They may be a relatively new concept, but sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are on a significant growth trajectory. The first bond of its kind was issued by Italian utility company Enel in 2019 and was followed by other corporations such as Novartis and Chanel1, as well as Brazilian paper producer, Suzano.

While traditional bonds are slowing down, global sustainable bond issuance is expected to exceed $1.5tn in 2022 and SLBs are the fastest-growing segment within this market2. In March 2022, Chile was the first sovereign to ever issue an SLB. Now, other sovereigns are actively considering this path, including Uruguay, which is pushing for developing countries to obtain funding to fight climate change and “meet more ambitious climate goals,”3 and Ghana, which published a framework that includes the possibility to issue SLBs4.

They may be a relatively new concept, but sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are on a significant growth trajectory. The first bond of its kind was issued by Italian utility company Enel in 2019 and was followed by other corporations such as Novartis and Chanel1, as well as Brazilian paper producer, Suzano.

While traditional bonds are slowing down, global sustainable bond issuance is expected to exceed $1.5tn in 2022 and SLBs are the fastest-growing segment within this market2. In March 2022, Chile was the first sovereign to ever issue an SLB. Now, other sovereigns are actively considering this path, including Uruguay, which is pushing for developing countries to obtain funding to fight climate change and “meet more ambitious climate goals,”3 and Ghana, which published a framework that includes the possibility to issue SLBs4.

What Are Sustainability-Linked Bonds?

Unlike traditional green bonds, which ringfence funds for specific purposes, SLBs – or key performance indicator (KPI)-linked bonds – take a holistic approach to the problem. While funds can be used for any purpose, the bonds’ interest rates are tied to an issuer’s success at meeting specific pre-agreed sustainability targets. This approach tackles concerns over greenwashing by focusing on the big picture. While traditional green bonds fund wind turbines, the same issuer can simultaneously turbocharge its coal production. SLBs, on the other hand, reward issuers for achieving tangible results, such as lowering emissions or reducing deforestation.

Chile’s First-Ever Sovereign Sustainability-Linked Bond

On March 7, 2022, Chile achieved a historic milestone by being the first sovereign to issue an SLB. Notwithstanding the fact that it was issued in the midst of the international crisis involving Ukraine and the resulting volatility and uncertainty of the conflict in the global economy and financial markets, the bond was well received, with demand of $8.1bn, 4.1 times the offered amount5.

The climate change targets contemplated by Chile’s SLB include:

- Complying with two maximum CO2 emission targets in line with Chile’s commitments under the Paris Agreement.

- Reaching 60% of electricity production through non-conventional renewable energies by 2032.

Failure to meet any such target carries financial consequences for Chile, in the form of a coupon ‘Step-Up’.

Sovereign SLBs: Challenges and Potential Innovations

All corporate SLBs issued to date have followed the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles (2020). However, such principles were drafted with corporations in mind, and so the ICMA’s guidelines and recommendations may not be directly applicable to sovereigns. Sovereign SLBs will need their own flexibility, but will also need to ensure fairness and transparency if they want to be palatable to the market.

Structuring SLB Issuances

The first challenge that sovereigns encounter when structuring an SLB is tied to the holistic nature of these bonds. Sovereign bonds are traditionally managed by a country’s ministry of finance or its equivalent. However, as SLBs carry wider policy implications, they require a remarkable amount of cooperation with other ministries, such as the ministry of environment if the KPIs are environment-related or the ministry of foreign affairs if there is a link to a commitment under an international treaty. This cooperation among ministries does not end upon the issuance of the bond but instead will remain, at the very least, until the date in which compliance with the sustainability performance targets is verified.

Pushing forward an intra-ministerial project of this magnitude for a project that will involve many years or even decades requires the deployment of a considerable amount of financial and human resources, as well as patience. Countries that tap the market frequently should consider beginning this process even if they are not currently contemplating a specific SLB.

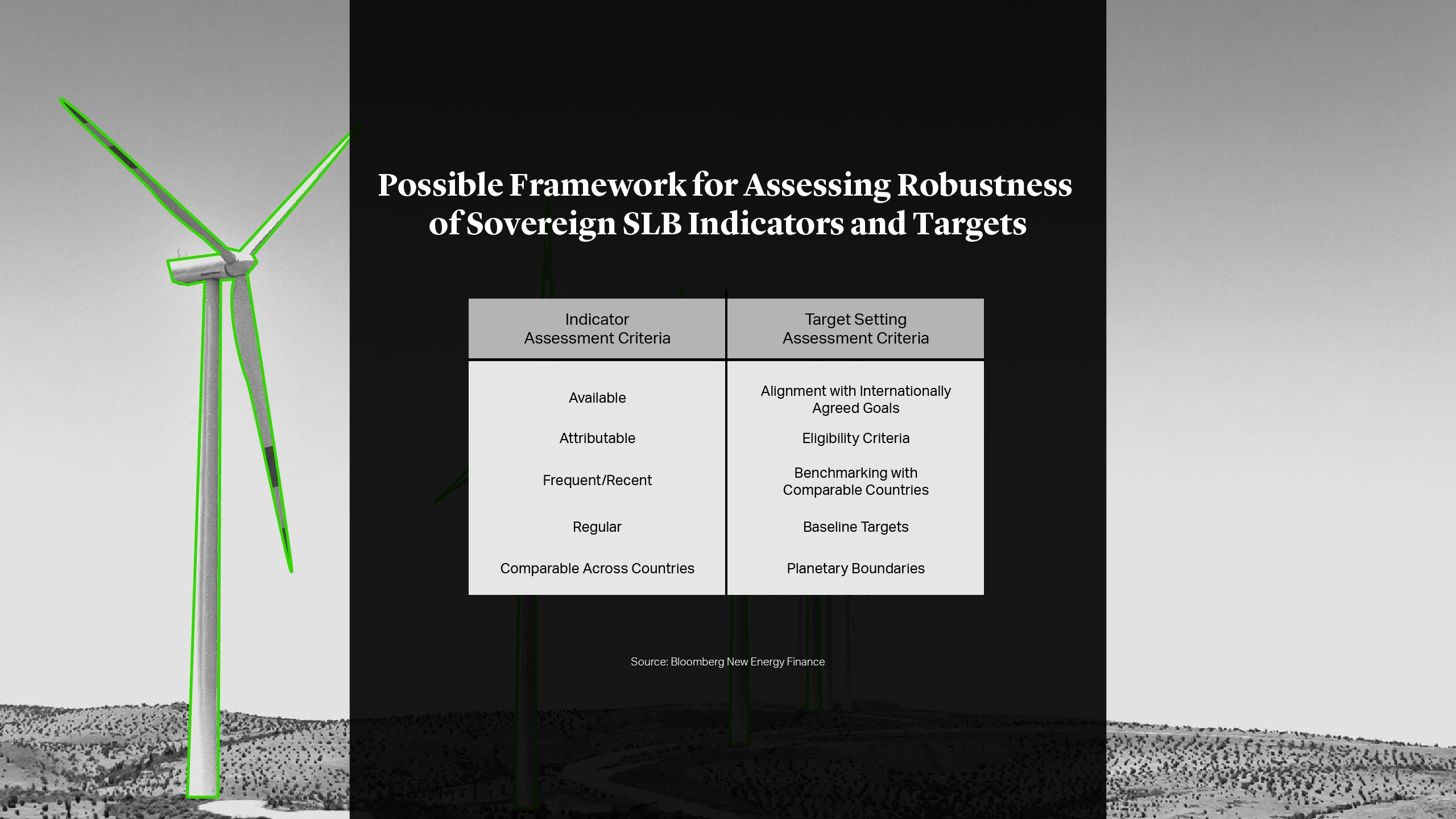

Selecting KPIs

The most common KPIs seen in corporate market SLBs relate to emission reductions, but other targets have included water use and reintroducing endangered species into ecosystems. As sovereigns begin issuing SLBs, a wider pool of KPIs could inject uncertainty into the market. To avoid this, the World Bank recommends sticking to a limited number of globally recognised KPIs and it is currently working on a framework for evaluating them6. Our view is that the selected KPIs should be relevant to a sovereign’s social and environmental issues and fit into its sustainable development goals and narrative.

We anticipate that most sovereigns will tend to select KPIs tied to existing objectives which they have been measuring or reporting on prior to considering the SLB. This could include Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) within the framework of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, which is one of the targets selected by Chile.

With over 200 sovereigns signed up to the Paris Agreement, its firm international recognition offers greater certainty and sovereigns are already reporting on their performances against its key terms. The United Nations is also reportedly working on a compliance framework for the Paris Agreement, which would provide further certainty when measuring performance against KPIs connected to it.

Sustainability Performance Targets

KPIs for sovereign issued SLBs should be tied to one or more Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs). Selected SPTs should be reasonably achievable, but also sufficiently ambitious to attract investors. However, selecting ambitious SPTs might prove hard in scenarios where the KPI is tied to a pre-existing target which the sovereign is close to meeting. This could be the case with any targets tied to a country’s commitments under its NDCs, if the SLB is to be issued only a few years prior to the date when the Paris Agreement target will be verified.

The ICMA also encourages selecting SPTs that allow for benchmarking against peers. However, consideration should be given that each country’s geographic and environmental setting, as well as its political, social and economic context, is unique. Depending on the KPI, comparison among peers may therefore not be adequate or fair.

Reporting on KPIs

In accordance with the ICMA’s Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles (SLBP), reports should be published regularly, at least annually7. This is in contrast to most sovereign’s reporting cycles under their NDC commitments, which generally span a period of over two years.

The frequency of the reports is not the only area where reporting under the framework of the Paris Agreement diverges from markets’ demands with regard to SLBs either. There is also a delay between the observation date and the reporting date. Despite this, in the case of Chile’s SLBs, the market seems to have been comfortable with the reporting of the KPI tied to CO2 emissions every two years, consistent with requirements under the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC). It remains to be seen if investors will push for shorter reporting periods as the offer of sovereign SLBs increases.

In addition, sovereigns will face an additional challenge if the selected KPI is something they do not currently report on. The logistics of reporting on KPI performance should be considered in advance as, aside from the logistical issues, a new KPI could require sovereigns to disclose more data than they would like, attracting public scrutiny which may be unwelcome.

Verification and Audit

The ICMA’s Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles require an issuer’s performance against KPIs to be determined by an independent professional, such as an auditor or environmental expert. Sovereigns operate differently though, and another layer of uncertainty lies in how future KPIs will be assessed. Under the UNFCCC, member parties’ reports are subject to the International Consultation and Analysis (ICA) process, which conducts its technical review during a two-year period. If a sovereign wants to provide investors with verification reports on a shorter timetable, they might have to find a way around the ICA process through a third party.

However, having a party other than these experts operating under the ICA process review and reporting on the KPIs could potentially lead to different results in the context of the SLB and Paris Agreement.

Bond Characteristics

The characteristics of sovereign SLBs are unlikely to differ significantly from that of corporations, but there is room for differences and innovations.

Coupon “Step-Downs”

Chile’s SLB, as well as most corporate SLB issuances, is structured with a “Step-Up” coupon, which requires issuers to pay higher interest rates should they fail to hit targets. According to the World Bank, sovereign SLBs are likely to use a “Step-Down” structure, which would reward countries for pursuing ambitious targets. This offers a positive incentive for countries to aim higher, but there are no guarantees that investors will happily pay this premium.

Force Majeure

As the past few years have shown, even seemingly achievable targets can be derailed by unforeseen circumstances. Corporate SLBs have generally allowed issuers to exclude factors outside their control. Sovereign issuers may want to do the same, considering carefully which unforeseen events they should exclude when drawing up bond documents.

However, if the selected KPI is tied to a sovereign’s NDCs or other pre-existing targets which do not account for acts of God, it might be preferable not to include provisions in the SLB documentation that could lead to the sovereign reporting it has met the SLB targets, but not those tied to its NDCs, even if they are presumably the same.

Most Favoured Nation

In its SLB, Chile innovated by incorporating a “most favoured nation” clause, which has no precedent in the corporate world. In accordance with this clause, the terms and conditions of these bonds will be adjusted to include more ambitious sustainability performance targets included in a future SLB issuance by Chile that is based on the same KPI and same event observation dates. Investors might want other sovereigns (and corporations) to follow the same path.

Conclusion

SLBs hold significant promise for sovereigns. They could fund immediate COVID-19 relief for hard-hit nations, while simultaneously paving the way for longer-term sustainable development. However, alongside the significant opportunities they offer, come unique challenges that sovereigns will need to recognise and plan for.

Juan G. Giráldez

Partner

São Paulo

T: +55 11 2196 7202

jgiraldez@cgsh.com

V-Card

Ignacio Lagos

Associate

New York

T: +1 212 225 2852

ilagos@cgsh.com

V-Card

Lara Gomez Tomei

Associate