Collective Action Clauses (CACs) have come into focus over the past year in the context of sovereign debt restructurings. Ecuador’s successful debt restructuring resulted in the first-ever ruling by a New York court on use of the 2014 ICMA-based Collective Action Clauses (CACs) in a sovereign debt restructuring. More recently, New York state legislators proposed legislation that would, among other things, retroactively insert CACs into all sovereign bonds governed by New York law. With CACs back in the spotlight, this note discusses their evolution and effectiveness, and potential to catalyse orderly sovereign debt restructurings going forward.

CACs Protect Creditors, Not Just Debtors

When a sovereign defaults on its debt, that event can have negative consequences for the lives of its people and can create ripples across the regional, or even global economy. Sovereign debt restructuring techniques are keenly important in limiting these adverse consequences.

Under standard New York law documentation, restructuring sovereign bonds typically required 100% creditor-approval for any change in the financial terms to take place. This means that a single bondholder can hold out and prevent a restructuring from reaching completion. As Argentina’s long battle with holdout creditors following its 2005 and 2010 exchange offers shows, even a restructuring that is appealing to the vast majority of creditors may be frustrated by determined holdouts seeking to extract more value than their peers, at any cost. Minority creditors might also try to halt a restructuring that has majority backing, creating uncertainty and delay that the majority creditor group faces alongside the sovereign.

Although a small number of countries, including the UK and Belgium, have passed domestic laws attempting to address this issue of sovereign creditor holdouts, their effectiveness is limited by the international nature of sovereign debt. Without an international bankruptcy code in place, the need for a tool that would allow majority creditors to bring along their peers became clear. Enter CACs—which allow sovereign bonds’ main terms to be amended by agreement of a creditor-supermajority, making debt restructurings binding on a minority of dissenting creditors.

A Brief History of CACs

From a legal perspective, sovereign borrowing became an entirely different game in the late 1970s. The traditional consensus that sovereigns were immune from judicial enforcement by private creditors was abandoned. In the 1980s, bank loan debt was exchanged for highly liquid bond debt, which added a wide universe of private investors to the supply of capital for developing countries, exposing sovereign borrowers to a new world of market risk.

Compared with commercial banks, bondholders are harder to coordinate in restructuring negotiations, and private investors of this kind are not shy about using litigation to try and exert pressure against sovereigns. As a result, courts charged with deciding legal issues related to sovereign debt can play a crucial role in determining the outcome of disputes surrounding a restructuring, whether between debtor and bondholders or between bondholders with divergent interests or preferences.

Discussions around using CACs to facilitate sovereign debt restructurings began in 1995. Mexico incorporated CACs into its New York-law bond documentation in 2003, and their use became widespread soon afterwards, including the “dual-limb” aggregation feature introduced by Uruguay in 2003.

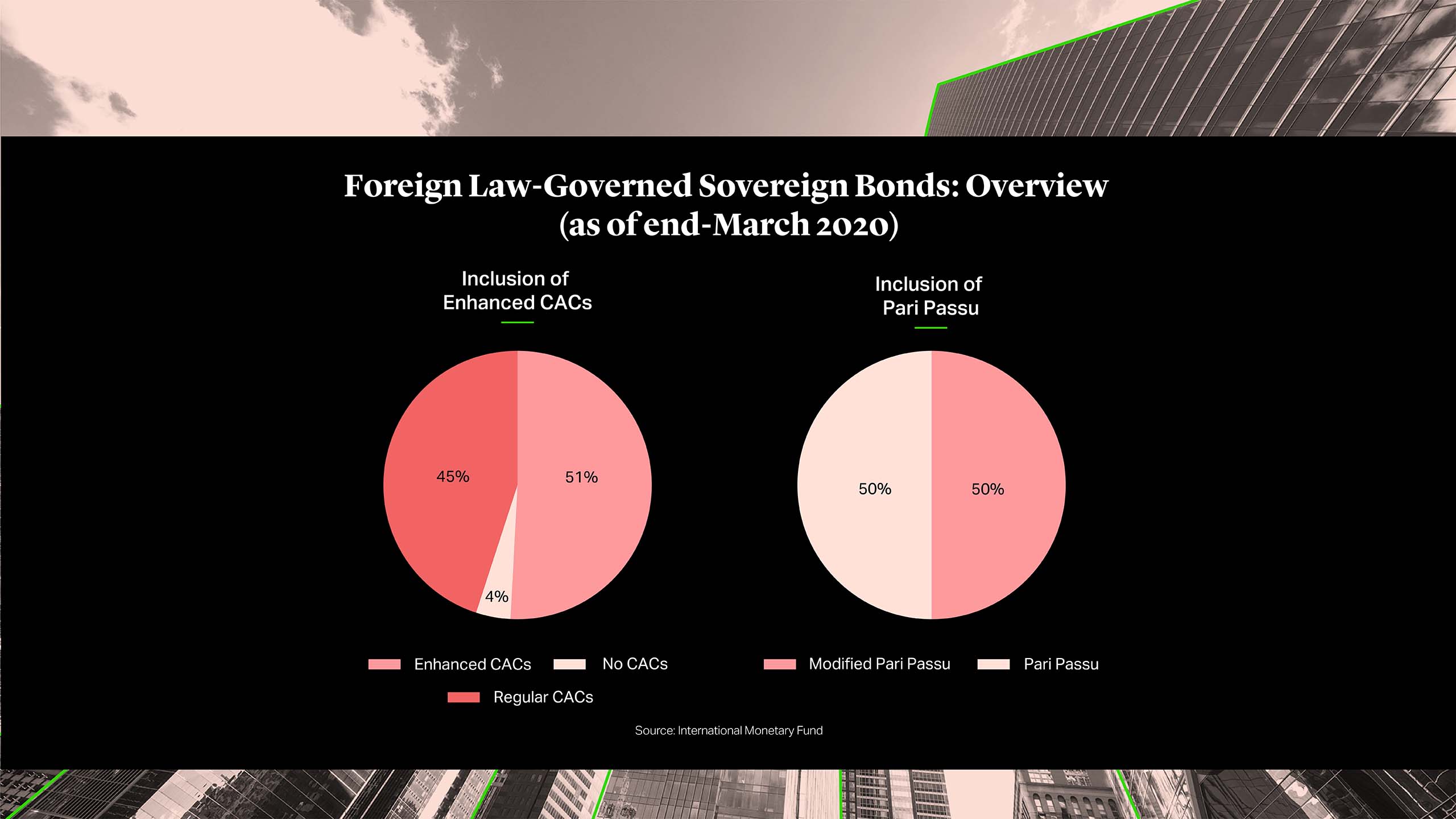

A decade later, in cases against Argentina, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit highlighted the potential of CACs to advance sovereign debt restructurings. In interpreting the so-called “pari passu” clause (a contractual provision found widely in sovereign debt contracts regarding equal treatment of creditors), the court ruled that Argentina could not service its restructured debt unless it made rateable payments to holdout creditors who had refused to participate in the restructuring. The court noted, though, that such holdout problems could be mitigated in other cases through CACs.

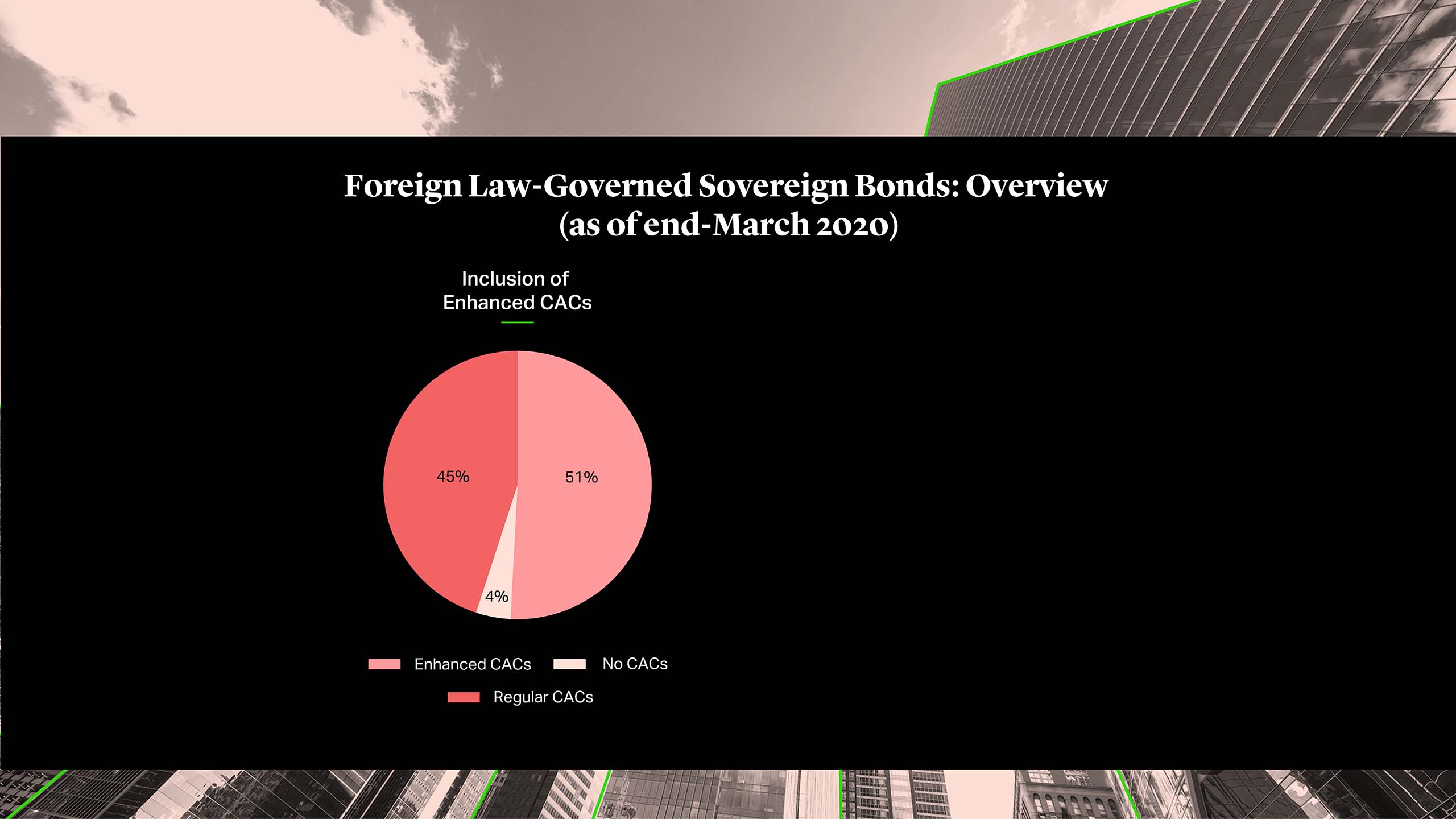

That same year, the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) released an ‘enhanced CAC’ which was endorsed by the IMF and G20. Among other features, this enhanced clause allowed for an ‘aggregation’, or combination of multiple bond series under a ‘single limb’ clause, meaning creditors holding very dissimilar instruments could potentially be crammed into a restructuring only based on the aggregate vote, without acceptance of any required percentage vote of the holders of any a single instrument.

A Brief History of CACs

From a legal perspective, sovereign borrowing became an entirely different game in the late 1970s. The traditional consensus that sovereigns were immune from judicial enforcement by private creditors was abandoned. In the 1980s, bank loan debt was exchanged for highly liquid bond debt, which added a wide universe of private investors to the supply of capital for developing countries, exposing sovereign borrowers to a new world of market risk.

Compared with commercial banks, bondholders are harder to coordinate in restructuring negotiations, and private investors of this kind are not shy about using litigation to try and exert pressure against sovereigns. As a result, courts charged with deciding legal issues related to sovereign debt can play a crucial role in determining the outcome of disputes surrounding a restructuring, whether between debtor and bondholders or between bondholders with divergent interests or preferences.

Discussions around using CACs to facilitate sovereign debt restructurings began in 1995. Mexico incorporated CACs into its New York-law bond documentation in 2003, and their use became widespread soon afterwards, including the “dual-limb” aggregation feature introduced by Uruguay in 2003.

A decade later, in cases against Argentina, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit highlighted the potential of CACs to advance sovereign debt restructurings. In interpreting the so-called “pari passu” clause (a contractual provision found widely in sovereign debt contracts regarding equal treatment of creditors), the court ruled that Argentina could not service its restructured debt unless it made rateable payments to holdout creditors who had refused to participate in the restructuring. The court noted, though, that such holdout problems could be mitigated in other cases through CACs.

That same year, the International Capital Market Association (ICMA) released an ‘enhanced CAC’ which was endorsed by the IMF and G20. Among other features, this enhanced clause allowed for an ‘aggregation’, or combination of multiple bond series under a ‘single limb’ clause, meaning creditors holding very dissimilar instruments could potentially be crammed into a restructuring only based on the aggregate vote, without acceptance of any required percentage vote of the holders of any a single instrument.

A Victory for CACs in Ecuador’s Restructuring

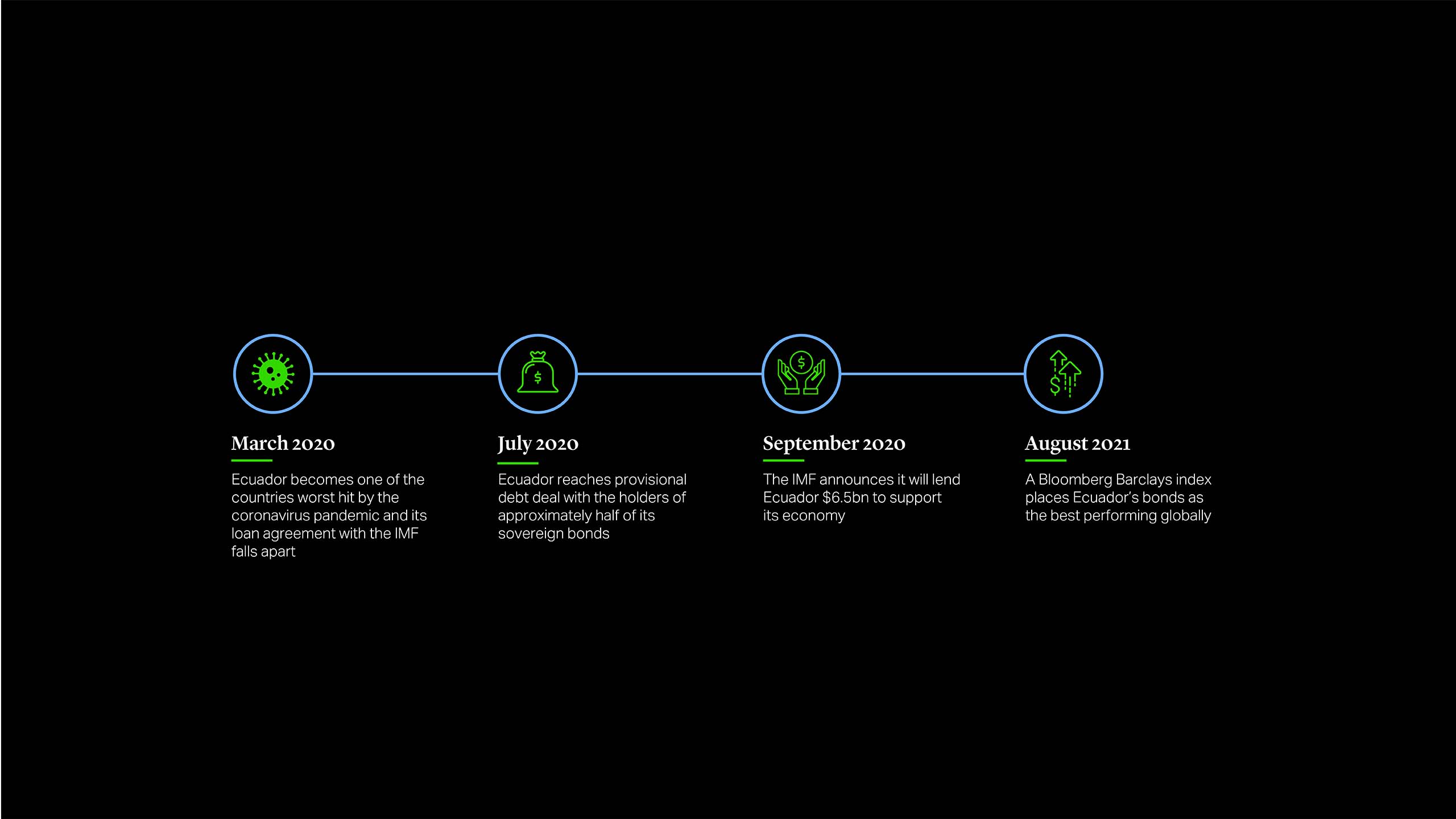

The first test of the ICMA CACs’ newest features and their ability to protect creditors’ interests against minority holdouts came last year, just before Ecuador’s successful $17.4bn debt restructuring closed1.

Facing a severe economic crisis brought on by the COVID-19 global pandemic and an unprecedented drop in oil prices, Ecuador made a debt restructuring proposal to its creditors. Creditors were invited to consent to modification of the terms of their bonds and to exchange them for new, performing bonds to be issued by Ecuador.

Ecuador’s proposal gained the support of the requisite majorities of consenting bondholders. However, a minority bondholder group filed a case seeking a temporary restraining order and a preliminary injunction that would prevent the restructuring from going forward. The bondholder plaintiffs claimed Ecuador had committed securities fraud by saying in a press release that the proposed restructuring was fair and permissible under the terms of the bond documents, when—according to the plaintiffs—the restructuring was in fact coercive and exceeded the limits of the contract.

After two days of expedited briefing and court hearings, Judge Valerie Caproni of the district court for the Southern District of New York rejected the plaintiffs’ arguments. The statements in Ecuador’s press release could not amount to securities fraud, the court ruled, because they were not “indisputably false”. The court went as far as to say that the statements were not false because the proposed restructuring was permitted under the CACs and all bondholders were presented with the same offer.

Conclusion

The Ecuador ruling showed that CACs can be a useful mechanism to overcome holdouts and complete debt restructurings approved by requisite creditor majorities. The dispute was decided on a specific set of facts, however, and it remains to be seen how watertight even the ‘enhanced’ CAC will be against creative and determined opposition.

That said, in the absence of an international bankruptcy framework, CACs have emerged as the most effective mechanism available for sovereign debt restructurings, with the potential to protect not only sovereigns but also creditors with conflicting interests.

Carmine D. Boccuzzi Jr.

Partner

New York

T: +1 212 225 2508

cboccuzzi@cgsh.com

V-Card

Ignacio Lagos

Associate

New York

T: +1 212 225 2852

ilagos@cgsh.com

V-Card

Rathna Ramamurthi

Associate