Carbon credit markets have emerged over the past few years as a tool in the fight against climate change. They allow companies, governments, and individuals to offset their carbon emissions by buying credits that represent reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. A carbon credit represents one metric ton of carbon dioxide and is created via projects that reduce or capture emissions, such as reforestation, renewable energy or carbon capture and storage.

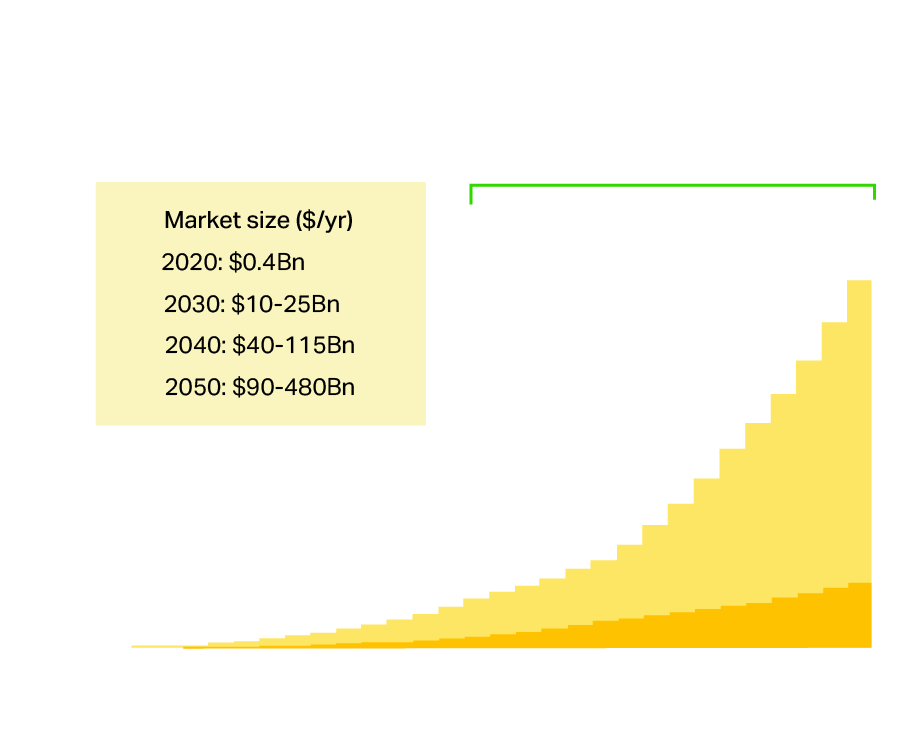

The size of the carbon credit market is difficult to measure as the value is linked to the perceived quality of the issuing company. At the moment, it is a diverse set of systems that are regulated in different jurisdictions to trade greenhouse gas pollution rights.

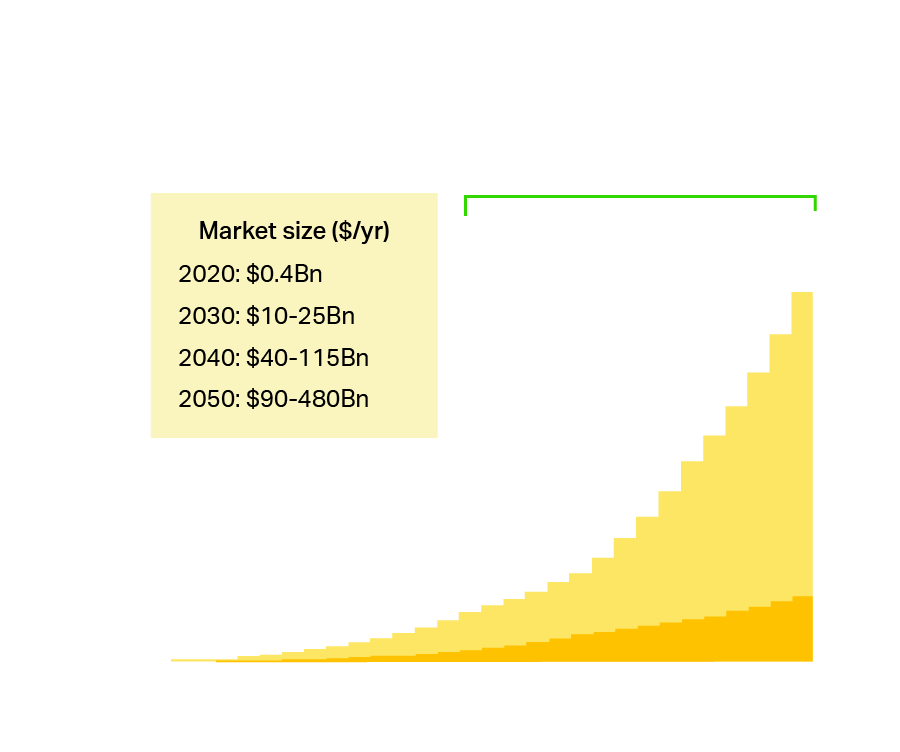

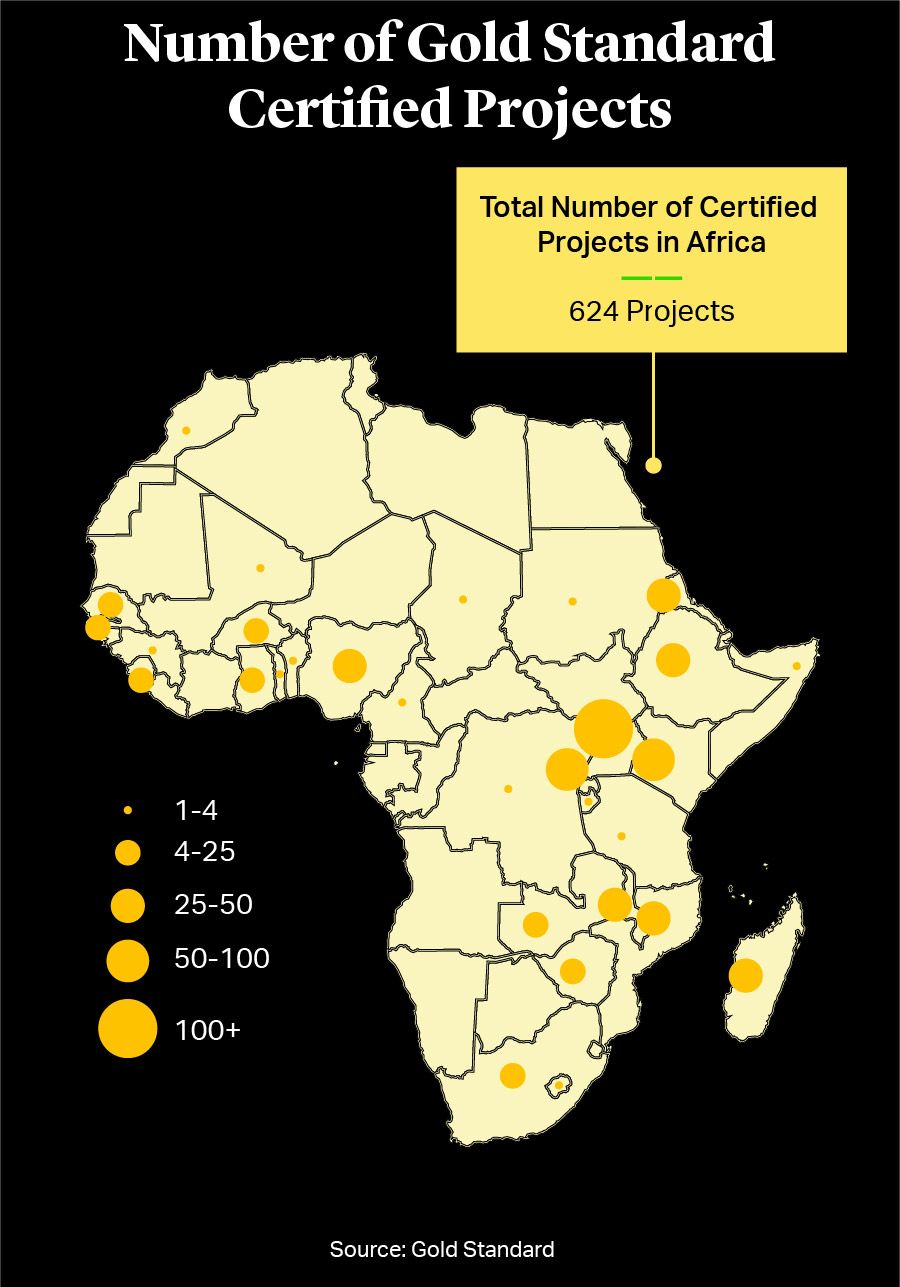

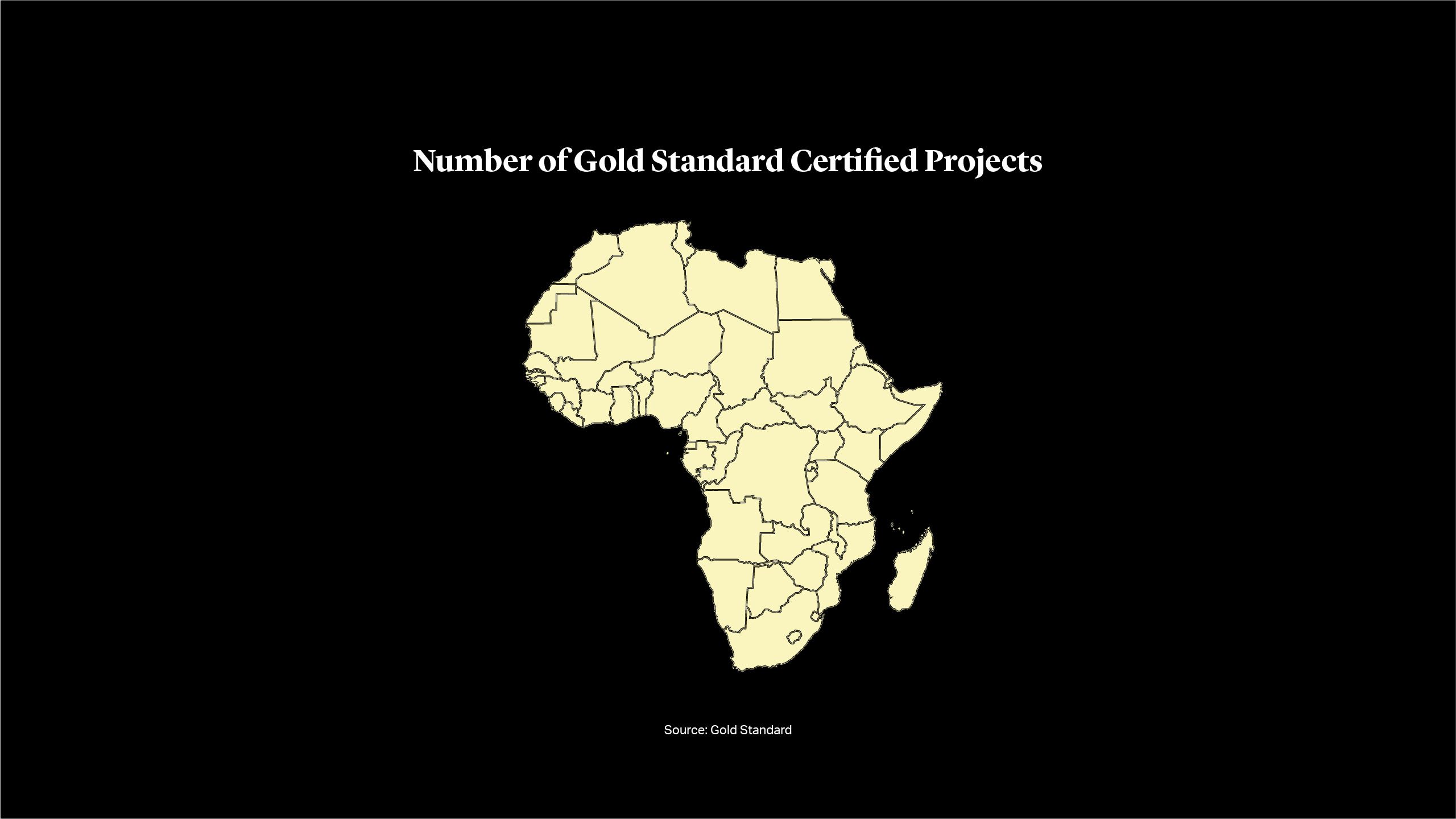

Despite questions about regulation, the market is expected to grow from around $400mn in 2020 to up to $25bn by 20301. Africa has been lagging behind its peers in this market to date. Only 11% of global carbon credits issued globally between 2016 and 2021 came from African countries based on 624 projects, according to Geneva-based non-profit Gold Standard2. Meanwhile, the Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis estimates that only 2% of the continent’s maximum annual capacity for carbon credits has been tapped3 – compare this to Latin America which already generates around 20% of all global carbon credits4.

Carbon credit markets have emerged over the past few years as a tool in the fight against climate change. They allow companies, governments, and individuals to offset their carbon emissions by buying credits that represent reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. A carbon credit represents one metric ton of carbon dioxide and is created via projects that reduce or capture emissions, such as reforestation, renewable energy or carbon capture and storage.

The size of the carbon credit market is difficult to measure as the value is linked to the perceived quality of the issuing company. At the moment, it is a diverse set of systems that are regulated in different jurisdictions to trade greenhouse gas pollution rights.

Despite questions about regulation, the market is expected to grow from around $400mn in 2020 to up to $25bn by 20301. Africa has been lagging behind its peers in this market to date. Only 11% of global carbon credits issued globally between 2016 and 2021 came from African countries based on 624 projects, according to Geneva-based non-profit Gold Standard2. Meanwhile, the Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis estimates that only 2% of the continent’s maximum annual capacity for carbon credits has been tapped3 – compare this to Latin America which already generates around 20% of all global carbon credits4.

Funding via the carbon markets could help address two major issues facing African nations. First, it can contribute to the fight against climate change and help countries achieve their sustainable development goals. Second, the carbon markets could deliver much-needed revenues to governments across the continent and further help uplift vulnerable communities. Independent shared value calculations show that projects that issue carbon credits are already making a difference and have led to an estimated $16bn worth of co-benefit when factors like positive impacts on biodiversity, employment, and the livelihood of target communities are taken into account5.

Historically, African markets have been perceived as less sophisticated with limited opportunities. As for the carbon credit market development, this perception may partly have been sustained by a lack of political will and awareness about the opportunities and potential of the continent’s carbon credit market. This is changing, however, as recognition grows about the opportunities it offers. A notable line in the sand was drawn in June 2023 when the world’s largest carbon market auction was held in Nairobi. More than 2.2 million tons of carbon credits were sold to both regional and international companies6. The projects related to the Nairobi auction were a mixture of emission avoidance and removal and included a variety of schemes such as renewable energy projects in Egypt and South Africa, as well as the supply of improved clean cookstoves to communities in Kenya and Rwanda.

Funding via the carbon markets could help address two major issues facing African nations. First, it can contribute to the fight against climate change and help countries achieve their sustainable development goals. Second, the carbon markets could deliver much-needed revenues to governments across the continent and further help uplift vulnerable communities. Independent shared value calculations show that projects that issue carbon credits are already making a difference and have led to an estimated $16bn worth of co-benefit when factors like positive impacts on biodiversity, employment, and the livelihood of target communities are taken into account5.

Historically, African markets have been perceived as less sophisticated with limited opportunities. As for the carbon credit market development, this perception may partly have been sustained by a lack of political will and awareness about the opportunities and potential of the continent’s carbon credit market. This is changing, however, as recognition grows about the opportunities it offers. A notable line in the sand was drawn in June 2023 when the world’s largest carbon market auction was held in Nairobi. More than 2.2 million tons of carbon credits were sold to both regional and international companies6. The projects related to the Nairobi auction were a mixture of emission avoidance and removal and included a variety of schemes such as renewable energy projects in Egypt and South Africa, as well as the supply of improved clean cookstoves to communities in Kenya and Rwanda.

Current Initiatives in Africa

Carbon markets are likely to expand as African governments like Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe begin to look at regulation of the carbon market to help support projects that will address their development needs, bridge the economic and social infrastructure gap, and benefit local communities.

At the beginning of December 2023, for example, Tanzania inked a deal for one of East Africa’s largest carbon credit projects that covers all six of its national parks – some 1.8 million hectares7. The sale was managed by Tanapa, the country’s national park management agency, and Carbon Tanzania with revenues going to local communities.

Much of the impetus has been given by the World Bank which has been an early supporter of a number of projects across the continent8. One of the first was a vehicle scrapping and recycling project in Egypt which has led to replacing over 40,000 old taxis in Cairo alone and helped avoid the equivalent of 130,000 tons of carbon dioxide within its first year. Not only has the new taxi fleet reduced emissions of a range of airborne pollutants, but it also contributed to increased traffic safety across the country.

Another project has been increasing the reach of the Olkaria II geothermal project in Kenya. The Unit 3 Geothermal Expansion Project has added a third 35 megawatt generator, which adds around 276 gigawatts of electricity to the Kenyan national grid. This has helped the project to issue over 230,000 carbon credits in its first year.

At the beginning of December 2023, for example, Tanzania inked a deal for one of East Africa’s largest carbon credit projects that covers all six of its national parks – some 1.8 million hectares7. The sale was managed by Tanapa, the country’s national park management agency, and Carbon Tanzania with revenues going to local communities.

Much of the impetus has been given by the World Bank which has been an early supporter of a number of projects across the continent8. One of the first was a vehicle scrapping and recycling project in Egypt which has led to replacing over 40,000 old taxis in Cairo alone and helped avoid the equivalent of 130,000 tons of carbon dioxide within its first year. Not only has the new taxi fleet reduced emissions of a range of airborne pollutants, but it also contributed to increased traffic safety across the country.

Another project has been increasing the reach of the Olkaria II geothermal project in Kenya. The Unit 3 Geothermal Expansion Project has added a third 35 megawatt generator, which adds around 276 gigawatts of electricity to the Kenyan national grid. This has helped the project to issue over 230,000 carbon credits in its first year.

In Nigeria, the Earthcare Solid Waste Composting Project is the first composting activity in the country to be registered with the Clean Development Mechanism, which allows a country with an emission-reduction or emission-limitation commitment under the Kyoto Protocol to implement an emission-reduction project in developing countries9. It has reduced the amount of waste disposed in landfills in Nigeria’s capital by up to 20% and issued around 30,000 carbon credits in its first year of operation.

The Zambian Experience

Zambia is one the latest African countries to update its climate laws and regulations as part of a roadmap to participating in the international carbon markets. In March, the Zambian government drew up a draft law on carbon credits to establish eligibility criteria and approval processes for projects10.

The bill intends to regulate the establishment of a carbon market and trading in Zambia, as well as the creation of a climate change fund11.

The draft law requires project developers to register with the relevant government agencies and obtain a certificate of authorization and includes fines and prison sentences ranging from six months to 10 years for non-compliance. More to the point, the government has made sure that the needs of communities are considered in any disputes that arise from carbon credit projects.

The country’s aim is to balance its natural resources with sustainable growth. The World Bank estimates that Zambia holds 2% of global copper reserves as well as significant quantities of other minerals like cobalt, nickel, and manganese12.

A month later, in early April, the government in Lusaka approved a new financial mechanism to accelerate energy access across the country through mini-grids13. In its first phase, what has been called the Demand Stimulation Incentive is targeting mini-grid deployments across 100 priority sites. This is expected to impact the livelihoods of 30,000 rural Zambians and the welfare of over 100,000 Zambians by electrifying schools, hospitals, and other community institutions.

The Zambian Experience

Zambia is one the latest African countries to update its climate laws and regulations as part of a roadmap to participating in the international carbon markets. In March, the Zambian government drew up a draft law on carbon credits to establish eligibility criteria and approval processes for projects10.

The bill intends to regulate the establishment of a carbon market and trading in Zambia, as well as the creation of a climate change fund11.

The draft law requires project developers to register with the relevant government agencies and obtain a certificate of authorization and includes fines and prison sentences ranging from six months to 10 years for non-compliance. More to the point, the government has made sure that the needs of communities are considered in any disputes that arise from carbon credit projects.

The country’s aim is to balance its natural resources with sustainable growth. The World Bank estimates that Zambia holds 2% of global copper reserves as well as significant quantities of other minerals like cobalt, nickel, and manganese12.

A month later, in early April, the government in Lusaka approved a new financial mechanism to accelerate energy access across the country through mini-grids13. In its first phase, what has been called the Demand Stimulation Incentive is targeting mini-grid deployments across 100 priority sites. This is expected to impact the livelihoods of 30,000 rural Zambians and the welfare of over 100,000 Zambians by electrifying schools, hospitals, and other community institutions.

Overcoming Challenges; Grasping the Opportunity

The carbon markets have largely shaken off last year’s scandals surrounding organizations that certified carbon credits14. The sector’s new credibility and professionalization is likely to benefit Africa.

This is not to say that it will be clear sailing from now on. Institutional and regulatory hurdles remain which could slow down the development and effectiveness of the carbon markets. A robust national carbon market framework is often lacking and, more to the point, the question of whether the purpose of carbon markets is to reduce emissions or is simply a way to raise capital remains unanswered15. The scandals that emerged in 2023 showed that carbon credits were not always used for their intended purposes and were being used by corporations to whitewash their reputations16.

Nonetheless, steps have been taken in the right direction. The continent received a boost at the COP28 Summit in Dubai in November 2023 when the United Arab Emirates (UAE) committed to buying $450mn of carbon credits from the Africa Carbon Markets Initiative (ACMI).The ACMI, set up to support the growth of carbon credit production and create jobs in Africa, wants to produce 300 million carbon credits a year by 2030 and intends to generate $6bn in revenue and 30 million jobs by 203017. The organization was given a further boost after the African Development Bank announced its official membership of the ACMI in May this year. It has said that it will help African countries and the private sector to secure additional resources to combat climate challenges18.

While no countries in Africa have yet implemented emissions trading systems as Brazil, Colombia, Chile, and Mexico have done, the route from there to establishing carbon prices like Europe is becoming an increasingly well-trodden path. The direction of travel and opportunities for Africa are clear.