambique, which will use revenues from oil exploration to fund economic and social development in the country3. Plans for two sub-regional funds were also approved in 2022 in sub-Saharan and northern Africa, including the Lagos State Wealth Fund in Nigeria4 and the Suez Canal Authority Fund in Egypt5.

Multiple Mandates

Unlike the SWFs of the Gulf Region (which are some of the most renowned and largest scale SWFs in the world), sub-Saharan African SWFs are faced with a more complex set of conflicting national priorities. On the one hand, sub-Saharan African countries need to create savings and fiscal buffers for when local commodity extraction is no longer viable. On the other hand, they need to invest enormous capital to urgently attend to major development issues, including poverty, chronic unemployment, limited access to basic public services, and good quality education.

Mandates for Africa’s SWFs consequently vary from country to country based on their unique development needs. But these mandates broadly fall into three main buckets. Stabilization Funds such as Botswana’s Pula Fund and Namibia’s commodity-backed Welwitschia Fund predominantly act as a buffer mechanism to cover fiscal deficits in uncertain economic times. They tend to invest in more liquid assets, including stocks and bonds. Savings Funds such as Mozambique’s planned Fundo Soberano de Moçambique and the Lagos State Wealth Fund are less focused on short-term liquidity and more on creating value for future generations. Meanwhile, Strategic Funds from Gabon’s FGIS to Angola’s FSDEA and Ethiopia’s Investment Holdings (EIH) are more focused on stimulating domestic development by making anchor investments into local infrastructure projects.

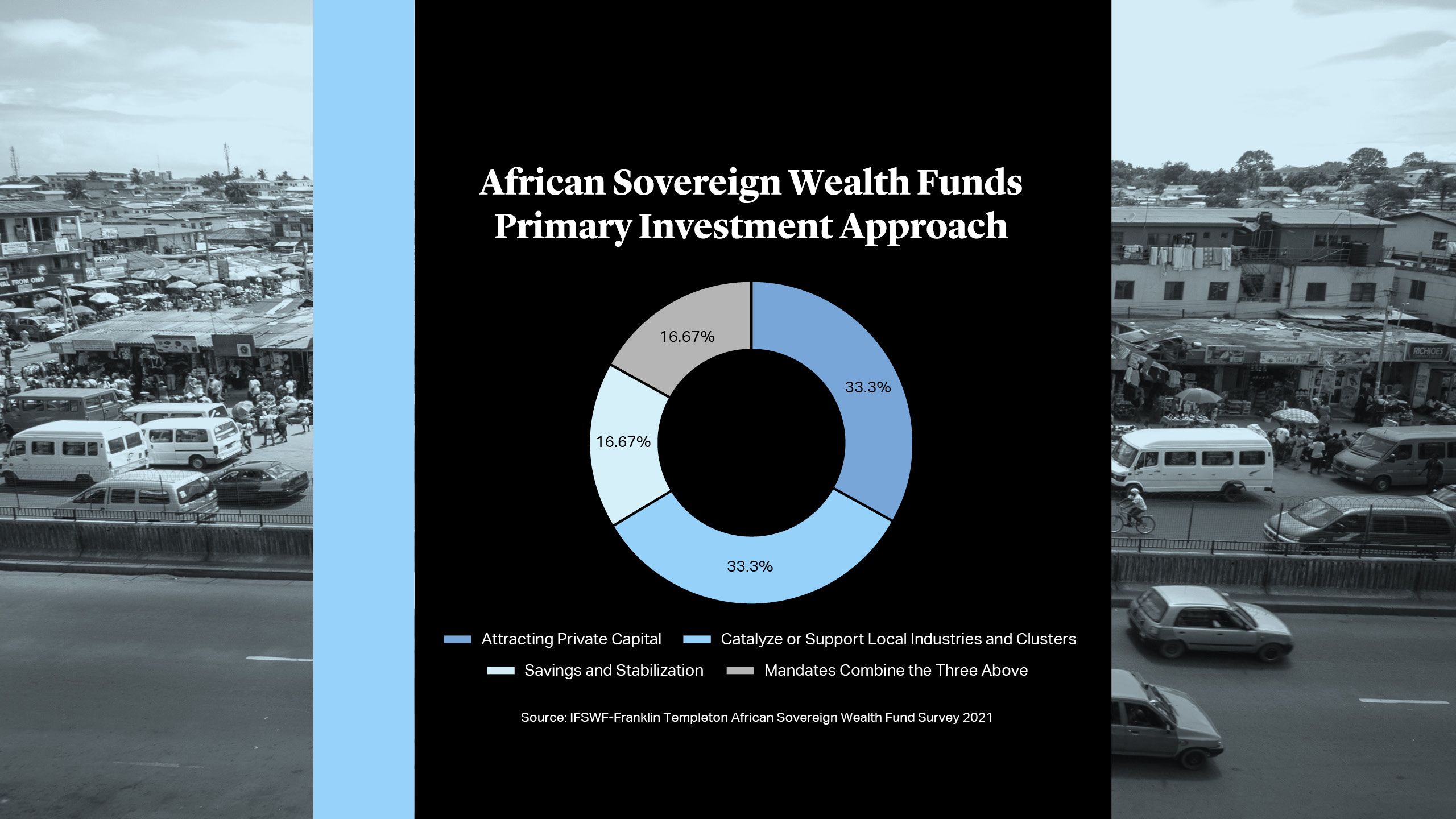

Overall, 33% of sub-Saharan SWFs are strategic, 13% savings and 24% stabilization funds, according to analysis by Global Sovereign Wealth Fund6. Analysis by the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF) shows that at least a third (33.3%) of African SWFs have a core strategy of attracting foreign private capital to co-invest alongside them on local development projects7. Meanwhile, a number of African SWFs have multi-mandate strategies focused on saving, stabilization funding and strategic investment8.

In many ways, African SWFs with an infrastructure development strategy play a similar role to African multilateral development finance institutions like the African Development Bank (AfDB) and the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), which African SWFs often partner with. For instance, Senegal’s Fonds Souverain d’Investissements Stratégiques (FONSIS) provided sovereign guarantees and equity investment (alongside a consortium of public and private sector investors) towards the €43mn local construction of the 30-Megawatt Senergy plant in 2017, West Africa’s largest PV solar plant at the time. Since then, FONSIS has participated in the financing of three other local PV solar projects as part of Senegal’s Scaling Solar Project which has boosted national solar capacity by over 50%9.

Additionally, African SWFs play an important role in developing robust local financial markets infrastructure. According to the IFSWF, several African SWFs are anchor limited partners in private equity funds intended to invest in the African healthcare and renewable energy sectors – for example, FONSIS anchored the fundraising for Teranga Capital, a private equity impact fund dedicated to Senegalese high growth small and medium-sized enterprises10. The Nigerian Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA) has also provided the seed capital for two major private sector financial markets institutions: (i) Nigeria’s Infrastructure Credit Guarantee Limited, which provides local guarantees to enhance the credit quality of debt instruments issued by companies investing in Nigerian infrastructure projects and (ii) the Nigerian Mortgage Refinance Company, a company that intervenes in the local residential mortgage markets to refinance loans at cheaper interest rates.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s SWFs also vary in respect of their permitted investment destinations – domestic or foreign. For example, Ghana’s Heritage and Stabilization Funds (two petroleum savings funds) are prohibited by law from making domestic investments11. On the other hand, Gabon’s FGIS has 78% of its portfolio invested in Gabon’s domestic economy, targeting a wide range of local development projects12.

Spotlight on Ethiopia Investment Holdings (EIH)

Ethiopia’s EIH is less than a year old but has already amassed an estimated $150bn in assets under management13, counting 30 state-owned enterprises, including Ethiopian Airlines in its portfolio14. The Ethiopian government’s strategic investment arm is now the continent’s largest sovereign wealth fund, according to the IFSWF15.

Set up to create wealth to finance development and improve the efficiency of state-owned assets through modern management practices aligned on international standards for corporate governance, EIH is making quick work to modernize and unlock value in Ethiopia’s economy.

In January, EIH entered into an agreement with the UAE’s Masdar to jointly develop two 500-megawatt solar projects. It also has plans to establish the Ethiopian Stock Exchange (ESX), which it intends to launch in 2024-5 with 50 listed companies16. EIH is also looking beyond its domestic market and is working to boost energy security by developing an oil storage facility in Djibouti17.

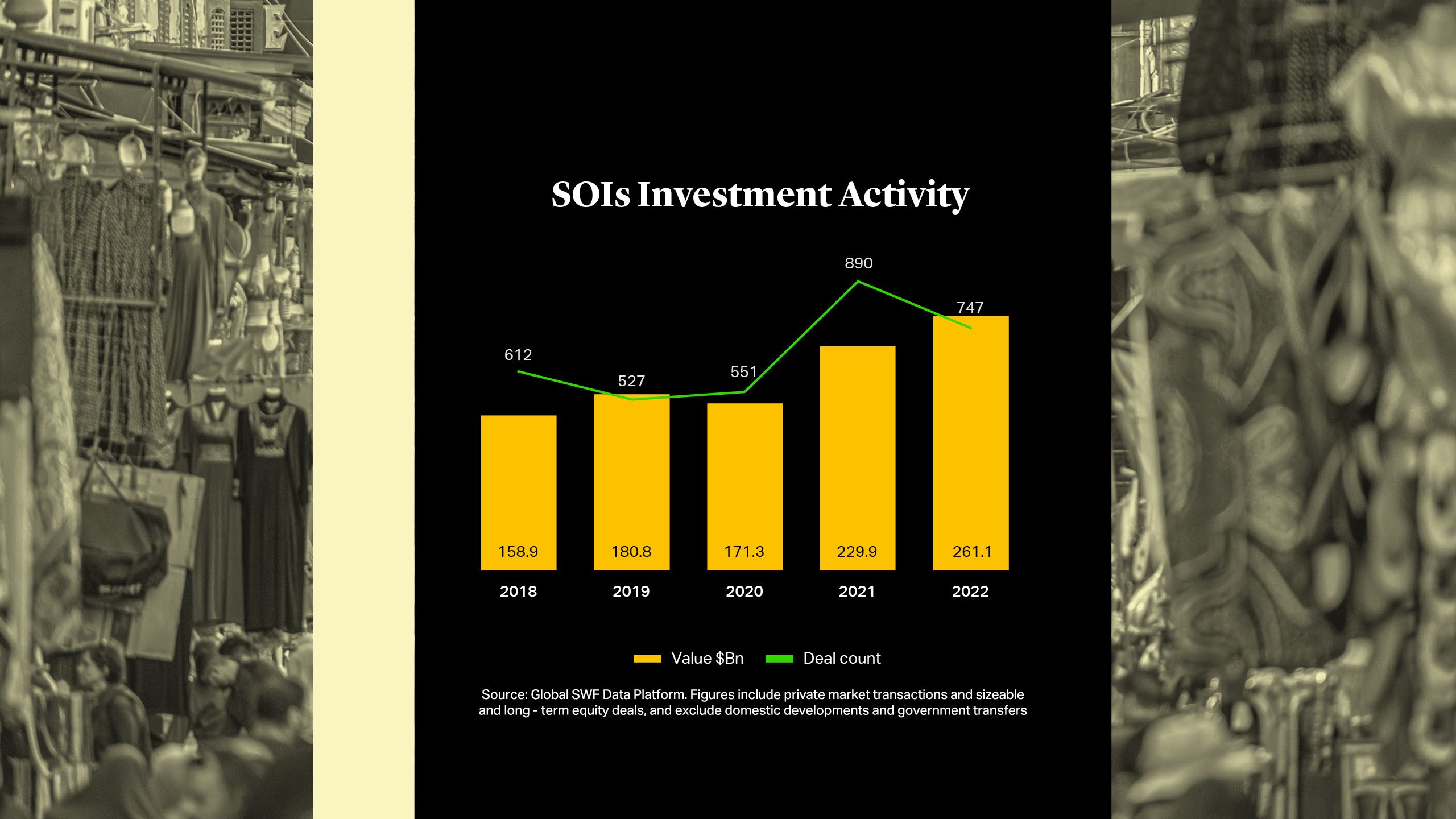

Inbound SWF Investment in Africa – Partnerships Between African and Gulf SWFs

Though the global sovereign wealth industry shrank in asset value for the first time on record in 2022, state-owned entities invested 38% more than they did in 2021, deploying an estimated $152.5bn in capital globally18. This occurred despite market headwinds, including high inflation, rising interest rates and geopolitical concerns.

Developed markets (North America, Europe and Northeast Asia) continue to attract the majority of investment capital from the world’s state-owned investors, while investment in emerging markets was just over 20% of the total in 202219. Nonetheless, the African continent still offers attractive growth and strategic investment opportunities for leading state-owned investors.

Indeed, for the larger scale SWFs of the Middle East, Africa is a particular focus. Oman, Abu Dhabi and Dubai are eying direct investments in African ports and other infrastructure via their SWFs to secure resources and competitive trade terms20. In January last year, Oman’s Investment Authority (OIA) signed an MoU with Tanzania to develop the Malindi Tourist Port in Zanzibar, while a publicly traded holding company that exclusively manages port infrastructure in Abu Dhabi (and is also a portfolio company of one of the UAE SWFs) has signed a framework to develop maritime services and infrastructure in Angola21.

Egypt and the Suez Canal region have also attracted notable interest, in part due to the abundance of natural energy sources (in addition to Egypt’s strategic geopolitical position amongst Arab nations), offering a strong diversification play for countries in the Gulf. The Sovereign Fund of Egypt (TSFE) has signed partnerships with a leading Abu Dhabi-based SWF, while at COP27 Oman’s OIA signed an MoU for a 10% stake in the $1.5bn 1.1-Gigawatt Suez Wind Energy Project22. Qatar Investment Authority is also said to be considering a $1bn renewables investment in the Suez Canal Economic Zone, as well as investing up to $2.5bn in other Egyptian state-owned assets23.

Co-investment is also proving to be an avenue for Gulf funds to access African markets. Qatar Investment Authority, for example, is the anchor investor in the Rwanda Social Security Board (RSSB) $250mn Virunga Africa Fund I24.

The signing of the Rabat Declaration in June 2022 is set to solidify Gulf interests in the continent. Several leading UAE SWFs and Kuwait’s Authority joined the AfDB and the sovereign funds of Angola, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Morocco, Nigeria, Rwanda and Senegal to create the African Sovereign Investors Forum (ASIF), a platform to promote investment on the continent25. ASIF will focus on mobilizing capital and equity, promoting green projects and investing in logistics to improve interconnectivity across the continent. ASIF is another example of how sovereign wealth funds are a growing source of capital on the African continent.

Governance Challenges in Turbulent Economic Times

Given the historic challenges that sub-Saharan African economies have faced, including in the areas of governance and political stability, and the perceived risk and the adverse impact on the credit quality of sub-Saharan African issuers, the African SWFs created in the past decade were established with the highest principles of transparency and accountability in mind. These African SWFs were designed to have independent decision-making and formal corporate governance structures allowing them to withstand political pressures and maintain the integrity of the SWFs through political transitions and government change. Six sub-Saharan African SWFs are “full members” of the IFSWF, meaning they have formally endorsed the Santiago Principles which lay out international best practices for SWF management26. Another three sub-Saharan African SWFs are “associate members” of the IFSWF, meaning they are in the process of completing relevant institutional arrangements or require certain amendments to their national laws to become a full member of the IFSWF in compliance with the Santiago Principles27.

Santiago Principle 1.1 states that “the legal framework for the SWF should ensure legal soundness of the SWF and its transactions” and Santiago Principle 1.2 provides that “the key features of the SWF’s legal basis and structure, as well as the legal relationship between the SWF and other state bodies, should be publicly disclosed”28. Consequently, nearly all the sub-Saharan African SWFs have been established as independent professional institutions with boards made up predominantly of non-government directors – in some cases like that of the NSIA the board reports to a second higher level oversight body29.

According to the IFSWF, around three-quarters of sub-Saharan African SWFs are structured as independent legal entities (such as corporations) rather than as “account” or trust entities30. The use of corporate entities with independent legal status rather than a pool of national funds held on trust means that: (i) the SWF can credibly raise additional capital in international debt markets secured against ring-fenced assets which the SWF holds full legal and beneficial ownership in (thus avoiding issues of sovereign immunity coming into play) and (ii) the SWF can gain the confidence of foreign private sector investors that act as co-investment counterparties in the SWF’s local development projects. In their efforts to attract foreign co-investors into riskier development projects, African SWFs are even at times willing to experiment with asymmetric co-investment structures – for example, the SWF may take a subordinated equity stake vis-à-vis private investors, exposing the SWF to the first loss in the event that the underlying project does not generate the required returns31.

The COVID-19 pandemic heavily constrained the budgets of many sub-Saharan African governments, which were already stretched thin and put additional pressure on their fiscal positions. Several African SWFs were hit with a ‘double whammy’ - governments in Angola, Botswana, Ghana and Nigeria made withdrawals from their stabilization and savings funds to finance urgent public spending in response to, and to mitigate the impact of, the COVID-19 pandemic and related containment measures32. Meanwhile, inflows of excess national commodity sector revenues into African SWFs slowed down as such funds needed to be allocated towards unexpected pandemic expenditures. According to the IFSWF, the greater likelihood of withdrawals from African SWFs to fund current budget needs has affected the long-term strategies of African SWFs, as they have to rethink their portfolio allocations. Urgent government withdrawals need to be funded by the quick liquidation of low risk assets held by SWFs (such as investment grade bonds) but this competes with the dual mandate of several African SWFs to invest long-term patient capital in riskier illiquid assets (such as equity investments behind infrastructure projects).

These challenges will become more acute as benchmark interest rates continue to increase and the world moves out of the era of ‘cheap money’. Sub-Saharan African countries are finding it harder to raise debt finance on international capital markets due to prohibitively high interest rates. Shut out of international capital markets, the temptation will increase for sub-Saharan African governments to increase their drawdowns from national savings and stabilization funds to fund their operating expenditures. It is critical that African SWFs continue to maintain their independent governance frameworks, which were carefully developed over the last decade, and remain focused on their long-term goals regarding portfolio allocation and national development strategies.

Governance Challenges in Turbulent Economic Times

Given the historic challenges that sub-Saharan African economies have faced, including in the areas of governance and political stability, and the perceived risk and the adverse impact on the credit quality of sub-Saharan African issuers, the African SWFs created in the past decade were established with the highest principles of transparency and accountability in mind. These African SWFs were designed to have independent decision-making and formal corporate governance structures allowing them to withstand political pressures and maintain the integrity of the SWFs through political transitions and government change. Six sub-Saharan African SWFs are “full members” of the IFSWF, meaning they have formally endorsed the Santiago Principles which lay out international best practices for SWF management26. Another three sub-Saharan African SWFs are “associate members” of the IFSWF, meaning they are in the process of completing relevant institutional arrangements or require certain amendments to their national laws to become a full member of the IFSWF in compliance with the Santiago Principles27.

Santiago Principle 1.1 states that “the legal framework for the SWF should ensure legal soundness of the SWF and its transactions” and Santiago Principle 1.2 provides that “the key features of the SWF’s legal basis and structure, as well as the legal relationship between the SWF and other state bodies, should be publicly disclosed”28. Consequently, nearly all the sub-Saharan African SWFs have been established as independent professional institutions with boards made up predominantly of non-government directors – in some cases like that of the NSIA the board reports to a second higher level oversight body29.

According to the IFSWF, around three-quarters of sub-Saharan African SWFs are structured as independent legal entities (such as corporations) rather than as “account” or trust entities30. The use of corporate entities with independent legal status rather than a pool of national funds held on trust means that: (i) the SWF can credibly raise additional capital in international debt markets secured against ring-fenced assets which the SWF holds full legal and beneficial ownership in (thus avoiding issues of sovereign immunity coming into play) and (ii) the SWF can gain the confidence of foreign private sector investors that act as co-investment counterparties in the SWF’s local development projects. In their efforts to attract foreign co-investors into riskier development projects, African SWFs are even at times willing to experiment with asymmetric co-investment structures – for example, the SWF may take a subordinated equity stake vis-à-vis private investors, exposing the SWF to the first loss in the event that the underlying project does not generate the required returns31.

The COVID-19 pandemic heavily constrained the budgets of many sub-Saharan African governments, which were already stretched thin and put additional pressure on their fiscal positions. Several African SWFs were hit with a ‘double whammy’ - governments in Angola, Botswana, Ghana and Nigeria made withdrawals from their stabilization and savings funds to finance urgent public spending in response to, and to mitigate the impact of, the COVID-19 pandemic and related containment measures32. Meanwhile, inflows of excess national commodity sector revenues into African SWFs slowed down as such funds needed to be allocated towards unexpected pandemic expenditures. According to the IFSWF, the greater likelihood of withdrawals from African SWFs to fund current budget needs has affected the long-term strategies of African SWFs, as they have to rethink their portfolio allocations. Urgent government withdrawals need to be funded by the quick liquidation of low risk assets held by SWFs (such as investment grade bonds) but this competes with the dual mandate of several African SWFs to invest long-term patient capital in riskier illiquid assets (such as equity investments behind infrastructure projects).

These challenges will become more acute as benchmark interest rates continue to increase and the world moves out of the era of ‘cheap money’. Sub-Saharan African countries are finding it harder to raise debt finance on international capital markets due to prohibitively high interest rates. Shut out of international capital markets, the temptation will increase for sub-Saharan African governments to increase their drawdowns from national savings and stabilization funds to fund their operating expenditures. It is critical that African SWFs continue to maintain their independent governance frameworks, which were carefully developed over the last decade, and remain focused on their long-term goals regarding portfolio allocation and national development strategies.