Collective Action Clauses

for State-Owned Enterprises:

A Logical Next Step?

Few regions have had more experience of sovereign debt crises than Latin America. Since the turn of the 20th Century, Latin America has experienced regular cycles of economic boom and bust, in correlation to similar cycles in the markets for commodities produced by these countries.

Countries in the region have historically borrowed heavily during the boom years and have then been forced to reprofile or restructure the resulting obligations in leaner times. Sovereign borrowing in earlier periods generally involved a limited number of players, such as other sovereigns, multilateral institutions, and banks.

The arrival of sovereigns onto the global capital markets has, however, significantly expanded the universe of creditors to many different types of financial investors, many of which have conflicting interests. As a result, following the most recent rounds of protracted and damaging sovereign debt defaults in which some hedge funds held out for better deals, the use of New York law-based collective action clauses (CACs) in the region’s sovereign debt issuance has become almost universal.

CACs enable sovereigns to take control and speed up debt restructuring processes. Issuers can propose debt plans that only need the backing of a majority or supermajority of creditors. Such clauses can also find support among investors by avoiding the potential for a holdout to derail a debt plan that might be acceptable to the majority, but also find detractors (mainly among investors favouring holdout strategies) who argue that they remove an important piece of leverage that creditors have and can provoke moral hazard by making debt restructuring less painful for sovereigns.

In 2020, both Ecuador and Argentina managed to restructure billions in foreign-governed bonds thanks to CACs. Although the process required long negotiation, Argentina ultimately defused concerns of a disorderly default by receiving over 93% backing for its proposal to restructure $65bn of its debt, allowing the country and its creditors to move on.

Few regions have had more experience of sovereign debt crises than Latin America. Since the turn of the 20th Century, Latin America has experienced regular cycles of economic boom and bust, in correlation to similar cycles in the markets for commodities produced by these countries.

Countries in the region have historically borrowed heavily during the boom years and have then been forced to reprofile or restructure the resulting obligations in leaner times. Sovereign borrowing in earlier periods generally involved a limited number of players, such as other sovereigns, multilateral institutions, and banks.

The arrival of sovereigns onto the global capital markets has, however, significantly expanded the universe of creditors to many different types of financial investors, many of which have conflicting interests. As a result, following the most recent rounds of protracted and damaging sovereign debt defaults in which some hedge funds held out for better deals, the use of New York law-based collective action clauses (CACs) in the region’s sovereign debt issuance has become almost universal.

CACs enable sovereigns to take control and speed up debt restructuring processes. Issuers can propose debt plans that only need the backing of a majority or supermajority of creditors. Such clauses can also find support among investors by avoiding the potential for a holdout to derail a debt plan that might be acceptable to the majority, but also find detractors (mainly among investors favouring holdout strategies) who argue that they remove an important piece of leverage that creditors have and can provoke moral hazard by making debt restructuring less painful for sovereigns.

In 2020, both Ecuador and Argentina managed to restructure billions in foreign-governed bonds thanks to CACs. Although the process required long negotiation, Argentina ultimately defused concerns of a disorderly default by receiving over 93% backing for its proposal to restructure $65bn of its debt, allowing the country and its creditors to move on.

CACs Use Likely to Increase

Having proved their value in the sovereign sphere, CACs are being increasingly discussed for state-owned enterprises that often hold a country’s crown jewel assets. But applying similar rules to large state-backed businesses in oil and gas, utilities, or transport, raises new questions and challenges. For instance, while creditors have little claim over assets in a sovereign restructuring process (owing to sovereign immunity doctrine for non-commercial assets), state-owned enterprises frequently have significant portfolios of assets for commercial use that could be sold to maximise value for creditors.

By inserting CACs into debt agreements for state-backed companies, countries may undermine faith in their corporate restructuring processes, which could impact inflows of international investment capital and domestic companies’ access to the international capital markets. On the other hand, few countries wish to see state-owned enterprises go through turbulent, and in many cases untested, corporate restructuring processes in open court, and therefore might favour broader use of CACs.

Such clauses were recently used to restructure debt for Tocumen International Airport – Panama City’s main airport – and have recently been included in bonds issued by Empresa Nacional del Petróleo (ENAP) – Chile’s state-owned oil company.

There are also part state-owned businesses across the region that have relied on CACs to avoid default and push through debt renegotiations. In February 2020, Argentina’s largest oil group YPF – majority-owned by the state – reached an agreement with enough of its creditors to roll over debt repayments, a move that freed up company capital to boost shale oil and gas production. The move was welcomed by the ad hoc creditor group, comprised of investors including BlackRock1.

We expect the use of CACs to become more commonplace in new state-owned enterprise debt issuance as volatility around energy supply and pricing continues, and the impact of COVID persists in sectors such as the transportation. Governments in Latin America do not want to see their flagship national businesses go through protracted and painful restructuring processes, and least of all be subject to U.S.-style bankruptcy proceedings.

Features of CACs in State-Owned Enterprises

In contrast to the unanimous creditor consent required in SEC-registered corporate bonds governed by New York law (the Trust Indenture Act 1939), CACs enable state-owned enterprise issuers to propose a menu of debt restructuring options that need a lower threshold of creditor approval.

Indeed, CACs are a feature of bonds issued under English law (as far back as the Victorian era), which has resulted in some Latin American state-owned enterprises turning to that regime for issuing new debt. Among them, Brazilian electricity utility Eletrobras has favoured issuing bonds under English law and has used CAC mechanisms to alter the terms of its debt. However, while the use of CACs under English law does give sovereigns greater control, precedent in case law prevents coercive practices that may be too punitive for bondholders.

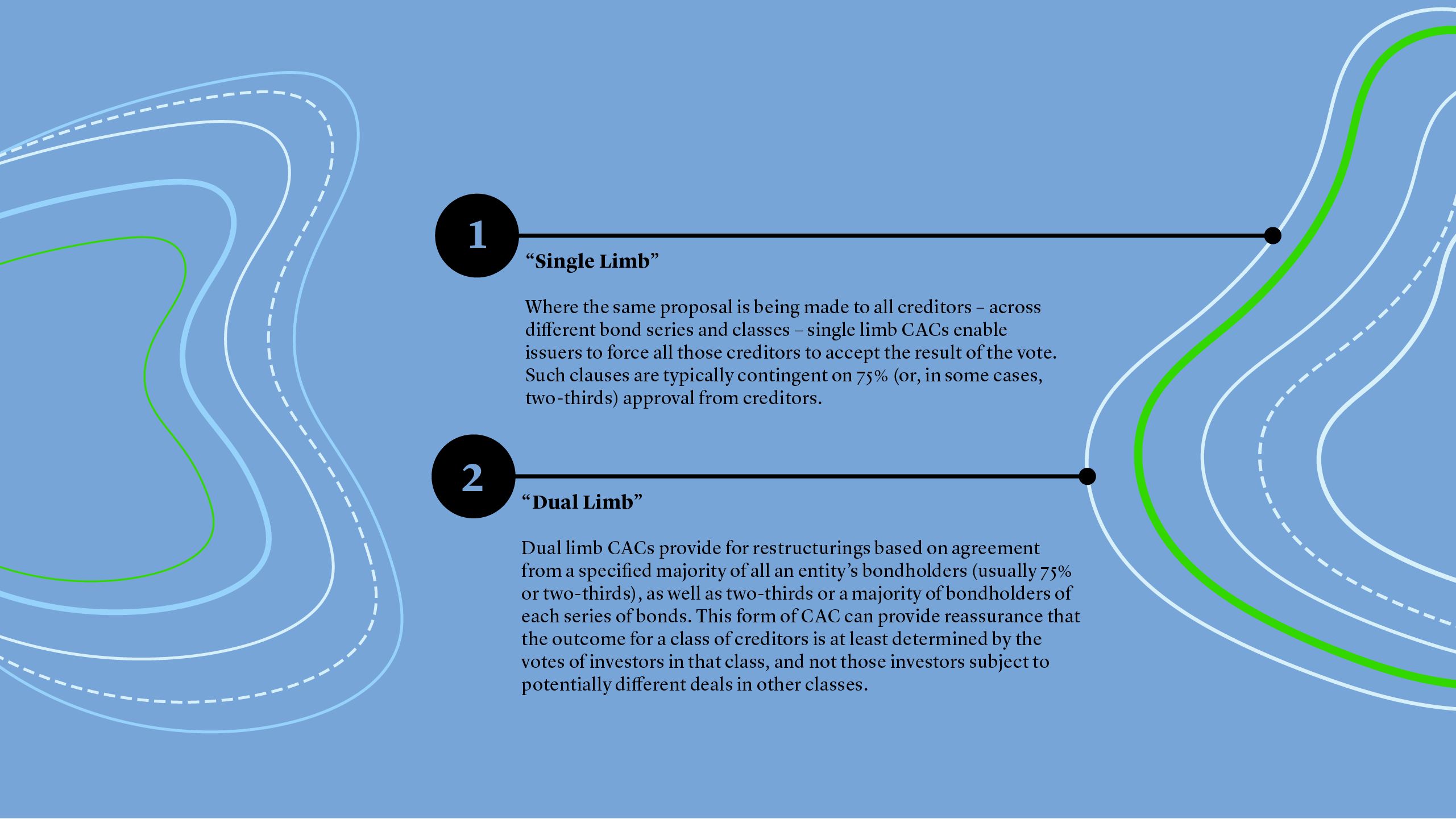

To date, state-owned enterprises have typically echoed the simplest form of sovereign CACs. In other words, altering the amendments clause of a single bond to allow the issuer to change the fundamental terms of that debt on agreement from a majority of creditors. There are two evolutions of sovereign CACs that could be applied to state-owned enterprise debt.

There are other ways in which these CACs may be adapted for state-owned enterprises. That may include changes to the level of bondholder approval, or flexibility around the debt terms being restructured – for example, CACs that allow for debt rescheduling but not outright cancellation or forgiveness. As CACs move into the state-owned enterprise space, we expect more innovation.

Making the Case for CACs in State-Owned Enterprises

There are drawbacks as well as benefits from putting CACs in state-owned enterprise debt issuance. Ultimately, the decision depends on whether the issuer wants the business to look and behave as a commercial entity or a quasi-sovereign in its own right.

Pros

- Bonds are easier to restructure – the process can be done privately with little cost, time and media attention.

- Integration with the sovereign – clauses can be drafted that align and integrate the state-owned enterprise’s debt with that of the sovereign.

- Less reliance on lenders of last resort – as clauses have helped sovereigns bypass the IMF, CACs could help state-owned enterprises avoid the need to turn to the state for support.

- Empowers the majority creditors – CACs put the power in the hands of creditors who favour quick outcomes and want solutions that protect value and minimise downside, as opposed to extracting maximum value.

Cons

- Unpopular with certain investors – CACs reduce creditors’ negotiating power and are particularly unpopular with hedge funds who employ hold out strategies and similar types of investors.

- Are they meaningfully useful? – as quasi-sovereigns, creditors may have little practical recourse to company assets in restructurings (particularly for assets that are considered to be used in the national interest, or mainly located within the borders of the country), effectively reducing the benefits of CACs to state-owned companies.

- Undermine the local investment regime – taking state-owned enterprises out of the domestic restructuring and bankruptcy regime that corporates are subject to may undermine confidence in the system and reduce international investment into private companies, or limit those companies’ access to international capital markets.

Conclusion

Following the growth of CACs in sovereign bonds, the door is opening to their more widespread use in state-owned enterprise debt. Public companies – and the states that back them – will need to consider whether CACs really provide the protections they want and fit with the regimes they hope to promote. Creditors will need to weigh the reduction in their negotiating power against simpler restructuring processes, and consider the benefits of owning debt in state-owned enterprises versus corporate bonds.

You can read more about CACs in Latin American sovereign bonds by reading our piece.