The Current

UK Tax Landscape

for Private Equity

Funds and Professionals

October 2024

The UK tax landscape for private equity funds has appeared increasingly challenging lately – at least in relation to house tax issues and the treatment of deal professionals. With recent announcements made by the newly elected Labour government, that trend looks set to continue.

Set out below is a summary of three key developments for funds to have in mind as the government’s first Budget (due on October 30, 2024) approaches.

Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs) and Salaried Members

Many fund sponsors in the UK have established their management or advisory vehicles as English LLPs, with many deal professionals being members of those LLPs rather than employees. Various UK tax consequences flow from this, including the absence of employer National Insurance contributions in relation to remuneration.

However, since 2014, the UK tax code has contained rules, known as the “salaried member” rules, which are designed to treat certain LLP members, for tax purposes only, as employees where their substantive relationship to the LLP more closely resembles that of an employee rather than a partner.

The rules contain three conditions, each of which must be met for an LLP member to be treated as an employee for tax purposes. Broadly speaking:

Condition A

Is that at least 80% of the total amount payable by the LLP in respect of the relevant member’s performance will be ‘disguised salary’;

Condition B

Is that the relevant member does not have ‘significant influence’ over the affairs of the LLP; and

Condition C

Is that the relevant member’s capital contribution to the LLP in a tax year is less than 25% of their disguised salary from the LLP in that tax year.

There is also a targeted anti-avoidance rule (TAAR) which disregards arrangements – the main purpose, or one of the main purposes, of which is to secure that the relevant member is not treated as a salaried member.

Given the complexity and ambiguity of Conditions A and B, “failing” Condition C has often been relied upon, including in cases where there are arrangements for an LLP member’s capital contribution to be automatically adjusted every year to ensure that it exceeds the 25% threshold. Based on statements made by HMRC at the time the rules were originally introduced, and in light of their original published guidance, reliance upon Condition C has been widely adopted by asset managers, even in cases where individuals were provided with financing to make the relevant capital contributions (so long as the financing did not have non-arm’s length features, like a non‑recourse loan).

In recent months, however, HMRC has begun asserting that arrangements of this kind in the asset management (and certain other) sectors trigger the TAAR, and in February of this year their published guidance was updated to suggest the same. This has caused widespread concern and uncertainty, not only going forwards but also for prior periods.

A number of stakeholders have been making representations to HMRC, urging it to reconsider their approach, in particular for funds that relied upon HMRC’s original practice and published guidance, arguing that HMRC’s revised position is incorrect as a matter of law as well as administratively unfair. HMRC is understood to be conducting an internal review, the outcome of which is keenly anticipated and expected to be imminent.

Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs) and Salaried Members

Many fund sponsors in the UK have established their management or advisory vehicles as English LLPs, with many deal professionals being members of those LLPs rather than employees. Various UK tax consequences flow from this, including the absence of employer National Insurance contributions in relation to remuneration.

However, since 2014, the UK tax code has contained rules, known as the “salaried member” rules, which are designed to treat certain LLP members, for tax purposes only, as employees where their substantive relationship to the LLP more closely resembles that of an employee rather than a partner.

The rules contain three conditions, each of which must be met for an LLP member to

be treated as an employee for tax purposes. Broadly speaking:

Condition A

Is that at least 80% of the total amount payable by the LLP in respect of the relevant member’s performance will be ‘disguised salary’;

Condition B

Is that the relevant member does not have ‘significant influence’ over the affairs of the LLP; and

Condition C

Is that the relevant member’s capital contribution to the LLP in a tax year is less than 25% of their disguised salary from the LLP in that tax year.

There is also a targeted anti-avoidance rule (TAAR) which disregards arrangements – the main purpose, or one of the main purposes, of which is to secure that the relevant member is not treated as a salaried member.

Given the complexity and ambiguity of Conditions A and B, “failing” Condition C has often been relied upon, including in cases where there are arrangements for an LLP member’s capital contribution to be automatically adjusted every year to ensure that it exceeds the 25% threshold. Based on statements made by HMRC at the time the rules were originally introduced, and in light of their original published guidance, reliance upon Condition C has been widely adopted by asset managers, even in cases where individuals were provided with financing to make the relevant capital contributions (so long as the financing did not have non-arm’s length features, like a non‑recourse loan).

In recent months, however, HMRC has begun asserting that arrangements of this kind in the asset management (and certain other) sectors trigger the TAAR, and in February of this year their published guidance was updated to suggest the same. This has caused widespread concern and uncertainty, not only going forwards but also for prior periods.

A number of stakeholders have been making representations to HMRC, urging it to reconsider their approach, in particular for funds that relied upon HMRC’s original practice and published guidance, arguing that HMRC’s revised position is incorrect as a matter of law as well as administratively unfair. HMRC is understood to be conducting an internal review, the outcome of which is keenly anticipated and expected to be imminent.

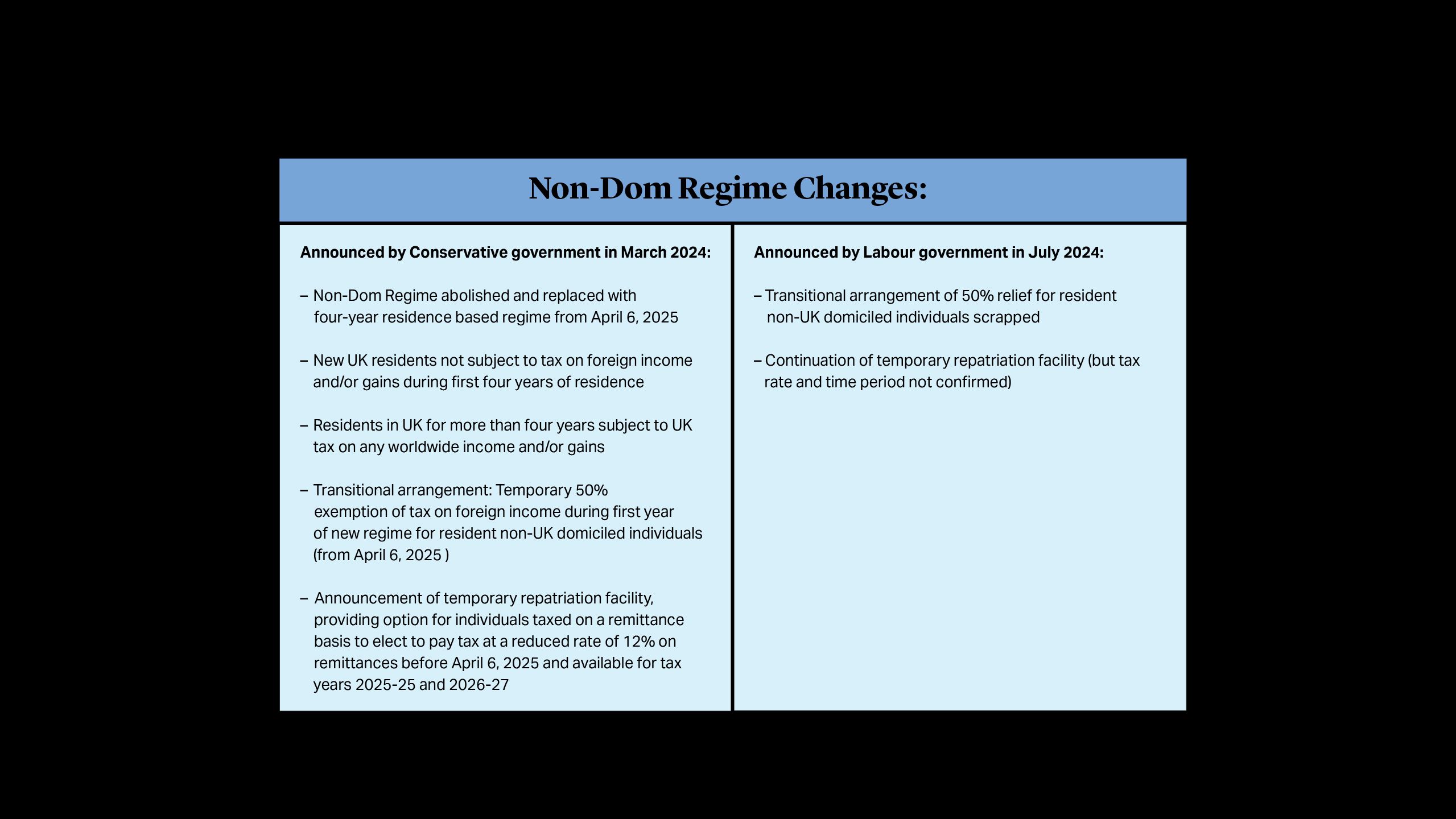

Non-Dom Rules

In March of this year, the previous UK government announced that the current non-dom regime, whereby UK resident individuals domiciled overseas only pay UK tax on non-UK source income and gains remitted to the UK, was to be abolished with effect from April 6, 2025. Under the proposed replacement regime, new UK residents would not be subject to tax on their foreign income or gains for their first four years of residence (whether or not remitted), but anyone who had been resident in the UK for more than four years would be subject to UK tax on all their worldwide income and gains (whether or not remitted). There would also be a number of transitional arrangements, including a temporary 50% exemption from the taxation of foreign income for the first year of the new regime.

Prior to this summer’s general election, the Labour Party confirmed that it too would abolish the non-dom regime, to be replaced with a similar four-year rule. However, the government has actually gone further than the previous administration by scrapping the proposed transitional concession and adopting a more restrictive temporary repatriation facility for individuals who have previously been taxed on the remittance basis, allowing them to remit foreign income and gains that arose prior to April 6, 2025 and pay a reduced tax rate (not yet specified) on such remittance for a limited time period (also not yet specified).

The Labour Party also pledged to take a tougher stance on inheritance tax, moving from a domicile-based regime to a residence-based regime with effect from April 6, 2025. Although the previous government had announced a similar intention, the reforms were to be subject to a formal policy consultation that will now not take place. Full details of the government’s plans are not yet available, but it is envisaged that the basic test for whether non-UK assets are within scope for inheritance tax purposes will be whether a person has been resident in the UK for 10 or more years. It is also expected that non-resident individuals will be in scope if less than 10 years have passed since they previously satisfied the residence test.

Significant announcements were also made about the use of trusts, proposing that all trusts settled by UK resident settlors will be within the scope of UK inheritance tax after the settlor has been UK resident for 10 years, regardless of when the trust was settled.

While not targeted at professionals in the asset management sector, these proposals – coupled with likely changes to carried interest taxation as discussed below – are clearly of keen interest to sophisticated and internationally mobile individuals based in the UK. Further details are expected in the Budget.

Carried Interest

Both prior to and since the general election, the Labour Party has committed to closing what it describes as a “loophole” in the taxation of carried interest, under which (as recently described by HM Treasury) “performance-related reward received by fund managers, primarily within the private equity industry” can “unlike other such rewards…currently be taxed at Capital Gains Tax (CGT) rates of 18% and 28%”.

It has, however, never been entirely clear in which circumstances the Labour Party thought the loophole ought to be closed or how in those circumstances it ought to be closed. The new Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, has communicated a nuanced message by both generally opposing the status quo but also clarifying that where carried interest holders are putting their own capital at risk, it remains “appropriate” that they pay CGT. This uncertainty also sits against a backdrop of rumors that the government is considering general alignment of CGT and income tax rates.

Carried Interest

Both prior to and since the general election, the Labour Party has committed to closing what it describes as a “loophole” in the taxation of carried interest, under which (as recently described by HM Treasury) “performance-related reward received by fund managers, primarily within the private equity industry” can “unlike other such rewards…currently be taxed at Capital Gains Tax (CGT) rates of 18% and 28%”.

It has, however, never been entirely clear in which circumstances the Labour Party thought the loophole ought to be closed or how in those circumstances it ought to be closed. The new Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, has communicated a nuanced message by both generally opposing the status quo but also clarifying that where carried interest holders are putting their own capital at risk, it remains “appropriate” that they pay CGT. This uncertainty also sits against a backdrop of rumors that the government is considering general alignment of CGT and income tax rates.

On July 29 this year, HM Treasury initiated a month-long “call for evidence”, requesting information from stakeholders to feed into the policy design for a new system of taxing carried interest. Specifically, questions were asked as to the most appropriate way for the tax treatment of carried interest to reflect its economic characteristics, the different structures and market practices with respect to carried interest, and the lessons that can be learned from approaches taken in other countries.

While time is short before an inevitable announcement of a new regime in the Budget, it is hoped that the government will allow for further consultation on the details of the new regime and take the opportunity to meet its stated objective of protecting the UK’s position as a world‑leading asset management hub. HM Treasury’s desire in the call for evidence to learn lessons from other countries is consistent with that objective – it might also indicate the kinds of conditions being considered for the new UK regime. Assuming that CGT and income tax rates are not simply going to be aligned, it may well suggest that HMRC is looking at a carried interest tax rate of below 45%, provided holders can satisfy conditions relating to such matters as holding periods and financial commitments, similar to conditions adopted for beneficial tax rates in jurisdictions such as Italy and France.

On July 29 this year, HM Treasury initiated a month-long “call for evidence”, requesting information from stakeholders to feed into the policy design for a new system of taxing carried interest. Specifically, questions were asked as to the most appropriate way for the tax treatment of carried interest to reflect its economic characteristics, the different structures and market practices with respect to carried interest, and the lessons that can be learned from approaches taken in other countries.

While time is short before an inevitable announcement of a new regime in the Budget, it is hoped that the government will allow for further consultation on the details of the new regime and take the opportunity to meet its stated objective of protecting the UK’s position as a world‑leading asset management hub. HM Treasury’s desire in the call for evidence to learn lessons from other countries is consistent with that objective – it might also indicate the kinds of conditions being considered for the new UK regime. Assuming that CGT and income tax rates are not simply going to be aligned, it may well suggest that HMRC is looking at a carried interest tax rate of below 45%, provided holders can satisfy conditions relating to such matters as holding periods and financial commitments, similar to conditions adopted for beneficial tax rates in jurisdictions such as Italy and France.

Looking Ahead

Although these three developments are superficially unconnected, they collectively could have a significant impact on private equity sponsors and professionals in the UK – and they are all coming to a head at the same time. Autumn 2024 looks set to be a critical period for those affected.

This article was prepared with contributions from Cleary associate Thomas Peet.