As Carney, Lagarde and many others have pointed out, we have already seen a collapse in values for those such as coal companies that were hard hit by the move to decarbonisation. As those efforts continue and countries strive to meet Paris climate targets, assets that are prized today could become worthless tomorrow. This poses a question for every company, and perhaps particularly financial institutions such as banks and insurers – as Carney put it, “What is your plan1?”

Carney is not the only one asking. The last couple of years have seen a renewed focus on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues for financial sector firms. Regulators across the world have begun demanding answers from credit institutions about their exposures to ESG risks, including after the COVID-19 pandemic emphasised banks’ crucial role for society in supporting businesses and individuals through crisis.

Europe took a head start in ESG regulatory efforts, with the Commission’s 2018 Action Plan on Sustainable Finance. Since Brexit, the United Kingdom has declared its intention to match the EU’s ESG ambitions. Several Asian countries have followed suit. And with the recent change in administration in the United States - where ESG pressure on financial institutions was until now mostly propelled by private investors - even regulators in Washington are beginning to consider how to regulate the sustainable finance space.

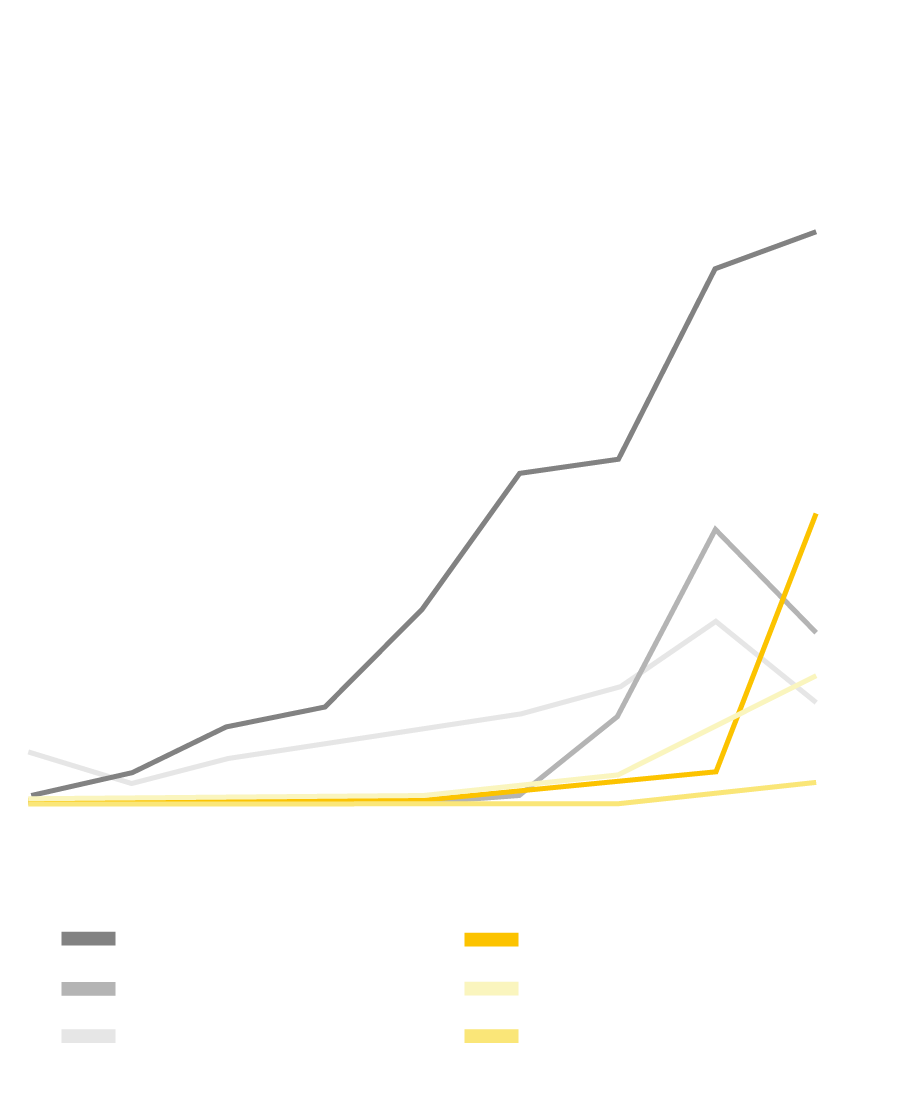

Investors, too, are having a role to play in the transition. Growth of ESG funds in recent years has been phenomenal. Assuming a 15% increase (half the pace registered over the past 5 years), ESG assets are on track to exceed 1/3 of all global assets under management (or over $53 trillion2) by 2025. Europe alone already accounts for half of the current $40 trillion in ESG.

Asset managers are following suit and making their presence felt, pushing the businesses they invest in to become more sustainable3. More than 500 institutional investors together accounting for over $50 trillion of assets worldwide have committed to supporting the “Climate Action 100+” initiative, aimed at ensuring that the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters act on climate change. As the world’s largest asset manager, Blackrock4 has famously committed to putting sustainability at the core of its investment strategy and went so far as to place several of its portfolio companies publicly “on watch” for their insufficient progress on climate issues5.

And it’s not just equities: governments and companies are expected to issue $500 billion in green debt globally in 20216. In the EU, ESG bond issuance reached a record €55.2 billion in Q2 2020 alone7, with the Commission having committed to raising at least one third of its €750 billion recovery package in green debt – raising hopes that Europe could lead an ESG recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. The numbers cannot surprise, also given that green bonds today deliver a tangibly cheaper cost of capital compared to vanilla bonds (in what’s been dubbed a “greenium”), again reflecting scarcity and investor demand.

Few banks can afford to ignore such trends in investor appetites.

Investors, too, are having a role to play in the transition. Growth of ESG funds in recent years has been phenomenal. Assuming a 15% increase (half the pace registered over the past 5 years), ESG assets are on track to exceed 1/3 of all global assets under management (or over $53 trillion2) by 2025. Europe alone already accounts for half of the current $40 trillion in ESG.

Asset managers are following suit and making their presence felt, pushing the businesses they invest in to become more sustainable3. More than 500 institutional investors together accounting for over $50 trillion of assets worldwide have committed to supporting the “Climate Action 100+” initiative, aimed at ensuring that the world’s largest corporate greenhouse gas emitters act on climate change. As the world’s largest asset manager, Blackrock4 has famously committed to putting sustainability at the core of its investment strategy and went so far as to place several of its portfolio companies publicly “on watch” for their insufficient progress on climate issues5.

And it’s not just equities: governments and companies are expected to issue $500 billion in green debt globally in 20216. In the EU, ESG bond issuance reached a record €55.2 billion in Q2 2020 alone7, with the Commission having committed to raising at least one third of its €750 billion recovery package in green debt – raising hopes that Europe could lead an ESG recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. The numbers cannot surprise, also given that green bonds today deliver a tangibly cheaper cost of capital compared to vanilla bonds (in what’s been dubbed a “greenium”), again reflecting scarcity and investor demand.

Few banks can afford to ignore such trends in investor appetites.

Despite the demand-driven push, in the words once again of Christine Lagarde: “Climate change-related risks have the potential to become systemic for the Euro area, in particular since there are indications that markets are not pricing the risks fully”. Policy makers are aware that a sudden reassessment of climate exposures by markets could have significant negative impacts on the financial system, including banks.

The attention is not surprising given regulators’ continued focus on systemic risk since the financial crisis of 2007-2008. Climate change can certainly produce considerable and widespread financial (i.e, credit, operational and market-related) risk. In February 2020, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision established a “Task Force on Climate-related Financial Risks” (TFCR), which is looking at the extent to which climate-related financial risks are incorporated in the existing framework and the supervisory practices that might be most effective to mitigate them. The work of the TFCR began with a stocktake of members’ existing initiatives, and found that, as a minimum, all respondents were aware of the financial stability implications of climate change8. In April 2021, the TFCR published two reports on the transmission channels between climate physical and transition risks hand and traditional financial risk categories (i.e, credit, market, liquidity and operational risk), and on the type of data and measurement methodologies that will be necessary for estimating climate-related financial risks9. The Basel Committee will build on these reports to propose supervisory practices integrating climate related financial risks into prudential banking regulation.

In Europe and the UK in particular, these priorities have made it to the top of regulators’ agenda and are likely to soon produce profound adjustments in the regulation and supervision of banks.

Despite the demand-driven push, in the words once again of Christine Lagarde: “Climate change-related risks have the potential to become systemic for the Euro area, in particular since there are indications that markets are not pricing the risks fully”. Policy makers are aware that a sudden reassessment of climate exposures by markets could have significant negative impacts on the financial system, including banks.

Climate change-related risks have the potential to become systemic for the Euro area, in particular since there are indications that markets are not pricing the risks fully.

The attention is not surprising given regulators’ continued focus on systemic risk since the financial crisis of 2007-2008. Climate change can certainly produce considerable and widespread financial (i.e, credit, operational and market-related) risk. In February 2020, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision established a “Task Force on Climate-related Financial Risks” (TFCR), which is looking at the extent to which climate-related financial risks are incorporated in the existing framework and the supervisory practices that might be most effective to mitigate them. The work of the TFCR began with a stocktake of members’ existing initiatives, and found that, as a minimum, all respondents were aware of the financial stability implications of climate change8. In April 2021, the TFCR published two reports on the transmission channels between climate physical and transition risks hand and traditional financial risk categories (i.e, credit, market, liquidity and operational risk), and on the type of data and measurement methodologies that will be necessary for estimating climate-related financial risks9. The Basel Committee will build on these reports to propose supervisory practices integrating climate related financial risks into prudential banking regulation.

In Europe and the UK in particular, these priorities have made it to the top of regulators’ agenda and are likely to soon produce profound adjustments in the regulation and supervision of banks.

A Prudential Look at Climate Risks in the European Union and the United Kingdom

Four key categories of risk…

Broadly, threats to financial stability that are posed by climate change can be categorised under four distinct types of risks:

Physical risks

Physical risks are those that arise from climate change itself, such as the consequences brought by increasingly frequent severe weather events. In the words of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, physical risk “arises from the material, operational, or programmatic impairment of economic activity, and the corresponding impact on asset performance from the shocks and stresses attributable to climate change.”10

Transition Risks

Transition risks are instead costs that arise from the responses to climate change in society, markets, policies and regulation – what the European Central Bank (ECB) defines as “financial loss that can result, directly or indirectly, from the process of adjustment towards a lower-carbon and more environmentally sustainable economy”11. The (mis)fortunes of U.S. coal companies are a prime example of this.

Liability Risks

Liability risks come from people or businesses seeking compensation for losses suffered as a result of physical or transition risks. As young climate activist, Greta Thunberg has forewarned: “If you choose to fail us, we [i.e, younger and future generations] will never forgive you”.

Compliance Risks

Compliance risks will also likely accompany transition risks as regulations evolve. New regulations may be uncertain in scope or application and conflict with existing regulatory requirements.

Regulatory levers are a primary tool for governments to orient investment in support of climate transition goals. Those who fail to adapt and respond to its nudges will face rising costs. Those that can plan ahead of the changes will undoubtedly grasp multiple opportunities.

…And Three Pillars

With the Basel Committee’s own recognition of the potential for climate risk to manifest itself as financial risk, comes the possibility of integrating environmental policy directly into the Basel framework.

In the EU, the revised Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR II) and Capital Requirements Directive (CRD V) envisage addressing climate-related risks across each of the three Basel pillars.

Climate risks are not directly comparable to the systemic risks revealed during the last financial crisis for two essential reasons:

- As will be explored further below, policy-makers’ interest today is not merely focussed on limiting the financial exposure of credit institutions – quite the contrary.

- Relatedly, consensus around appropriate Pillar 1 requirements regarding climate risks does not exist in the way it does for traditional financial risks – and may never do.

Pillar 1: Minimum capital requirements

Within the EU, Article 501c of CRR II12 provides a mandate for the European Banking Authority (EBA) to assess whether to apply a dedicated prudential treatment of exposures related to environmental or social objectives.

The EBA’s report to EU legislators and the Commission is due in June 2025 and will look at:

- Methodologies for assessing the effective riskiness of these exposures compared to the riskiness of other exposures;

- Criteria for evaluating physical risks and transition risks, including the risks related to the depreciation of assets due to regulatory changes; and

- The potential effects of a dedicated prudential treatment of the exposures on financial stability and bank lending.

In practice, the above might mean a rule that favours green investments and loans. A “green-supporting factor”13 would require holding less capital against exposures that contribute to e.g. the low carbon transition (as analogous provisions under CRR 2 already do in some instances for SMEs and infrastructure supporting factors). Conversely, a “brown-penalising factor” could increase capital requirements for assets and loans to sectors with heavy exposure to climate-related risks.

Not everyone is convinced of the merits of either approach. There remains in fact little empirical evidence that green assets are less risky. On the other hand, there could be loopholes that could be exploited to avoid higher capital charges from a brown-penalising factor. The debate is a function of the dual imperatives of climate risk policy: the need to at once “green finance” and “finance green”.

Pillar 2: Supervisory review

Article 98 of CRD V charges the EBA with considering the inclusion of ESG risks in banks’ supervisory review and evaluation process14.

This will include having to develop:

- A uniform definition of ESG risks

- Qualitative and quantitative criteria for assessing their impact on financial stability – including stress testing processes

- Arrangements, processes and strategies for institutions to identify, assess and manage such risks

- Analytical methods and tools to determine the impact of ESG risks on lending

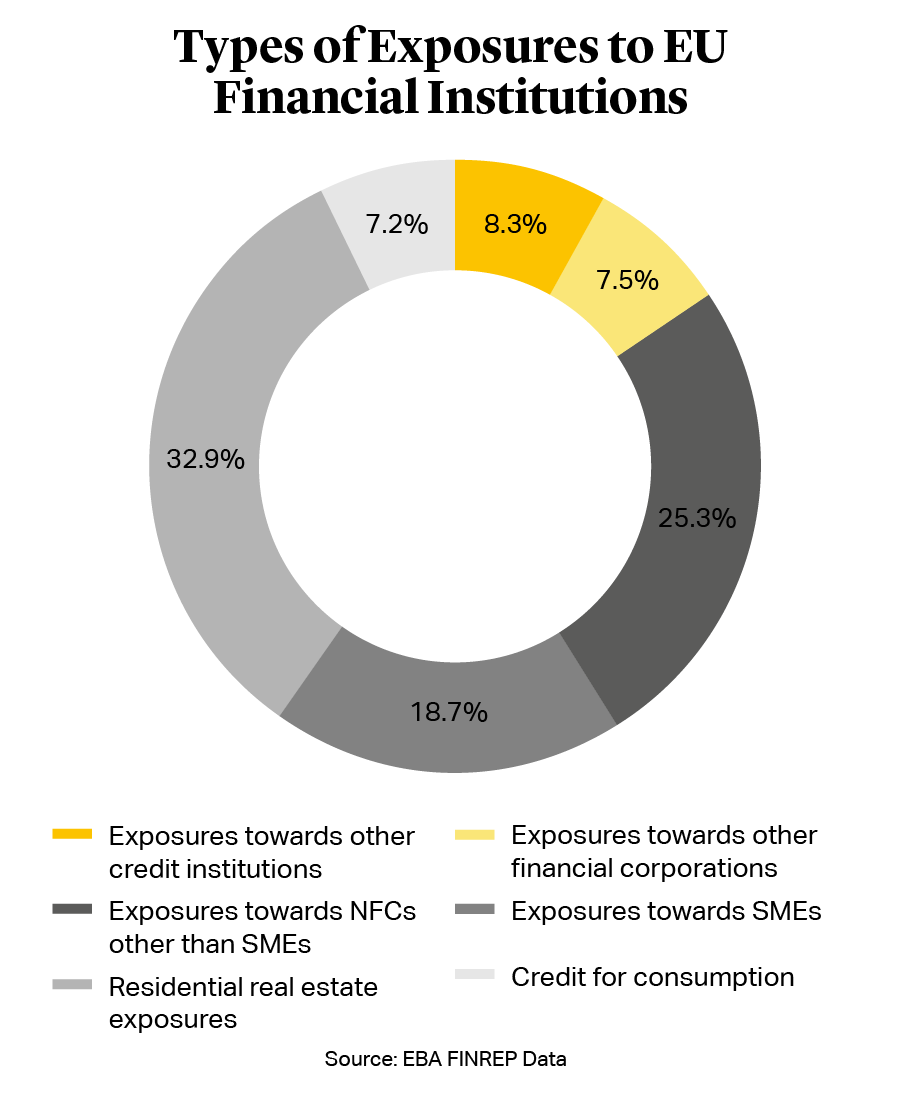

Banks’ feedback to a November 2020 EBA consultation in response to this mandate highlighted the lack of reliable data as a major challenge and the need to develop specific indicators to assess ESG risks. Following up on this mandate, in May 2021 the EBA published a report on its first pilot exercise on mapping climate risk, according to which more than half of banks’ exposures (and 58% of total non-SME corporate exposures to EU obligors) are allocated to sectors that might be sensitive to climate transition risk15.The pilot was designed as a learning exercise to investigate how existing and newly developed climate risk assessment and classification tools perform, and to test banks’ readiness to deal with the related data and methodological challenges.

Overall, the drive to ensure sound management of climate-related risks is likely to bring a host of new supervisory expectations, which central banks and regulators have already begun to outline.

Pillar 3: Disclosure Requirements

Under Article 449a of CRR II, starting in June 2022 large listed institutions will be required to disclose information on ESG risks (both physical and transition)16.

In September 2020, the EBA launched a survey17 to collect information on institutions’ current practices regarding the disclosure of ESG risks and in March 2021, it initiated a public consultation on the draft implementing standards that will specify the new CRR II disclosure requirements18.

The EBA is proposing a sequential approach for the implementation of the CRR II ESG disclosure requirements, encompassing:

- KPIs and quantitative disclosures on climate change transition and physical risks, to show how climate change may exacerbate other risks within the banks’ balance sheets

- Quantitative information on mitigating actions to address climate risks, such as reducing financing activities that reduce the environmental footprint of carbon intensive activities

- Qualitative disclosures for ESG risks targeting governance, business model and strategy and risk management

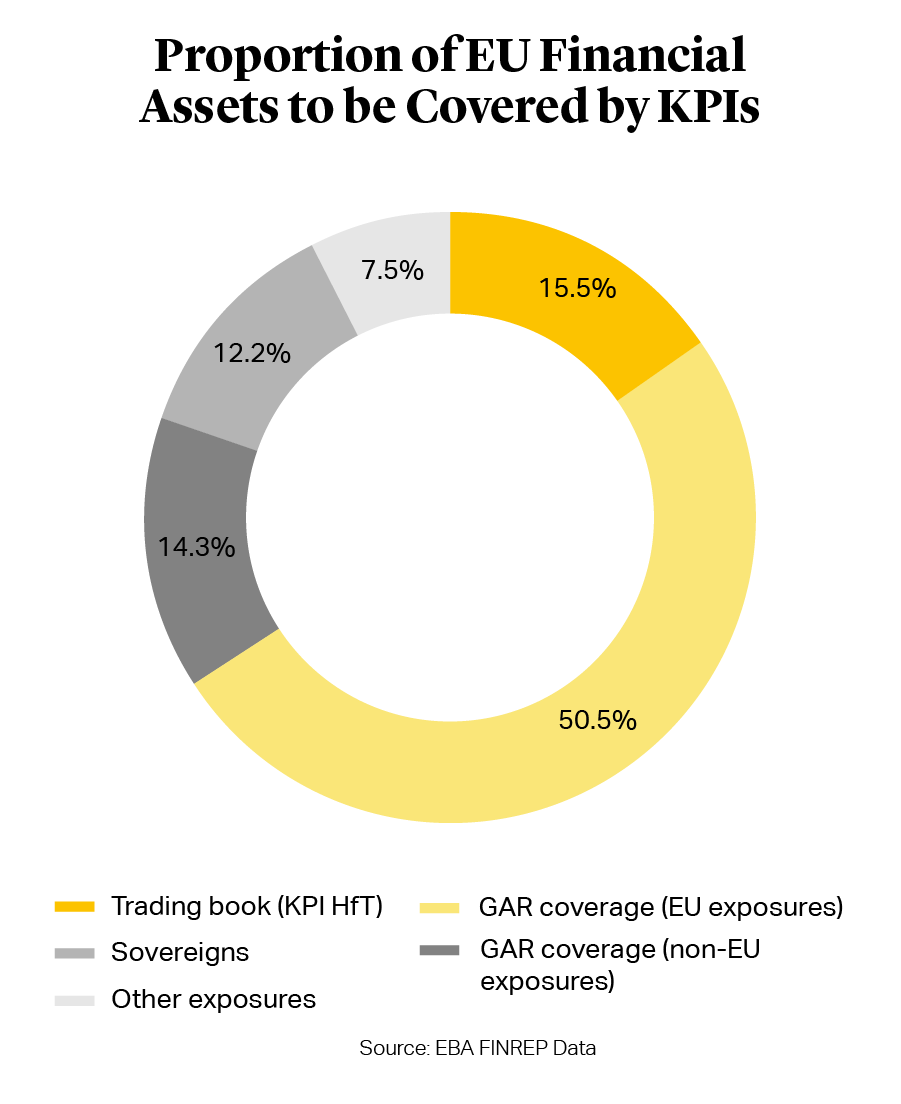

- A “Green Asset Ratio” (GAR) on EU Taxonomy-aligned activities, showing the proportion of assets that contribute substantially to climate change mitigation and adaptation compared to the total assets of held by a bank.

According to the EBA’s proposal19, the GAR would cover a number of exposures to banks’ counterparties within the EU and give information on the sustainability of over 50% of EU banks’ assets. The GAR would be complemented by other KPIs, including a similar ratio for non-EU subsidiaries’ banking business and a KPI covering banks’ trading books. The methodology proposed by the EBA to calculate the GAR has raised controversy in the banking industry, particularly around the lack of data in particular with respect to SMEs and non-EU exposures.

In May 2021, the EBA’s GAR – to be separately calculated on banks’ balance sheet exposures, but also on their investment turnover and capex – was also included as part of the Commission’s new draft delegated regulation issued under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive, which covers large listed (and from 2023 all listed, and large non-listed) banks20.

Overall, new ESG disclosures regimes are likely to accelerate potential regulatory changes under the other two Basel Pillars, by highlighting which banks have more exposure to climate-related risks.

Pillar 1: Minimum capital requirements

Within the EU, Article 501c of CRR II12 provides a mandate for the European Banking Authority (EBA) to assess whether to apply a dedicated prudential treatment of exposures related to environmental or social objectives.

The EBA’s report to EU legislators and the Commission is due in June 2025 and will look at:

- Methodologies for assessing the effective riskiness of these exposures compared to the riskiness of other exposures;

- Criteria for evaluating physical risks and transition risks, including the risks related to the depreciation of assets due to regulatory changes; and

- The potential effects of a dedicated prudential treatment of the exposures on financial stability and bank lending.

In practice, the above might mean a rule that favours green investments and loans. A “green-supporting factor”13 would require holding less capital against exposures that contribute to e.g. the low carbon transition (as analogous provisions under CRR 2 already do in some instances for SMEs and infrastructure supporting factors). Conversely, a “brown-penalising factor” could increase capital requirements for assets and loans to sectors with heavy exposure to climate-related risks.

Not everyone is convinced of the merits of either approach. There remains in fact little empirical evidence that green assets are less risky. On the other hand, there could be loopholes that could be exploited to avoid higher capital charges from a brown-penalising factor. The debate is a function of the dual imperatives of climate risk policy: the need to at once “green finance” and “finance green”.

Pillar 2: Supervisory review

Article 98 of CRD V charges the EBA with considering the inclusion of ESG risks in banks’ supervisory review and evaluation process14.

This will include having to develop:

- A uniform definition of ESG risks

- Qualitative and quantitative criteria for assessing their impact on financial stability – including stress testing processes

- Arrangements, processes and strategies for institutions to identify, assess and manage such risks

- Analytical methods and tools to determine the impact of ESG risks on lending

Banks’ feedback to a November 2020 EBA consultation in response to this mandate highlighted the lack of reliable data as a major challenge and the need to develop specific indicators to assess ESG risks. Following up on this mandate, in May 2021 the EBA published a report on its first pilot exercise on mapping climate risk, according to which more than half of banks’ exposures (and 58% of total non-SME corporate exposures to EU obligors) are allocated to sectors that might be sensitive to climate transition risk15.The pilot was designed as a learning exercise to investigate how existing and newly developed climate risk assessment and classification tools perform, and to test banks’ readiness to deal with the related data and methodological challenges.

Overall, the drive to ensure sound management of climate-related risks is likely to bring a host of new supervisory expectations, which central banks and regulators have already begun to outline.

Pillar 3: Disclosure Requirements

Under Article 449a of CRR II, starting in June 2022 large listed institutions will be required to disclose information on ESG risks (both physical and transition)16.

In September 2020, the EBA launched a survey17 to collect information on institutions’ current practices regarding the disclosure of ESG risks and in March 2021, it initiated a public consultation on the draft implementing standards that will specify the new CRR II disclosure requirements18.

The EBA is proposing a sequential approach for the implementation of the CRR II ESG disclosure requirements, encompassing:

- KPIs and quantitative disclosures on climate change transition and physical risks, to show how climate change may exacerbate other risks within the banks’ balance sheets

- Quantitative information on mitigating actions to address climate risks, such as reducing financing activities that reduce the environmental footprint of carbon intensive activities

- Qualitative disclosures for ESG risks targeting governance, business model and strategy and risk management

- A “Green Asset Ratio” (GAR) on EU Taxonomy-aligned activities, showing the proportion of assets that contribute substantially to climate change mitigation and adaptation compared to the total assets of held by a bank.

According to the EBA’s proposal19, the GAR would cover a number of exposures to banks’ counterparties within the EU and give information on the sustainability of over 50% of EU banks’ assets. The GAR would be complemented by other KPIs, including a similar ratio for non-EU subsidiaries’ banking business and a KPI covering banks’ trading books. The methodology proposed by the EBA to calculate the GAR has raised controversy in the banking industry, particularly around the lack of data in particular with respect to SMEs and non-EU exposures.

In May 2021, the EBA’s GAR – to be separately calculated on banks’ balance sheet exposures, but also on their investment turnover and capex – was also included as part of the Commission’s new draft delegated regulation issued under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive, which covers large listed (and from 2023 all listed, and large non-listed) banks20.

Overall, new ESG disclosures regimes are likely to accelerate potential regulatory changes under the other two Basel Pillars, by highlighting which banks have more exposure to climate-related risks.

As legislators work to update the EU and UK regulatory models, supervisors have already started to provide guidance to banks as to their supervisory expectations vis-à-vis their management of climate related risks.

Guidance of the European Central Bank

The ECB’s November 2020 Guide on Climate-related and Environmental Risks21 showed the way in which EU supervisors expect institutions to:

- integrate climate-related risks when determining and implementing their business strategy, objectives and risk management framework and exercise oversight of them

- explicitly include climate-related and environmental risks in their risk appetite framework

- assign responsibility for the management of climate-related and environmental risks within the organisational structure

- identify and quantify these risks within their overall process of ensuring capital adequacy

- consider them in their credit risk management

- consider their impact on business continuity and in terms of reputational and or liability risks

- monitor the effect of climate-related and environmental factors on their current market risk positions and future investments and develop internal stress tests that incorporate such risk factors

The ECB’s supervisory expectations cover all aspects of EU banks’ business – strategy, risk appetite, governance, and internal reporting – and the whole range of climate derived risks – credit, operational and market risk, as well as liquidity and stress testing.

The institutions that are directly supervised by the ECB under the Single Supervisory Mechanism are expected to consider these risks with immediate effect, whereas those overseen by national competent authorities should apply them “proportionately to their risk profile and business model”.

Guidance by the Bank of England

The ECB is not alone in aligning its supervisory efforts to the new challenges. In the UK, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA)’s April 2019 supervisory statement on “Enhancing banks’ and insurers’ approaches to managing the financial risks from climate change”22 puts out similar expectations, to which UK firms are expected to align by the end of 2021. The PRA will review banks’ disclosures after this deadline and determine whether additional measures are required. Disclosure requirements based on the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) are expected to become mandatory across the whole UK economy by 2025.

The ECB’s and the PRA’s position still seem to differ in one fundamental respect: while the PRA’s angle for now is to tackle climate risks exclusively under Pillar 2 (including by expecting firms to integrate climate risk in their internal capital adequacy assessment process) and Pillar 3, the ECB has signalled the possibility of using the results of its climate stress test to adjust banks’ Pillar 1 capital requirements.

A Mew Model of Risk

While individual supervision and guidance address banks’ micro-level risk-management, at a macro level, climate stress tests are beginning to affirm themselves as supervisors’ preferred tool.

Climate stress tests will generally use the same approach as classic stress tests, in the sense that they will assess the impact of certain scenarios on financial risk metrics, asset value and returns. However, compared to traditional stress tests:

- The horizon of risk materialisation may be much longer – potentially requiring even multi-decade analyses

- Climate stress tests will cover a new set of risks, including (timely, or untimely) changes in climate policy, energy prices and the development of new energy-related technologies

- The effects of these risks will be assessed at the sectoral as well as an infra-sectoral level, as each scenario will have a potentially differentiated impact on firms depending (for instance) on whether or not the counterparties considered employ carbon-intensive business models

Stress Testing Across the UK and EU

At the EU level, the ECB decided to run in 2021 an economy-wide climate stress test which covered approximately 4 million companies worldwide and 2,000 banks23 - almost all monetary financial institutions in the Euro area, 30 years into the future. This comprehensive exercise – conducted centrally by ECB staff in exclusive reliance on the Bank’s internal datasets and models – sought to do the following:

- Assess the exposure of EU banks to future climate risks by analysing the resilience of their counterparties under various climate scenarios

- Inform the climate stress test announced for 2022, which will instead rely on banks’ self-assessment of their exposure to climate change risk and their readiness to address it24.

Some EU Member States – such as The Netherlands25 in 2018 and France26 in 2020 – have already experimented with local climate stress testing pilot exercises in the recent past.

In the UK, the PRA has chosen to dedicate its customary Biennial Exploratory Scenario (BES)27 for 2021 to testing the UK financial system’s resilience to the physical and transition risks associated with different hypothetical climate scenarios, such as a timely vs. a delayed policy action to reach environmental targets set by the 2015 Paris Agreement, plus a “no additional policy action” scenario where the targets are not met and more severe physical risks crystallise as a result. The “Climate BES” (or CBES) will apply a 30-year modelling horizon. To make these extended scenarios credible and tractable, the CBES will examine firms’ resilience using fixed balance sheets, focusing on sizing the risks and the scale of business model adjustment required to respond to these risks, rather than testing the adequacy of firms’ capital to absorb those risks.

Although senior executives of the ECB have stated that the Bank could increase the capital demanded of banks found to be most at risk as early as this year28, we may be some distance away from this happening.

It is, however, evident that regulators are rapidly developing their respective approaches to the supervision of climate risks.

Although banks will need to allow some time before regulators concede total clarity on the future integration of environmental aspects in their prudential regulation and supervision, no one wants to wait for that to come.

These processes will overall ensure with sufficient time that future firm processes build on, rather than reinvent, their own existing risk management devices.

The risks are real. The financial risks that regulators are identifying reflect real-world physical and transition costs. In the words of James Gorman, CEO of Morgan Stanley: “If we don’t have a planet, we’re not going to have a very good financial system.”29

The opportunities to engage early with climate risk are not just about mitigating the impact of regulation, however. The transition to a green economy and a greener financial market presents considerable opportunities for banks. Institutions that can spot and grow their lending activities in promising sectors – which might eventually attract green supporting factors in prudential risk weighting – will certainly benefit in the future. Those failing to adapt will suffer in comparison.

“Transformation Opportunity” - active choices to invest in innovative resilient, zero carbon solutions – is now at the forefront of product developers’ minds in the UK30, who have emphasised the need for a capital allocation framework alongside a risk framework31. It is happening in the EU too: In January 2021, a group of banks released a set of recommendations to regulators in order to help them meet the market’s growing demand for sustainable finance products32. These included providing valid comparability mechanisms for applying the EU Taxonomy to products and firms outside of the EU, and to address the timing mismatch between corporate data availability and the disclosure requirements applicable to banks.

As with much of public perception of the banking sector, prudential regulation remains shaped by the financial crisis more than a decade ago. As Europe and the world move to greener economies, however, a new regime is beginning to take shape to help support investment and lending to sectors that can aid with this transition. There are opportunities for banks to grow their businesses in this environment, and to confirm their role as the global economy’s life conduit and its dynamic, adaptable essential infrastructure.

Mark Carney, former head of the Bank of England and UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance, 201933

Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB, 202134

The risks are real. The financial risks that regulators are identifying reflect real-world physical and transition costs. In the words of James Gorman, CEO of Morgan Stanley: “If we don’t have a planet, we’re not going to have a very good financial system.”29

The opportunities to engage early with climate risk are not just about mitigating the impact of regulation, however. The transition to a green economy and a greener financial market presents considerable opportunities for banks. Institutions that can spot and grow their lending activities in promising sectors – which might eventually attract green supporting factors in prudential risk weighting – will certainly benefit in the future. Those failing to adapt will suffer in comparison.

“Transformation Opportunity” - active choices to invest in innovative resilient, zero carbon solutions – is now at the forefront of product developers’ minds in the UK30, who have emphasised the need for a capital allocation framework alongside a risk framework31. It is happening in the EU too: In January 2021, a group of banks released a set of recommendations to regulators in order to help them meet the market’s growing demand for sustainable finance products32. These included providing valid comparability mechanisms for applying the EU Taxonomy to products and firms outside of the EU, and to address the timing mismatch between corporate data availability and the disclosure requirements applicable to banks.

As with much of public perception of the banking sector, prudential regulation remains shaped by the financial crisis more than a decade ago. As Europe and the world move to greener economies, however, a new regime is beginning to take shape to help support investment and lending to sectors that can aid with this transition. There are opportunities for banks to grow their businesses in this environment, and to confirm their role as the global economy’s life conduit and its dynamic, adaptable essential infrastructure.

Mark Carney, former head of the Bank of England and UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance, 201933

Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB, 202134

European Financial Regulations Outlook 2021

Thursday, June 24 – Thursday, July 22

5:00 p.m. BST | 6:00 p.m. CET

Amélie Champsaur

Partner

Paris

T: +33 1 40 74 68 00

achampsaur@cgsh.com

V-Card

Ferdisha Snagg

Senior Attorney

London

T: +44 20 7614 2251

fsnagg@cgsh.com

V-Card

Clara Cibrario Assereto

Associate

Rome

T: +39 06 6952 2225

ccibrarioassereto@cgsh.com

V-Card