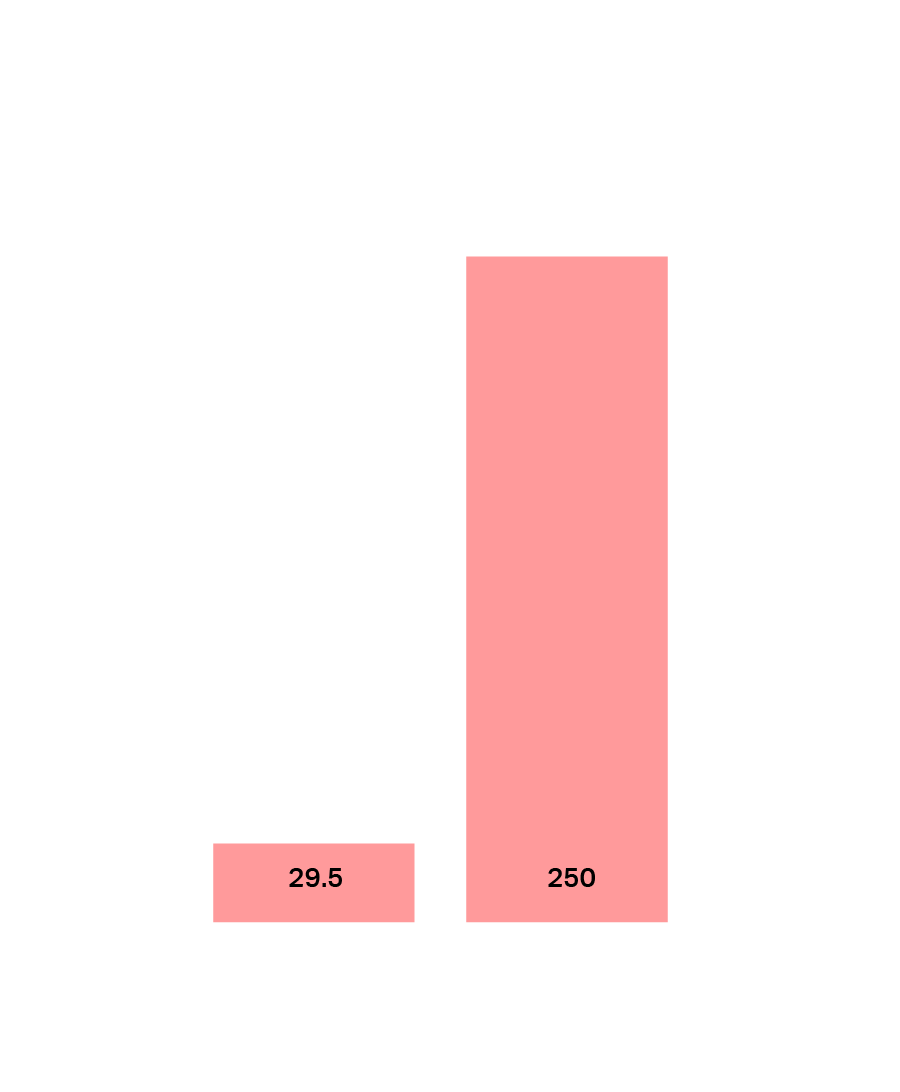

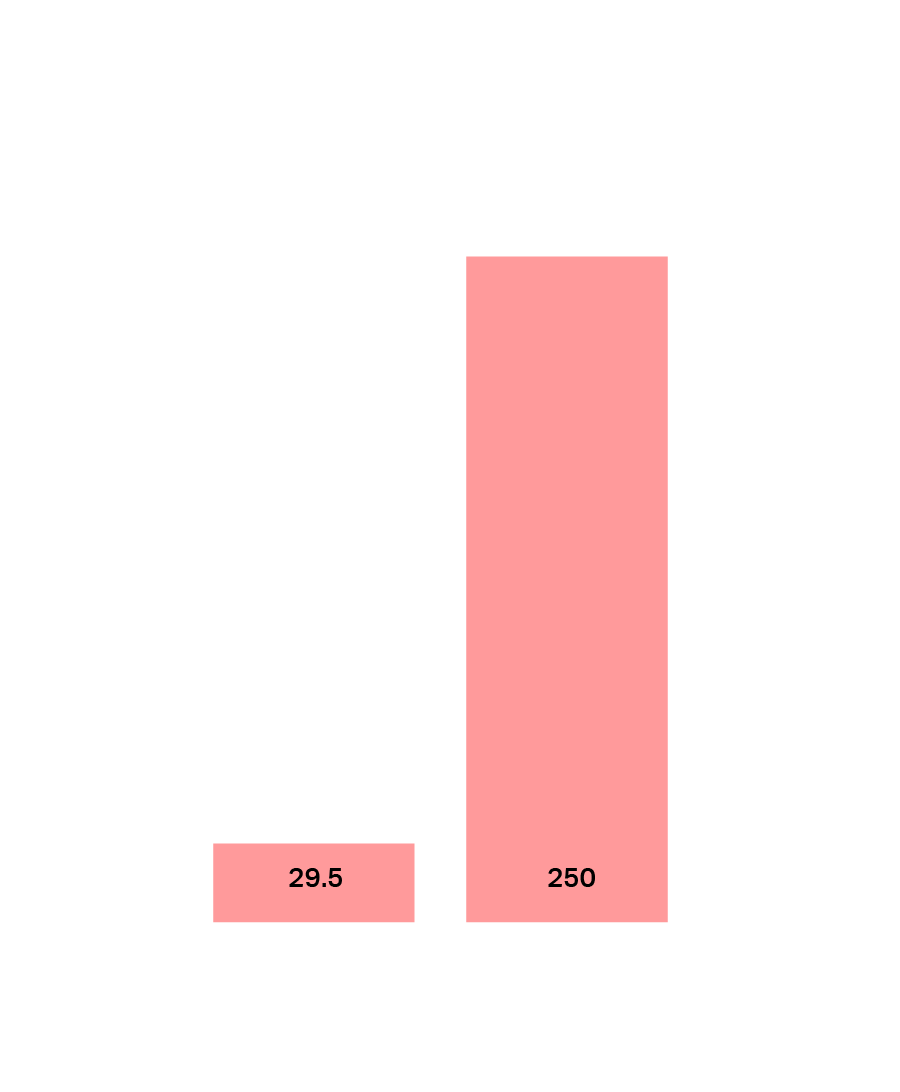

In addition to wide-reaching social and economic development plans to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, African governments are turning their attention to the energy transition, crafting policies and projects to help economies adapt to the impact of climate change. It is estimated that around $250bn is needed annually to help African countries move towards greener technologies and adapt to global warming, while the cost of broader development plans is likely to be much higher. Yet, funding for climate in 2020 was just $29.5bn1.

With domestic budgets constrained and limited tax revenue, international and domestic borrowing remains an essential source of capital. Despite more limited access for some countries to the international Eurobond markets expected in 2023, African governments have a number of options to raise commercial capital, while channels for both concessional and private financing dedicated to sustainable development have opened up.

Eurobond Challenges

Persistently high interest rates, a stronger dollar and tightening global monetary policy all herald challenging market conditions for African issuers looking to raise capital in the public markets in 2023. As well as raising new capital to fund social and economic development projects, African states need to repay about $75bn of medium and long-term external borrowing this year, and a similar amount in 20242.

But African Eurobond yields have risen sharply in secondary markets, suggesting prohibitively high borrowing costs and more difficult access to market-based financing in the year ahead. Nigeria’s Finance Minister Zainab Ahmed, for example, has already said the country has no plans to issue a Eurobond in 2023, unless market conditions improve, because bond prices are too high3. The country will instead turn to concessional loans from development finance institutions, including the World Bank, the Islamic Development Bank and others.

These afflictions are not unique to African sovereigns, however. A growing number of emerging market issuers are struggling with mounting debt loads as inflation and borrowing costs have soared and left them all but locked out of the international capital markets4.In addition, rising interest rates in key economies like the U.S. are diminishing the relative attractiveness of emerging market assets for investors. In October, J.P. Morgan forecast outflows from emerging market bond funds would reach $80bn in 2022 from a previous forecast of $55bn5.

But despite these conditions, African governments have alternative financing options to consider.

International Bank Lending

African governments have begun to explore alternative options to Eurobond markets with syndicated bank loans a key focus. Egypt’s Ministry of Defense signed a $2.5bn five-year syndicated loan with a consortium of 11 banks in November6, Côte d’Ivoire’s Ministry of Economy and Finance raised various loans (from commercial and bilateral creditors) for an aggregate principal amount of XOF 870bn (€1.3bn equivalent) for the development of the Line 1 of the Abidjan subway system in December 20227, while Benin, Madagascar and Senegal, among others, are exploring syndicated loans.

However, access to the international loan market, at reasonable pricing conditions and/or for larger amounts, may require borrowers to seek credit risk mitigation instruments, such as credit risk insurance or guarantees from Export Credit Agencies (ECA)s, development finance institutions or multilateral development banks. Such guarantees from the likes of the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), the African Development Bank, the African Trade Insurance Agency, USAID or GuarantCo can reduce the cost of funding for a borrower as part of the risk is guaranteed by an external party, which in turn increases the appeal of the instrument to a wider range of investors.

Regional Debt Markets

Regional debt markets offer another alternative funding route with developments aimed at improving the liquidity of local markets, making these increasingly viable and liquid options.

South African lender Rand Merchant Bank reports liquidity in the loan market in Africa is strong, in part because a number of loan market deals have not been refinanced, so banks on the continent have excess capital and are actively looking to deploy these funds8.

Nigeria, Egypt and South Africa remain the continent’s most developed domestic markets, but reforms are taking place elsewhere.

Securities regulators in Ghana and Nigeria continue to push for the creation of a regional debt market, mooted in 2021 and due to launch in 2023, in the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) region9. Kenya’s newly elected president William Ruto, for example, has said he plans to introduce domestic dollar denominated bonds to diversify funding sources10.

Sustainable Finance

The rise of ESG investing globally is creating a strong market for financial instruments linked to social or environmental outcomes. The most advanced of these markets is for green bonds, which has already enabled Benin to issue the first ever SDG-linked bond from an African sovereign in 202111. The proceeds of the €500mn 12.5-year deal are being used to finance or refinance green or social eligible expenditures under Benin’s SDG bond framework12. Others are expected to follow, as certain African issuers like Côte d’Ivoire or, more recently, Egypt13 have already published sustainable bonds/loans frameworks which is a necessary step towards the issuance of such sustainable instruments.

One of the current challenges, which needs to be addressed in order to further scale this approach, is the availability of necessary credit enhancement mechanisms to make these transactions qualify as investment grade instruments. Such credit enhancement could be provided by public agencies. Addressing such a critical challenge would further help leverage untapped private investment and resources, which in turn would support these countries’ national development plans and energy transition initiatives and policies at reasonable costs, while yielding sustainable outcomes14.

Innovation in sustainable finance is also offering a number of other channels, including debt linked to nature, which we previously discussed in our recent article, Bringing Nature Into Sovereign Debt15. This includes debt-for-climate and debt-for-nature swaps, in which creditors provide debt relief to governments in return for a commitment to decarbonize their economy or protect biodiverse forests and reefs. While the scalability of such programs, despite investor appetite for sustainable assets, remains to be further tested16, the Seychelles and Belize both reached agreements with creditors in 2018 and 2021 respectively, with the provision of funding contingent on support for natural assets such as biodiversity17.

In September 2022, Barbados issued blue bonds through an innovative liability management transaction. The transaction benefitted from a guarantee from the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the Nature Conservancy (TNC). The proceeds are intended to fund a newly established Barbados Environmental Sustainability Fund, with a purpose to promote marine conservation and sustainable blue economy-related projects18. Situated on one of the most nature rich and biodiverse continents on earth, African countries are well placed to enter such agreements. Gabon for example, is in talks to swap $700mn in Eurobonds with the Nature Conservancy to fund marine conservation19, as well as to raise $200mn in green bonds to fund hydro-dams, according to Bloomberg20.

Structural Reforms to Improve Access to Capital

Liquidity and Sustainability Facility

Substantial efforts have been made to improve the liquidity of African sovereign Eurobonds, including the launch of a Liquidity and Sustainability Facility (LSF) which will allow investors to use African debt issued in foreign currencies like euros and dollars in repo transactions. The United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), which designed the facility along with the African Export-Import Bank (Afreximbank), announced the conclusion of the facility’s first transaction at COP27 in Egypt21.

The $100mn transaction, arranged with Citi, is aimed at supporting UNECA’s twin objectives of improving the liquidity of African Eurobonds and incentivizing SDG-related investments like sustainable and green bonds. UNECA estimates the facility will save $11bn in interest costs over the next five years22.

Resilience and Sustainability Facility

The IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF) is another initiative aimed at helping low-income and vulnerable middle-income countries to address longer-term challenges, including those related to climate change and pandemic preparedness.

Rwanda is the first African country to have accessed the newly-created facility, having secured $319mn of equivalent funding under the RSF in December 2022. The program will support Rwanda’s efforts to build resilience to climate change23.

Multilateral Development Bank (MDBs) Reform

Despite such initiatives, MDBs remain under pressure to increase their lending to developing countries with major economies like the U.S. and Germany calling for a fundamental overhaul of the World Bank and other global financial institutions24.

Developed countries are yet to meet their 2009 pledge to mobilize $100bn per year by 2020 in climate finance to emerging countries while the promise of blended finance, which aimed to catalyze billions of dollars of private sector funding, has not delivered25. Providing guarantee instruments to sovereign issuers would help reduce the perceived risk and thus the borrowing costs, which in turn would create a much-needed fiscal space for these countries.

As 2023 begins, African nations might be finding themselves with limited access to international capital markets, but as we have discussed in this article, there is clearly a range of alternative options to turn to, as they try raise capital while continuing to transition to greener, cleaner economies.

Barthélemy Faye

Partner

Paris

T: +33 1 40 74 68 00

bfaye@cgsh.com

V-Card

Christophe Wauters

Counsel

Brussels

T: +32 22872198

chwauters@cgsh.com

V-Card

Pap Diouf

Associate