Disputes within the oil and gas sector are commonplace, and only likely to increase in scope and frequency in the coming decades as the industry seeks to retain its preeminent position within a fast-evolving global energy system. Arbitration often offers the most efficient and expeditious way to resolve these disputes, and enables the parties to have their disputes conclusively resolved in a confidential proceeding by a panel of arbitrators experienced in industry issues.

The early part of the 21st Century has seen drastic changes within the oil and gas industry. The shale boom in North America turned the United States from being a net importer of fossil fuels to a net exporter of oil and gas, with the country overtaking Saudi Arabia and Russia to become the world’s biggest producer of crude oil by the end of the last decade{{1}}{{{Oil and petroleum products explained Where our oil comes from</br>Source: Energy Information Administration}}}.

The rise of the US as an energy power prompted the traditional OPEC nations to forge new alliances with non-OPEC countries, which have in turn led to deals and disruption, some of which has had measurable effects on oil and gas prices.

The early part of the 21st Century has seen drastic changes within the oil and gas industry. The shale boom in North America turned the United States from being a net importer of fossil fuels to a net exporter of oil and gas, with the country overtaking Saudi Arabia and Russia to become the world’s biggest producer of crude oil by the end of the last decade{{1}}{{{Oil and petroleum products explained Where our oil comes from</br>Source: Energy Information Administration}}}.

The rise of the US as an energy power prompted the traditional OPEC nations to forge new alliances with non-OPEC countries, which have in turn led to deals and disruption, some of which has had measurable effects on oil and gas prices.

At the same time, concerns around climate change brought about the 2015 Paris Agreement{{2}}{{{The Paris Agreement: Essential Elements</br>Source: United Nations}}} to limit the increase in global average temperatures since pre-industrial times to below two degrees centigrade. This accord, which has since been signed by more than 180 nations, along with further pressure from governments, investors and consumers around the world, has led several major international oil companies to re-examine their long-term strategies and for some to even strive for net-zero emissions targets by the middle of this century.

In 2020, the combined effects of the Covid-19 pandemic and oversupply of oil after the OPEC-plus deal broke down led to a crash in crude oil prices, causing the price for West Texas Intermediate crude to plunging into negative territory for the first time. These events offer a glimpse of what a world with much-reduced demand for fossil fuels might look like.

This change has served to further focus the minds of oil and gas companies’ boards, several of which are in the process of restructuring business models. For example, several IOCs have revised down markedly their assumptions for long-term oil and gas prices with some European majors now estimating Brent crude to average between $55 and $60 per barrel through to 2050, compared to $75-$90 per barrel before the Covid pandemic struck. Consequently, tens of billions of dollars have been written off from assets owned by these companies.

These trends and events provide the backdrop to an uncertain picture for the oil and gas sector. There is fertile ground for disputes between partners in oil and gas projects, customers and suppliers along oil and gas value chains, as well as governments and the oil and gas corporations they often do business with.

Disputes that occur within the oil and gas sector typically follow a major event that affects demand for energy in a particular country or region, such as a recession, or which has an effect on energy prices. Sudden changes in demand (or supply) in a particular region can have major impacts on the economics of an energy project, and a sudden drop in the price of oil can mean that thousands of oil field developments worldwide can suddenly fail to break even.

Disagreements Between Project Partners

Much activity within the oil and gas industry, particularly in its upstream segment, involves ventures among two or more companies sharing project risks, with each party’s rights and obligations often documented in a Joint Operating Agreement or other similar contract. While this is often a convenient way to ensure the progression of a project, with changes currently taking place within the market, including fluctuation in the prices of oil and gas, the interests of the parties involved in the joint venture may diverge. For example, one of the parties may decide that its money is better invested elsewhere when falling prices put pressure on margins, even though another partner may be heavily reliant on the cash flows from that project. As a result, even where a final investment decision (FID) has been taken to develop a particular oil or gas project, disputes may later arise over its financial viability, including the parties’ respective obligations to continue investing in that venture.

Price Reviews in Long-term Supply Agreements

Long-term agreements for the supply of energy products can often produce disputes if there are major price movements in the wider energy markets. A good example is long-term gas supply agreements. With the price of natural gas often indexed to the price of oil, any significant drop in the price of oil can drive down the spot price for gas. This can lead to a situation where a utility buyer of natural gas would be paying the producer more for the gas than it can charge to its downstream customers. In such cases, the buyer may seek to renegotiate the price it is currently obligated to pay, including pursuant to price review clauses that are often found in long-term agreements, in an effort to reset pricing under the contract. Major disputes in price review cases have arisen, with hundreds of millions, and sometimes billions, of dollars at stake. Competition (antitrust) law can also have a significant impact on these disputes. In the EU, for instance, a party may seek to avoid its obligations under a pricing mechanism by arguing that it infringes Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which restricts cartels and cartel-like agreements that could prevent free competition within the European internal market.

Contract Termination

Significant changes in energy prices can affect the commercial viability of certain activities within the oil and gas value chain. This can lead to affected oil and gas operators attempting to cancel or renegotiate contracts with suppliers and service providers. For example, following the 2014 crash, there was a rash of terminations of multi-year contracts for drilling rigs, which led to several disputes between operators and contractors. The combination of oversupply and overcapacity has also put downward pressure on margins for gas suppliers, leading to arbitrations arising out of efforts to terminate long-term ship-or-pay agreements.

Disputes With, or Related To, Host State Counterparties

More so in Oil and Gas than in other industries, foreign States and State-owned entities are often counterparties with private parties under license and other agreements in the oil and gas sector. Disputes over the failure of construction or development projects or over payments to the State side for royalties, taxes and other payables frequently lead to arbitration, both based on contractual claims, as well as under applicable investment treaties.

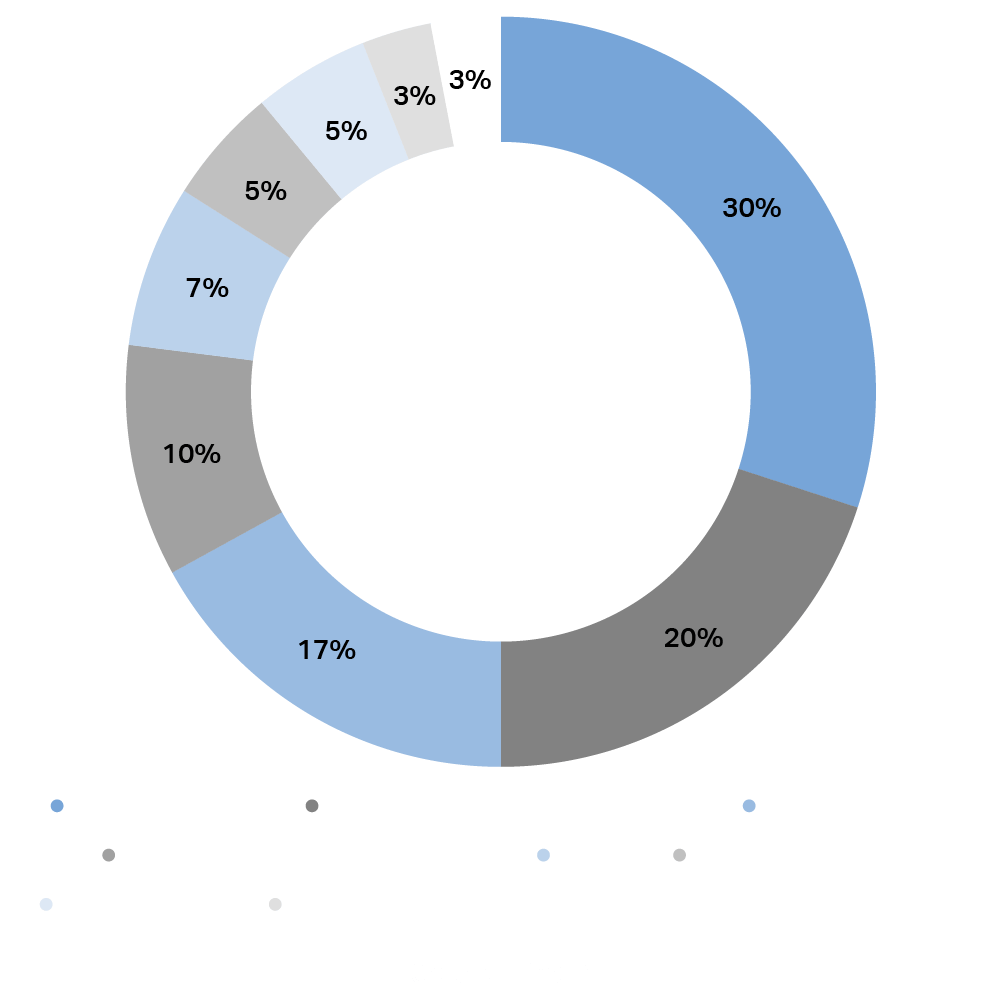

Distribution of New ICSID Cases Registered in FY2020 by Economic Sector

Disputes directly with or under rights conferred by States and State-owned enterprises also has given rise in recent years to the invocation of claims or defences based on corruption (e.g. bribery) during the contracting process.

*{{3}}{{{Vale Wins $2 Billion Arbitration Award Against BSGR Source: Cleary Gottlieb}}}

Disputes Related To Climate Change or Environmental Measures

An increasing number of disputes in the energy sector involve issues related to climate change or the environment. Environmental related disputes may arise out of allegations of losses incurred as a result of climate change or measures taken in the context of the rapidly changing and far reaching transition to energy, land, urban and infrastructure and industrial systems. Environmental related disputes may also arise as components of post-M&A or other claims.

What is Arbitration?

Commercial arbitration is a method by which companies and other organisations agree to resolve disputes without having to go through litigation in a traditional court system.

Contracts and agreements between companies, organisations and governments often include arbitration clauses, so that if a dispute related to the contract does occur, it must be settled via arbitration as opposed to resorting to the court system of one of the parties. An arbitration clause will often set out the agreement of the parties as to the rules that will govern the arbitration, an arbitration institution to administer the proceeding, the number of arbitrators involved (typically three or one), the language to be used in the arbitration, and the ‘seat of arbitration’ (or ‘place’ of arbitration) – typically a neutral location whose arbitration law will govern disputes over procedural issues.

The law of the seat of arbitration can also be important when it comes to challenging or alternatively enforcing any award made. The parties are free to choose a substantive law to govern the rights and obligations under the contract that is different from the law that will govern the arbitration process. If an arbitration clause was not included in the agreement underlying a dispute, the parties in dispute can still elect to have their dispute resolved through arbitration by entering into an “arbitration agreement” after a dispute arises.

What is Arbitration?

Commercial arbitration is a method by which companies and other organisations agree to resolve disputes without having to go through litigation in a traditional court system.

Contracts and agreements between companies, organisations and governments often include arbitration clauses, so that if a dispute related to the contract does occur, it must be settled via arbitration as opposed to resorting to the court system of one of the parties. An arbitration clause will often set out the agreement of the parties as to the rules that will govern the arbitration, an arbitration institution to administer the proceeding, the number of arbitrators involved (typically three or one), the language to be used in the arbitration, and the ‘seat of arbitration’ (or ‘place’ of arbitration) – typically a neutral location whose arbitration law will govern disputes over procedural issues. The law of the seat of arbitration can also be important when it comes to challenging or alternatively enforcing any award made. The parties are free to choose a substantive law to govern the rights and obligations under the contract that is different from the law that will govern the arbitration process. If an arbitration clause was not included in the agreement underlying a dispute, the parties in dispute can still elect to have their dispute resolved through arbitration by entering into an “arbitration agreement” after a dispute arises.

Leading Arbitral Institutions and Centres

- American Arbitration Association, New York, USA

- Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce , Stockholm, Sweden

- Association Française d’Arbitrage , Paris, France

- Australian Centre for International Commercial Arbitration , Melbourne, Australia

- Beijing Arbitration Commission , Beijing, China

- Cairo Regional Centre for International Commercial Arbitration , Cairo, Egypt

- Centro de Arbitraje de México, Mexico City, Mexico

- Chamber of National and International Arbitration Milan, Milan, Italy

- China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission , Beijing, China

- Common Court of Justice and Arbitration , Abidjan, Ivory Coast

- Court of Arbitration of the Polish Chamber of Commerce , Warsaw, Poland

- Court of International Commercial Arbitration Attached to the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Romania , Bucharest, Romania

- Dubai International Arbitration Centre , Dubai

- German Institution of Arbitration , Bonn, Germany

- Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre , Hong Kong

- International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, Washington, D.C., USA

- International Chamber of Commerce , Paris, France

- London Court of International Arbitration , London, UK

- Permanent Court of Arbitration , The Hague, The Netherlands

- Singapore International Arbitration Centre , Singapore

- Swiss Chambers Arbitration Institution , Geneva, Switzerland

- Vienna International Arbitral Centre , Vienna, Austria

- World Intellectual Property Organisation Arbitration and Mediation Centre , Geneva, Switzerland

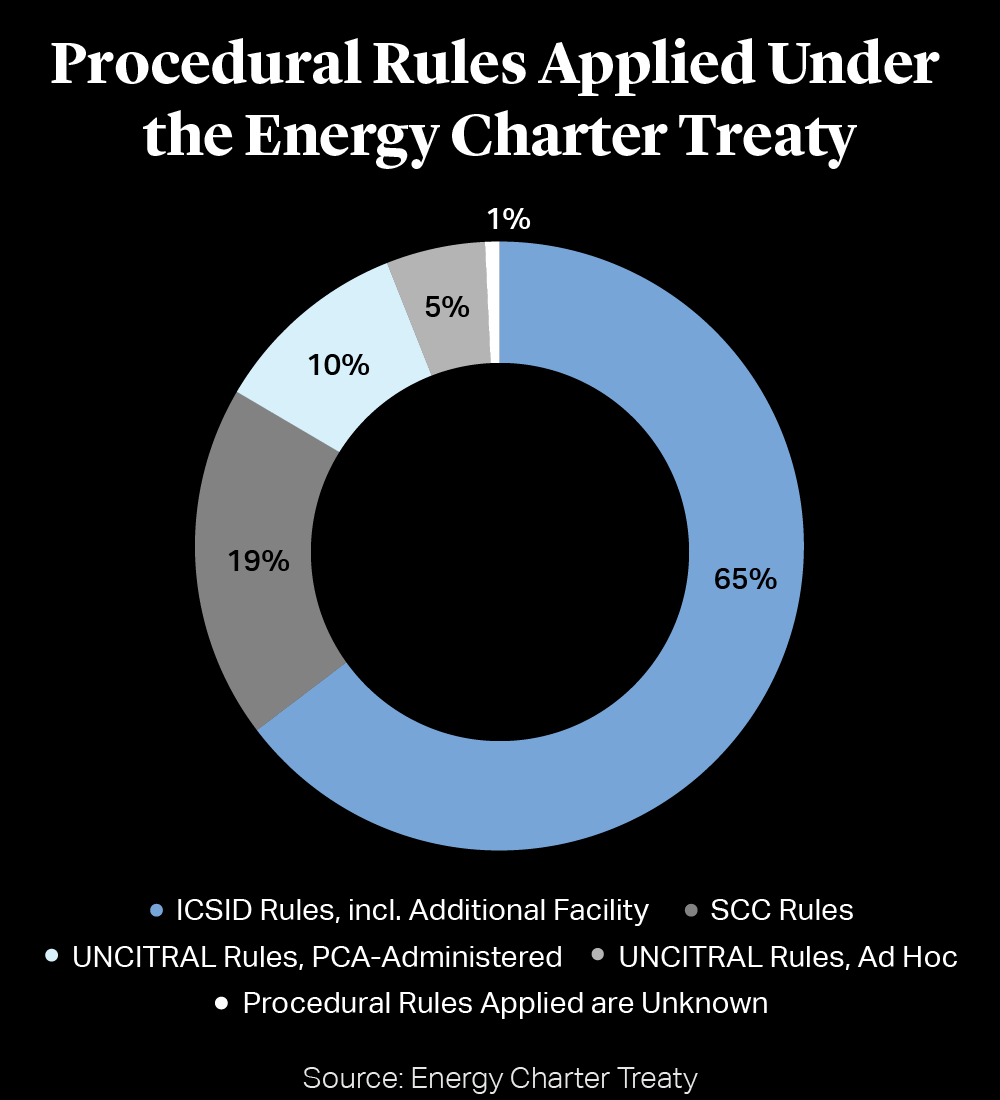

Arbitrations may also arise in the energy sector based on claims under applicable investment treaties. Investors may bring claims against host states by relying on protections afforded to investors in bilateral and multilateral investment treaties, such as the Energy Charter Treaty (“ECT”), a multilateral treaty affording protections to investors in the energy sector. Typical protections afforded to investors under investment treaties include:

- Obligations on host States to afford fair and equitable treatment

- Full protection and security to the investment

- Abstaining from unlawfully expropriating the investment

- Treating foreign investors no less favourably than domestic or third State investors in similar circumstances.

Provided that an investor can demonstrate that they are protected under an investment agreement, they may be able to bring an arbitration against the host State, challenging any conduct that violates the treaty standards. Investment arbitrations typically proceed under the auspices of an arbitration institution, frequently the World Bank’s International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) or may proceed on an ad hoc basis.

The Arbitration Process

In a typical commercial arbitration, the party beginning an arbitration will make a “request for arbitration”, which includes details of the party’s claim. Where the agreement calls for three arbitrators, the claimant will also nominate its proposed arbitrator.

The opposing sides in a dispute will then answer the request for arbitration, assert any counterclaims and select their arbitrator. The parties will seek to agree on a third arbitrator to serve as the chair or president of the arbitral tribunal. In the event they cannot agree, the chair is appointed under the rules of the arbitration institution, such as the London Court of International Arbitration or the International Chamber of Commerce, chosen by the parties in their arbitration clause to administer the arbitration.

The parties then argue their positions, providing evidence to support these. This will normally be done by the parties’ legal representatives. Arguments are submitted in writing, most often followed by a hearing where fact and expert witnesses testify, the arbitrators may pose questions and the lawyers may present oral and/or written closing arguments.

Having then considered the parties’ arguments, the arbitrators will decide the dispute and make an award. Absent extraordinary circumstances or prior agreement to the contrary, when parties have agreed to arbitration, the decision of the arbitrators will be conclusive and not subject to appeal or challenge in court.

The procedure for bringing claims in investment arbitration is broadly similar, under both the ICSID Rules and the Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) that are typically used in investment arbitrations.

A claimant considering whether to bring a claim against a State by initiating an investment treaty arbitration should consider whether the relevant investment treaty includes any admissibility requirements. For instance, treaties may include ‘fork-in-the-road’ clauses, which may provide that the investor must make a choice between pursuing its claims against a host State through the arbitration mechanisms provided in the relevant investment treaties, or in local courts or before other venues provided for in contracts.

In addition, investment treaties frequently provide that an investor and State must, if possible, attempt to settle their dispute by negotiation or conciliation before resorting to investment arbitration. A claimant considering whether to bring an investment treaty arbitration may also need to determine whether specific negotiation obligations or time limits apply under the applicable treaty.

Why Go To Arbitration To Settle a Dispute?

Absent agreement to an alternative form of conclusive dispute resolution, all disputes would otherwise be brought in a national court of a country having jurisdiction over the parties and the subject matter of the dispute. Accordingly, arbitration is often selected by parties to commercial contracts when one sides insists and the other consents or both conclude it has advantages for the parties concerned over the alternative of court litigation:

When companies make agreements with entities hailing from a different jurisdiction, they will often wish to avoid a situation by which they end up arguing a dispute in a court located in the counterparty’s home nation. Arbitration avoids giving one party or the other a ‘home advantage’. For that reason, in cross-border transactions in the oil and gas industry, arbitration, rather than court litigation, is the norm.

Arbitrations are held behind closed doors. In many jurisdictions, such as New York or England and Wales, litigations involving companies, individuals and other entities mean testimony and other kinds of evidence connected to a dispute often become a matter of public record. By contrast, an arbitration can be conducted privately and confidentially, so the parties involved can keep the details of their dispute and commercially sensitive information to themselves.

Many international arbitrators have developed significant subject matter expertise working in the oil and gas sector and resolving substantial oil and gas disputes over the years, and thus often possess substantially more sector-specific expertise than national court judges. This can be important where the resolution of the dispute requires expert testimony from oil and gas experts concerning complex commercial and technical issues unique to the oil and gas sector. While experts are often selected by the parties, the arbitration panel can also appoint its own expert to help reconcile any differences between party-appointed experts.

Arbitration can be relatively speedy and cost efficient. A complex commercial arbitration can take as little time as two-to-three years to complete (and sometimes shorter periods for less complicated disputes).

This is typically as fast as or faster than litigation in a US or European court, and significantly faster than litigation proceedings other regions of the world (e.g. certain jurisdictions in Latin America, it can take more than a decade to settle commercial cases via litigation). Moreover, in arbitration proceedings there is generally less “document discovery”, where parties must disclose to each other the documents in their possession that are relevant to the dispute.

When a commercial dispute goes to litigation in a U.S. or U.K. court (which, given the importance of New York, Texas and English law, are often the forums for oil and gas related litigation), document discovery is a key part of the process.

Investment arbitration in particular provides a means of mitigating against sovereign risks arising out of foreign investment projects, such as expropriation without adequate compensation, the arbitrary revocation of licenses or concessions, and discrimination. Where investors do not have alternative means of bringing claims to challenge a State’s conduct, such as under a contract, investment arbitration is particularly attractive, particularly where the prospect of bringing claims against a State before domestic courts may not be a viable alternative or where the investor is trying to challenge the acts of domestic courts.

To provide the investor with favorable protections under investment treaties and the option of bringing claims in investment arbitration, investors may consider structuring their investments through entities established in countries that have entered into favorable investment treaties with the host State (i.e., the country in which the investment will be made).

Compared to judgments of domestic courts, arbitration awards benefit internationally from a simplified recognition and enforcement mechanism, making the resolution of disputes by arbitration well-suited for disputes between international parties. In the 165 States currently party to the 1958 New York Convention, foreign commercial arbitration awards are in principle recognised as binding and enforceable. The exceptions to this principle of recognition and enforcement that a domestic court may apply are limited, such as invalidity of the arbitration agreement. Similarly, investment treaty arbitration awards issued under the ICSID Convention shall be recognized as binding in the 155 States that are contracting States to the ICSID Convention, and the monetary obligations imposed by ICSID awards shall be enforced, as if the award was a judgment of a domestic court in that State.

What Happens When One Party Challenges an Award?

Under most arbitration clauses found in commercial contracts, the parties agree in advance to be bound by and respect the award issued by the arbitrators. In the majority of cases, arbitration awards are honored and neither side seeks to challenge the award or needs to go to a court to obtain a judgment in order to enforce the award.

One reason for the high rate of voluntary compliance is that a party ordinarily has limited grounds to challenge or vacate the award in a traditional court of law, based on the law at the seat of the arbitration.

The typical seats of international arbitrations, including New York, Geneva, London, and Paris (to name a few), are often hesitant to upset an arbitral award as the grounds for setting aside the award generally cannot be based on a challenge to merits of the decision and instead are typically limited to such issues as fraud in the arbitral process, denial of an opportunity to be heard and to submit evidence, evident partiality or failure of the arbitrator to disclose conflicts of interest, or that the arbitrators exceeded their authority under the parties’ agreement.

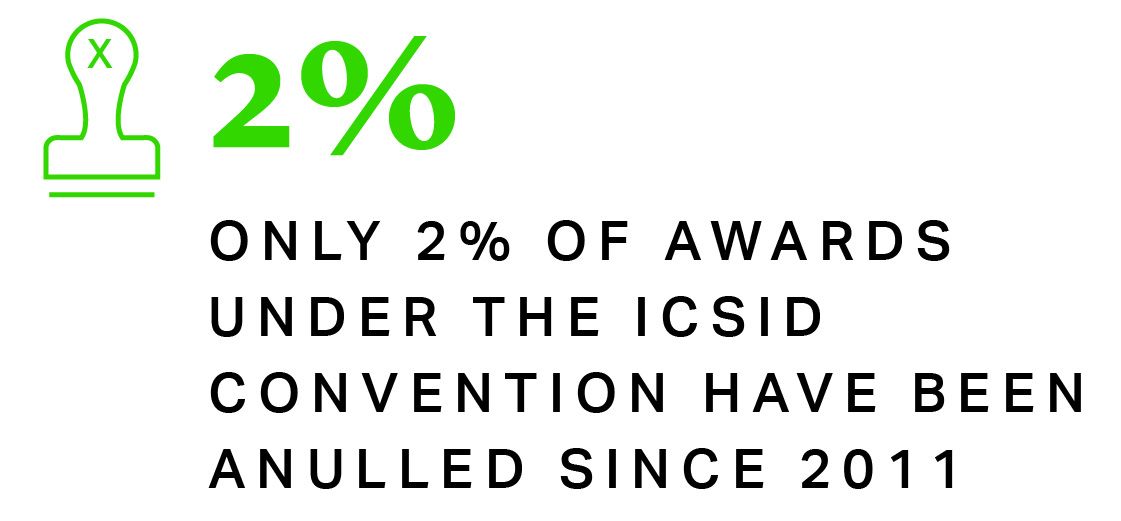

In the context of investment treaty arbitrations, a narrow annulment regime exists in the context of ICSID arbitrations, that allows a party to seek annulment of an ICSID award before an annulment committee on certain limited grounds. Annulment is not an appeals process, but a limited remedy that has been interpreted narrowly. Aside from the self-contained annulment regime for ICSID awards, annulment of non-ICSID awards in investment arbitration must be sought before the courts of the seat of the arbitration, similar to commercial arbitration awards.

The use of arbitrations to resolve disputes appear to be on the rise, with several arbitration institutions reporting increased cases.

For example, the International Chamber of Commerce Court of Arbitration (ICC) saw its second-highest number of cases to date in 2019, with 869 new arbitration cases registered that year. Disputes related to energy companies comprised 16% of new cases at the ICC in 2019, second only to construction (24% of cases){{4}}{{{ London Court of International Arbitration 2019 Annual Casework Report</br>Source: LCIA}}}.

In 2019, there were a record number of cases – 406 – initiated before the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA). The energy and resources sector accounted for the second-highest number of arbitrations, behind the banking and finance sector, with a 22% share – an increase of 3% compared to a 19% share in 2018{{5}}{{{ London Court of International Arbitration 2019 Annual Casework Report</br>Source: LCIA}}}.

In addition, ICSID saw its highest number of cases to date in 2019, during which it administered a total of 306 investment treaty arbitrations brought against States. A significant number of investment treaty arbitrations brought against States under the ICSID rules involved energy and extractives. In 2019, 42% of new cases were related to energy and extractives – equally split between the oil, gas and mining industries, and electric power or other energy sources (21% respectively){{6}}{{{2019 ICSID Annual Report </br>Source: ICSID}}}.

Though there are clear patterns in arbitrations rising, those within the energy and, more specifically, the oil and gas sectors do not always follow this curve for every arbitral institution. In Europe, The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague registered 125 investor-State arbitration cases in 2019, though only eight of those fell under energy or oil and gas (6.4%){{7}}{{{Permanent Court of Arbitration Annual Report 2019</br>Source: Permanent Court of Arbitration}}}, and a similar number (6%) of energy cases were seen by the Swiss Chambers’ Arbitration Institution (SCAI) in the same year{{8}}{{{ Swiss Chambers’ Arbitration Institution 2019 Statistics</br>Source: Swiss Chambers Arbitration Institution}}}. Even fewer energy cases (2%) were registered by the Vienna International Arbitral Centre (VIAC){{9}}{{{ Vienna International Arbitral Centre Annual Report 2019</br>Source: Vienna International Arbitral Centre}}}.

In Asia, the number of energy-related arbitration disputes is also low relative to other sectors, despite overall cases increasing. The Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC) also saw high levels of arbitration cases in 2019 (306 vs. 265 in 2018), but the percentage of those concerning the energy sector was the lowest at just 0.4%{{10}}{{{ Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre 2019 Statistics</br>Source: Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre}}}, and the Korean Commercial Arbitration Board (KCAB)’s caseload for the same year only had 1.1% involving the energy sector{{11}}{{{ Korean Commercial Arbitration Board 2019 Annual Report</br>Source: Korean Commercial Arbitration Board}}}.

Although generally less costly than litigation, companies that may have difficulty funding an arbitration relying on their own resources are increasingly turning to third party funders for assistance.

Junior oil and gas companies, which sometimes depend only on a handful of projects for their cash flows, can be particularly vulnerable if a project goes wrong or there is a falling out with a larger, better-financed partner. However, larger companies may also want to mitigate some of the risk of an arbitration by financing some or all of its costs through third-party funding. Obtaining outside funding for an arbitration may also provide certain accounting benefits for companies; litigation costs are expenditures that must be immediately expensed, meaning they then flow through the P&L and reduce operating profits.

In the short term, investors and stock analysts see only the expense, and not the value that the arbitration may generate in the future. However, when a third-party funder finances a matter, a third party pays the upfront costs and they therefore do not flow through P&L immediately. In the event of a successful outcome, costs are incurred by the party that obtained the funding at the same time as, and offset against, the proceeds resulting from the successful outcome (e.g., in the form of the third party funder being entitled to recover a percentage of the amount awarded); and where the outcome is not successful, the third party funder alone typically bears the costs of the dispute. This means that from an accounting perspective the only impact on financial statements is positive.

Another benefit from working with a partner which specialises in financing arbitrations is to ensure that the award is monetised. Third-party financing can be useful for pursuing unpaid arbitration awards in traditional courts, as can the legal knowledge and experience – across several jurisdictions – of the specialist financing company that is helping to recover the claim.

However, these benefits will come at a cost: companies that agree to fund arbitration-related costs will expect a commercial return, which can be many times their investment.

Although generally less costly than litigation, companies that may have difficulty funding an arbitration relying on their own resources are increasingly turning to third party funders for assistance.

Junior oil and gas companies, which sometimes depend only on a handful of projects for their cash flows, can be particularly vulnerable if a project goes wrong or there is a falling out with a larger, better-financed partner. However, larger companies may also want to mitigate some of the risk of an arbitration by financing some or all of its costs through third-party funding. Obtaining outside funding for an arbitration may also provide certain accounting benefits for companies; litigation costs are expenditures that must be immediately expensed, meaning they then flow through the P&L and reduce operating profits. In the short term, investors and stock analysts see only the expense, and not the value that the arbitration may generate in the future. However, when a third-party funder finances a matter, a third party pays the upfront costs and they therefore do not flow through P&L immediately. In the event of a successful outcome, costs are incurred by the party that obtained the funding at the same time as, and offset against, the proceeds resulting from the successful outcome (e.g., in the form of the third party funder being entitled to recover a percentage of the amount awarded); and where the outcome is not successful, the third party funder alone typically bears the costs of the dispute. This means that from an accounting perspective the only impact on financial statements is positive.

Another benefit from working with a partner which specialises in financing arbitrations is to ensure that the award is monetised. Third-party financing can be useful for pursuing unpaid arbitration awards in traditional courts, as can the legal knowledge and experience – across several jurisdictions – of the specialist financing company that is helping to recover the claim.

However, these benefits will come at a cost: companies that agree to fund arbitration-related costs will expect a commercial return, which can be many times their investment.

The legal financing industry has grown significantly since companies such as the Netherlands’ Omni Bridgeway pioneered the financing of legal risk in the 1980s. Today, there are a number of large legal financing specialists{{12}}{{{ Membership Directory, Association of Litigation Funders</br>Source: Association of Litigation Funders}}}, which provide legal expenses for actions such as arbitrations.

Other legal financing firms take a more active role and are more proactive in how they manage their investments – having a say in which law firms are used, reviewing legal papers before they are submitted and so on – so that they often behave as a senior partner to the claimant in an arbitration. Whether a matter is an appropriate candidate for third party funding will turn on the facts specific to that particular dispute and the particular needs of the party seeking that assistance. But it is clear that third party funding has had a significant impact on the landscape of international arbitration, and that it will likely continue to do so going forward.

A Fast-changing Oil and Gas Landscape is Set To Drive More Disputes

Oil and gas companies are striving for profitability in a world where they expect oil and gas prices may be lower than previously projected. As many oil and gas companies focus on “advantaged”, low-cost and low-emission oil and gas opportunities, while directing a greater proportion of their capital spending toward clean energy projects and emissions mitigation schemes they may reduce investment in other longstanding or more traditional projects.

This could give rise to disputes between project partners. Meanwhile, with significant declines in oil prices occurring in 2014 and 2020, significant fluctuations in energy prices seem to have become more frequent – which may give rise to further disputes along the oil and gas value chain between customers and suppliers. Resource nationalism and anti-corruption campaigns, particularly in Latin America and Africa could be a further source of disputes.

Arbitration Has Become a Preferred Way to Resolve Disputes

Arbitration institutions are registering more commercial arbitrations than ever before, and investment treaty arbitrations also continue to be on the rise. Entities involved in disputes benefit not only from a lower cost and more efficient process than other legal avenues to achieve a resolution, but also benefit from a neutral venue to resolve their dispute, as well as confidentiality.

International arbitration is especially powerful in enabling companies – which may often be long-term contract partners – to resolve a contentious issue with finality. Amid changing times for the oil and gas sector, international arbitration offers a proven, neutral way to reach a final and enforceable decision.

Christopher P. Moore

Partner

London

T: +44 20 7614 2227

New York

T: +1 212 225 2836

cmoore@cgsh.com

V-Card

Ari D. MacKinnon

Partner

New York

T: +1 212 225 2453

amackinnon@cgsh.com

V-Card

Laurie Achtouk-Spivak

Counsel

Paris

T: +33 1 40 74 68 00

lachtoukspivak@cgsh.com

V-Card