In August, Nigeria unveiled an ambitious new energy transition plan which aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2060, and mobilize significant investment in renewable forms of energy1. The plan is part of a continent-wide green energy transition as countries look to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels, in accordance with Paris Agreement targets.

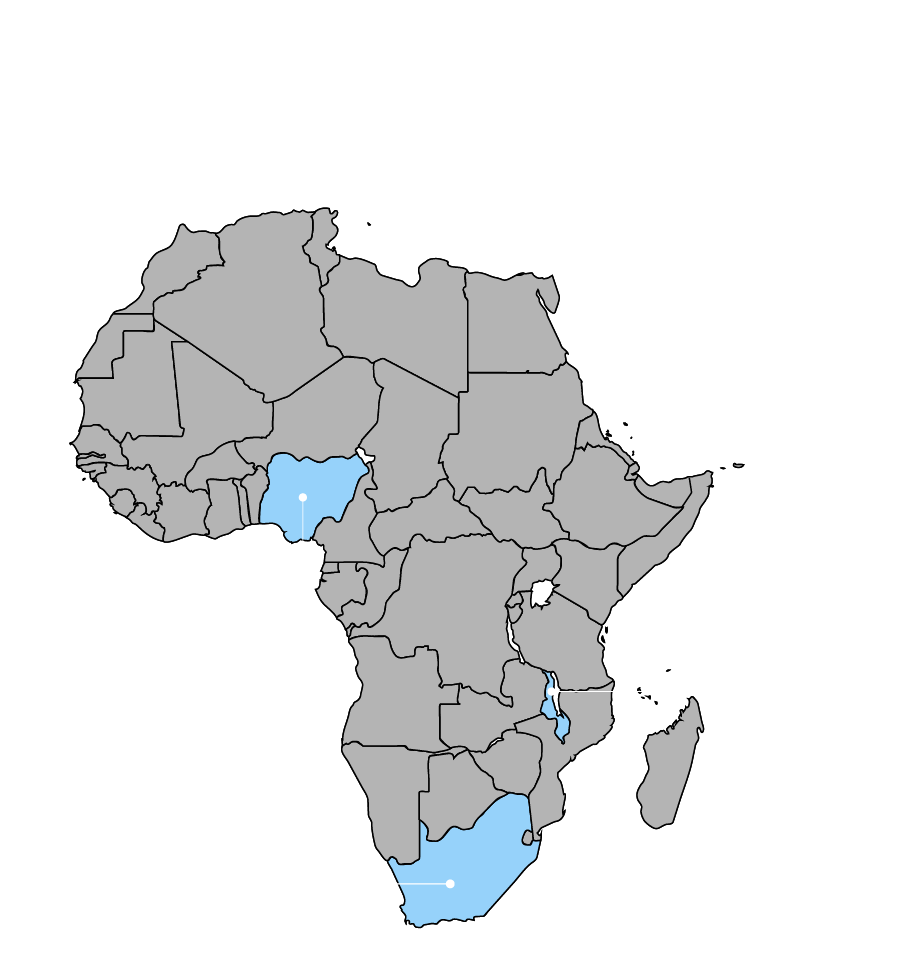

Just three African countries – South Africa, Nigeria and Malawi – have set net zero targets so far, reflecting the challenge of accelerating universal energy access and an energy transition without compromising development objectives. However, African states are increasingly enacting environmental legislation and signing onto international agreements for the environment. Of the 195 signatories of the Paris Agreement, 45 are African states, representing over 80% of all African countries2.

While the energy transition is a huge investment opportunity – Nigeria says it needs $410bn to deliver its plan by 20603, for example – it also brings huge uncertainty. Particularly concerned are those with existing investments in fossil fuel industries, as governments pass laws and regulations to facilitate the transition and to phase down and out legacy fossil fuel infrastructure.

Natural resources in African countries tend to be owned by the state and as such, energy projects often require investors to contract directly with the local governments. As a result, any changes to laws prompted by the energy transition may leave African governments vulnerable to investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) under multilateral or bilateral investment treaties, in the event that foreign investors commence arbitration proceedings alleging that government regulatory changes breach the protections afforded to investors under those treaties.

In August, Nigeria unveiled an ambitious new energy transition plan which aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2060, and mobilize significant investment in renewable forms of energy1. The plan is part of a continent-wide green energy transition as countries look to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels, in accordance with Paris Agreement targets.

Just three African countries – South Africa, Nigeria and Malawi – have set net zero targets so far, reflecting the challenge of accelerating universal energy access and an energy transition without compromising development objectives. However, African states are increasingly enacting environmental legislation and signing onto international agreements for the environment. Of the 195 signatories of the Paris Agreement, 45 are African states, representing over 80% of all African countries2.

While the energy transition is a huge investment opportunity – Nigeria says it needs $410bn to deliver its plan by 20603, for example – it also brings huge uncertainty. Particularly concerned are those with existing investments in fossil fuel industries, as governments pass laws and regulations to facilitate the transition and to phase down and out legacy fossil fuel infrastructure.

Natural resources in African countries tend to be owned by the state and as such, energy projects often require investors to contract directly with the local governments. As a result, any changes to laws prompted by the energy transition may leave African governments vulnerable to investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) under multilateral or bilateral investment treaties, in the event that foreign investors commence arbitration proceedings alleging that government regulatory changes breach the protections afforded to investors under those treaties.

Disputes on the Rise

Many African governments signed Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) from the 1990s onwards, granting broad rights to international investors in a bid to attract much needed foreign direct investment. However, these treaties put African states at risk of ISDS claims by investors. There are 893 bilateral investment treaties currently in force across the African continent, including North Africa, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development’s Investment Policy Hub BIT tracker4.

Other multilateral treaties like the 2003 Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Energy Protocol also provide the basis for ISDS. The ECOWAS Energy Protocol was informed by the multilateral Energy Charter Treaty, and provides protection to energy investors in the ECOWAS region, including the right to commence ISDS. A total of 13 out of 15 ECOWAS member states have ratified the Energy Protocol which as a result has now entered into force, meaning investors can now use the investment protections it offers.

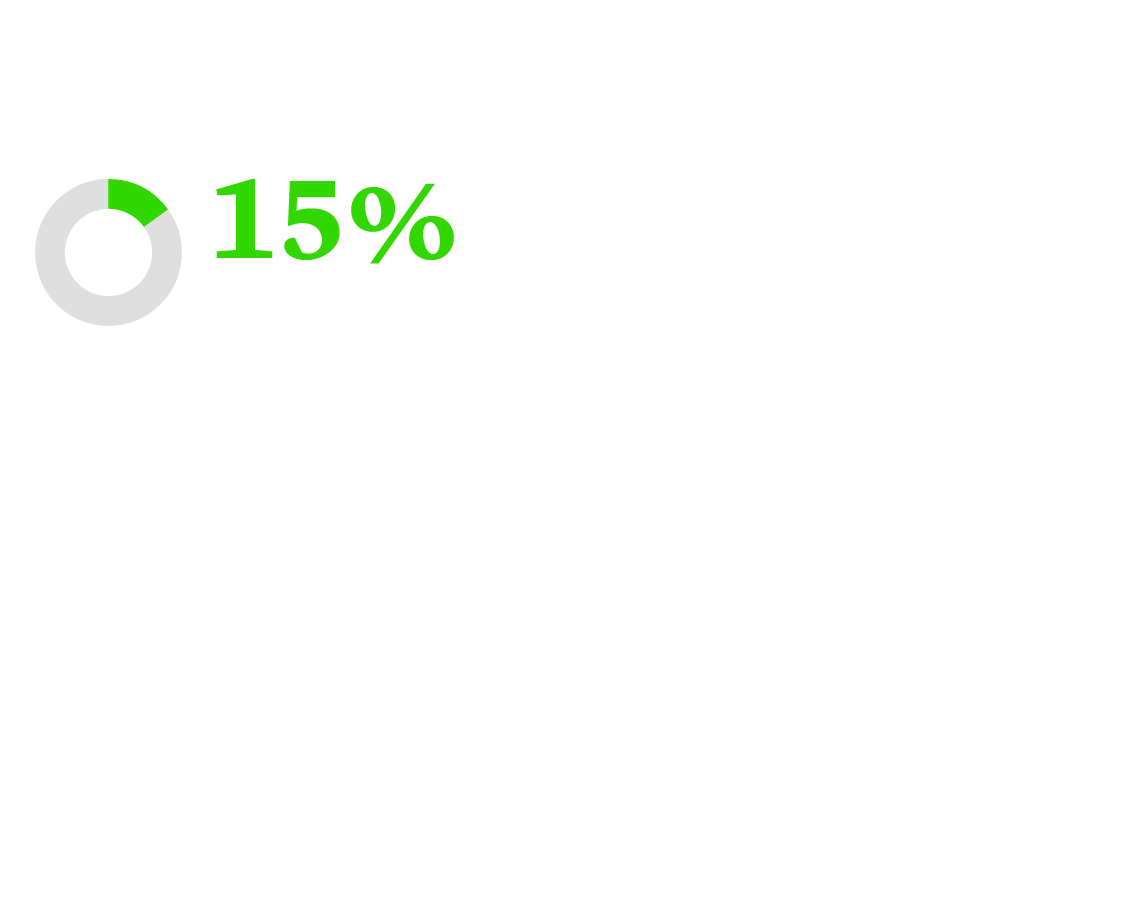

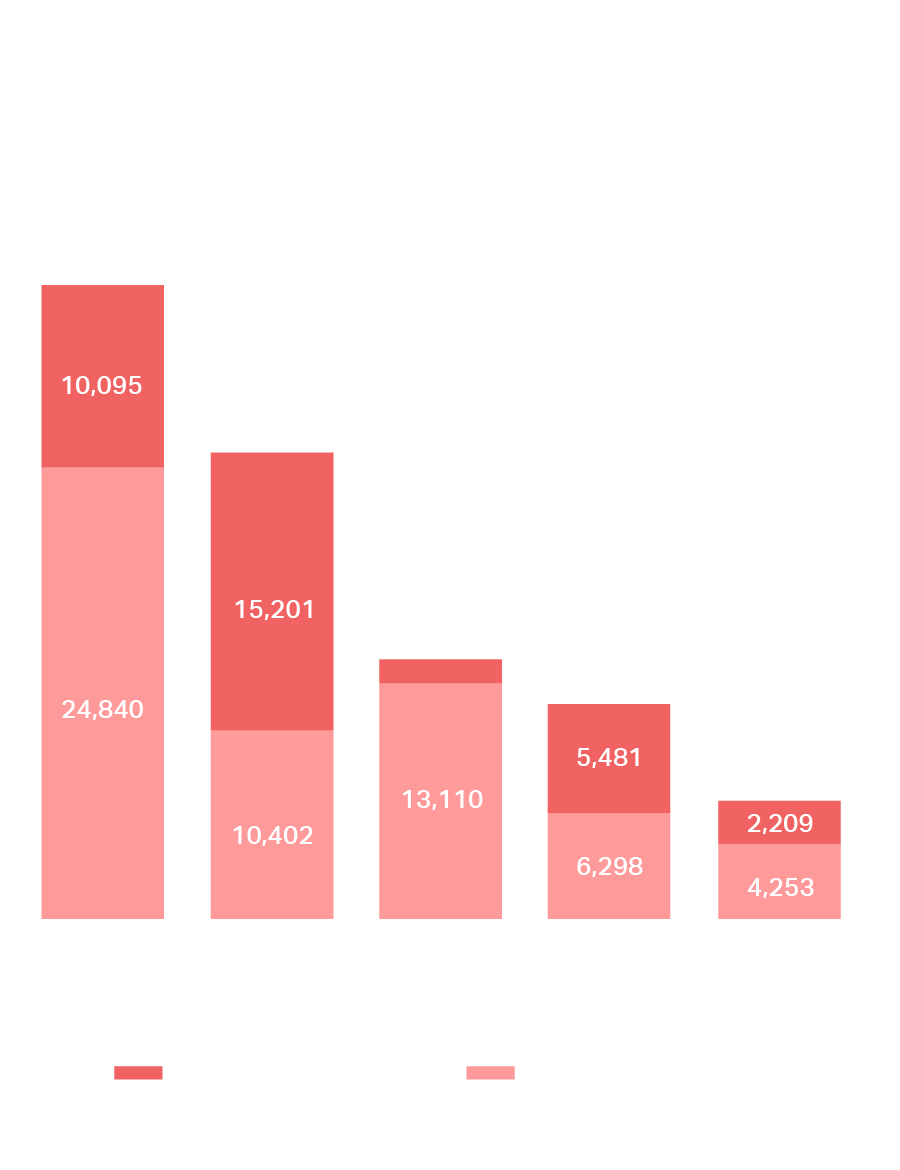

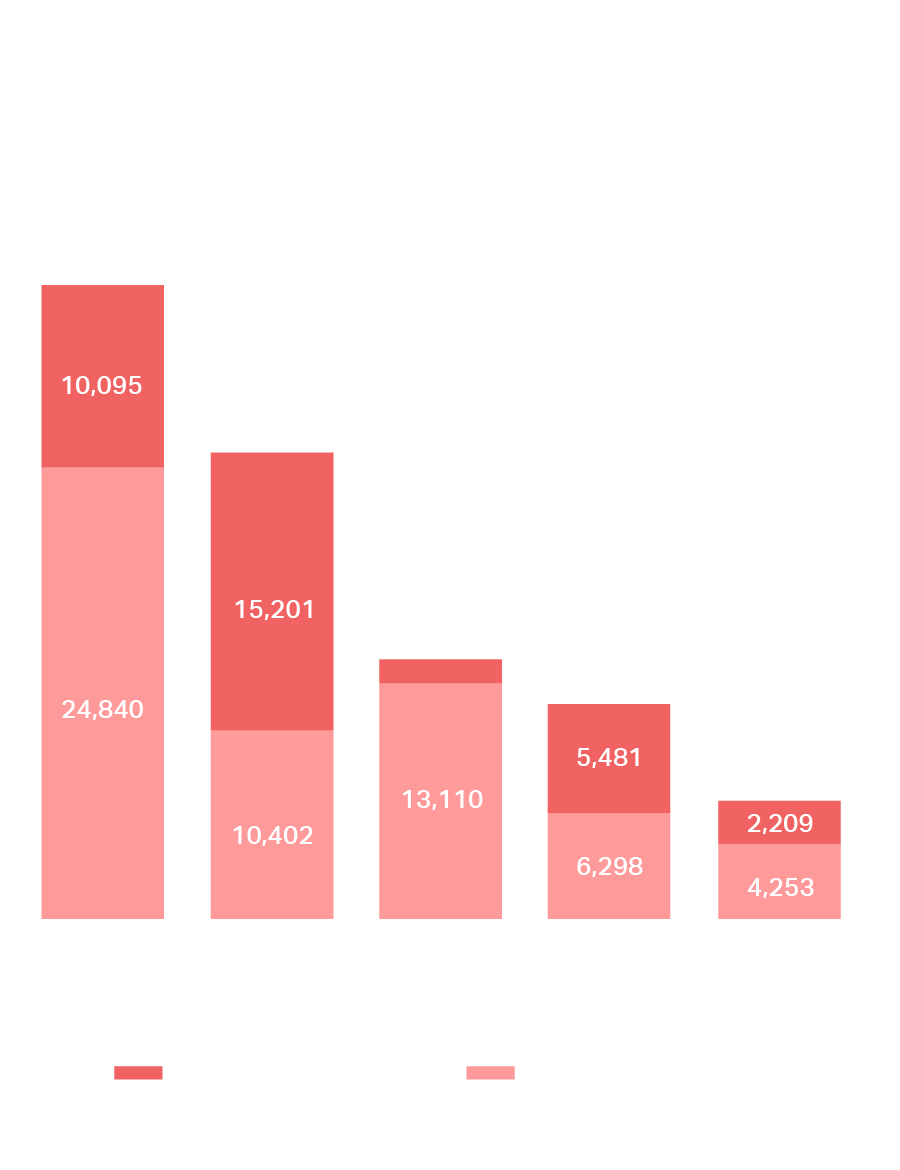

Sub-Saharan Africa has accounted for 15% of all cases registered under the ICSID Convention and Additional Facility rules between 1966 and 2022, and 12% of new cases in the fiscal year 2022. This amounted to six cases in total, according to ICSID, with two against the Republic of the Congo, two against Mali and one against each of Senegal and the Republic of Sudan5. In 2021, there were eight African states involved in ICSID proceedings6.

Types of Claims

While the many claims brought against EU countries by investors relate to fossil fuel phase-outs, on the African continent, the primary drivers at this stage are more likely to be driven by changes to renewable energy frameworks or resource nationalism.

With natural resources such as wind and sun abundant, renewables are a mainstay of the green energy transition across the African continent. So far, the sector has attracted more than $55bn in investment from 2010 until 2020, with solar investment leading this trend and reaching $5.2bn in 2018 alone – but it requires much more7. Drastic policy changes in the renewables sector which risk devaluing investments or violating legitimate expectations are a potential dispute risk.

As an example, German renewables company Frazer Solar successfully pursued arbitration against the African state of Lesotho after the state backed out of a contract to acquire renewable energy assets8. WaIAm Energy LLC v. Republic of Kenya offers a further example. In this ICSID arbitration, the Canada-based claimant alleged that Kenya had improperly terminated its license to explore and develop a geothermal project. This time however, the tribunal held in the state’s favour, finding that the termination of the underlying contract was valid given that the claimant had not fulfilled its work obligations under the contract9.

In the mining sector, also crucial to the renewable transition, dispute risks may arise in response to resource nationalism. Minerals abundant in various African countries such as lithium are increasingly essential to the global energy transition by helping to power electric vehicles. This may prompt changes to regulatory frameworks or the imposition of windfall taxes on investee companies in an attempt to limit or control foreign ownership of domestic resources, which in turn may prompt investment claims.

Carbon Market Risks

Many African states are responding to rising global demand for carbon offsets in both the voluntary and compliance carbon markets by developing large carbon credits projects. Earlier this month Gabon unveiled plans to sell 90 million carbon credits in the voluntary carbon markets ahead of COP2710. Seen by many developing states as a lucrative revenue stream – and by more economically developed countries and companies as an essential tool for meeting both voluntary and mandatory carbon emissions reductions targets – the high level of investment and expected regulatory changes are likely to lead to related claims.

It is possible that government regulation or intervention in carbon offset projects may lead to investor-state arbitration claims against states under applicable investment treaties, where investments in such carbon offset projects are foreign-owned.

In particular, indirect expropriation claims, or legitimate expectation claims could arise where a corporate alleges that government legislative changes are arbitrary, unreasonable, discriminatory and/or strip them of the value of the project or breached their legitimate investment-backed expectations. This could be a particular issue if guarantees were made when the corporate first participated in offset schemes.

What States Are Doing to Protect Themselves

Several African states are taking measures to protect themselves from investment claims. This may include terminating bilateral investment treaties outright – for example, in 2018 Tanzania issued a notice of intent to terminate the Netherlands-Tanzania BIT on the basis that the treaty impeded Tanzania’s ability to regulate investments in the public interest. However, even where BITs are terminated, claims may still arise where the BITs contain ‘sunset clauses’ protecting historic investments made prior to termination.

Countries are also entering into investment treaties that aim to take stock of their changing context. The Morocco-Nigeria BIT, for example, requires investors to conduct social impact assessments and comply with environmental assessment screening, as well as ensure investors meet or exceed national and internally accepted standards of corporate governance, such as the 2012 Model BIT of the Southern African Development Community (SADC)11.

More generally, African governments are beginning to introduce environmental protection language to protect their discretion in environmental matters. This takes the form of specific provisions for the promotion and protection of the environment, as well as provisions that create exceptions for state measures in accordance with environmental legislation and international agreements. Such clauses can be seen in BITs from Madagascar, Mali, Morocco, and Tanzania12. This will help them balance obligations to foreign investors with the need to protect the environment.

Limited practice regarding how environmental protection language in treaties will be interpreted makes it difficult to ascertain how such amendments may affect claims. As the energy transition gathers pace across Africa, similar disputes are almost certainly likely to arise, though the direction of their resolution is as of yet unclear.

What States Are Doing to Protect Themselves

Several African states are taking measures to protect themselves from investment claims. This may include terminating bilateral investment treaties outright – for example, in 2018 Tanzania issued a notice of intent to terminate the Netherlands-Tanzania BIT on the basis that the treaty impeded Tanzania’s ability to regulate investments in the public interest. However, even where BITs are terminated, claims may still arise where the BITs contain ‘sunset clauses’ protecting historic investments made prior to termination.

Countries are also entering into investment treaties that aim to take stock of their changing context. The Morocco-Nigeria BIT, for example, requires investors to conduct social impact assessments and comply with environmental assessment screening, as well as ensure investors meet or exceed national and internally accepted standards of corporate governance, such as the 2012 Model BIT of the Southern African Development Community (SADC)11.

More generally, African governments are beginning to introduce environmental protection language to protect their discretion in environmental matters. This takes the form of specific provisions for the promotion and protection of the environment, as well as provisions that create exceptions for state measures in accordance with environmental legislation and international agreements. Such clauses can be seen in BITs from Madagascar, Mali, Morocco, and Tanzania12. This will help them balance obligations to foreign investors with the need to protect the environment.

Limited practice regarding how environmental protection language in treaties will be interpreted makes it difficult to ascertain how such amendments may affect claims. As the energy transition gathers pace across Africa, similar disputes are almost certainly likely to arise, though the direction of their resolution is as of yet unclear.

Christopher P. Moore

Partner

London

T: +44 20 7614 2227

New York

T: +1 212 225 2836

cmoore@cgsh.com

V-Card

Laurie Achtouk‑Spivak

Counsel

Paris

T: +33 1 40 74 68 00

lachtoukspivak@cgsh.com

V-Card

Naomi Tarawali

Associate

London

T: +44 20 7614 2304

ntarawali@cgsh.com

V-Card

Robert Garden

Associate