In Germany, directors of financially distressed companies must carefully navigate complex legal requirements to avoid personal liability. This article provides an overview of such requirements, highlighting the most important considerations for directors in connection with managing a financially distressed German company.

In Germany, directors of financially distressed companies must carefully navigate complex legal requirements to avoid personal liability. This article provides an overview of such requirements, highlighting the most important considerations for directors in connection with managing a financially distressed German company.

General Duty of Care

German law requires directors of German companies to act with the diligence of a prudent and diligent businessperson managing a company. This broad general diligence requirement comprises numerous specific obligations, including compliance with applicable law, adherence to the company’s articles of association, and the implementation of decisions of the competent corporate body such as the supervisory board or shareholders’ meeting. Although directors generally owe their duties to the company – not the shareholders, creditors, or employees of the company – there are exceptions to this rule, and directors have to take into account the interests of other stakeholders in specific circumstances.

As long as the company is solvent, directors must promote the success and sustainability of the company, which is also in the interests of its shareholders. If the organization becomes financially distressed, preserving the assets of the company in the interests of creditors and ensuring that the company does not engage in (further) detrimental transactions becomes more important. This shift emphasizes the need for directors to balance the interests of various stakeholders while prioritizing the company’s long-term viability.

Directors are obligated to continuously monitor developments that might endanger the company’s continued existence and take appropriate countermeasures if such risks arise. Depending on the size of the company, directors must set up early warning systems to identify potential threats to the financial stability of the company. They are required to immediately report any such threats (such as a loss impairing the stated capital of the company) to their competent supervisory bodies, such as the supervisory board or the shareholders’ meeting.

Insolvency Filing Requirements

The most important guidance for directors of companies in Germany in distress is to never file too late. Directors must file for insolvency within three weeks of the company becoming illiquid and within six weeks if the company is over-indebted. This filing requirement applies not only to companies organized under German law, but to all companies having their center of main interest in Germany, including those organized under non-German law.

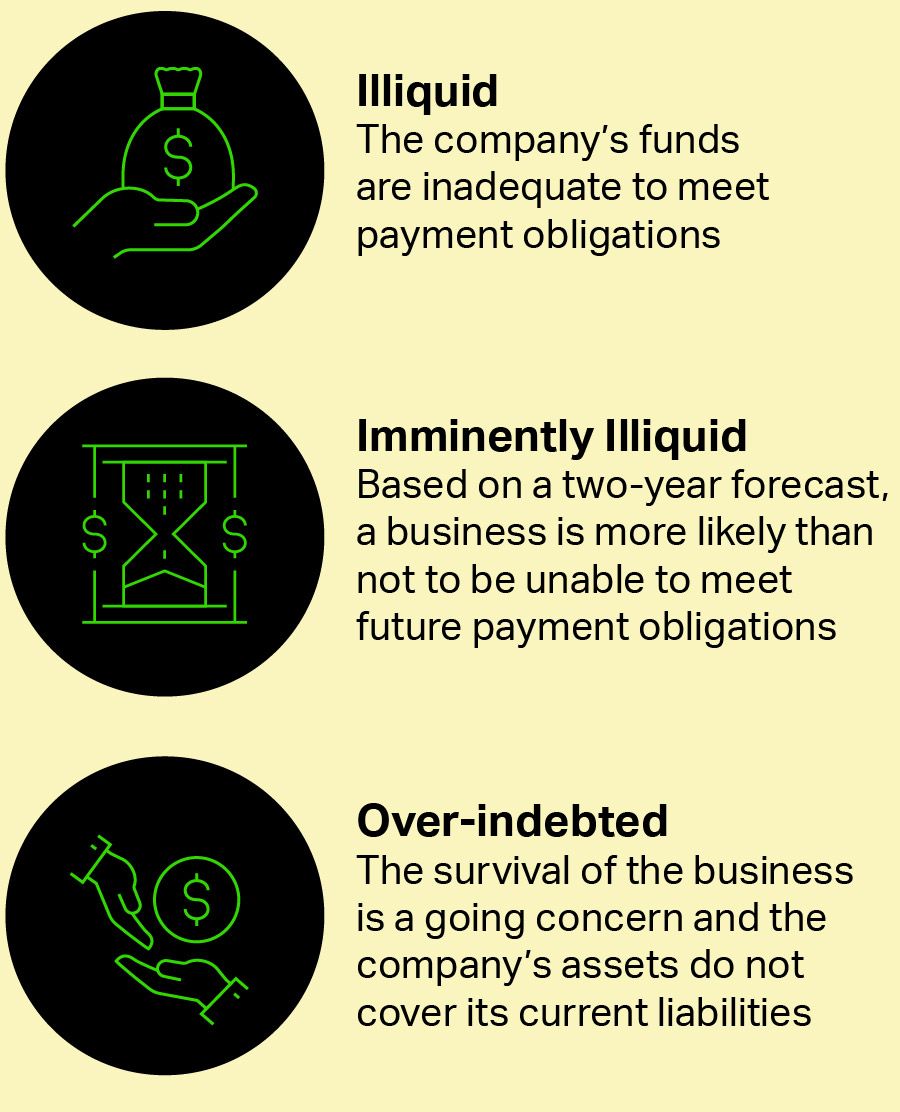

A company is considered illiquid if it is unable to perform its payment obligations as they become due, i.e., if the company’s available funds are permanently inadequate to meet its due payment obligations. This is the case if:

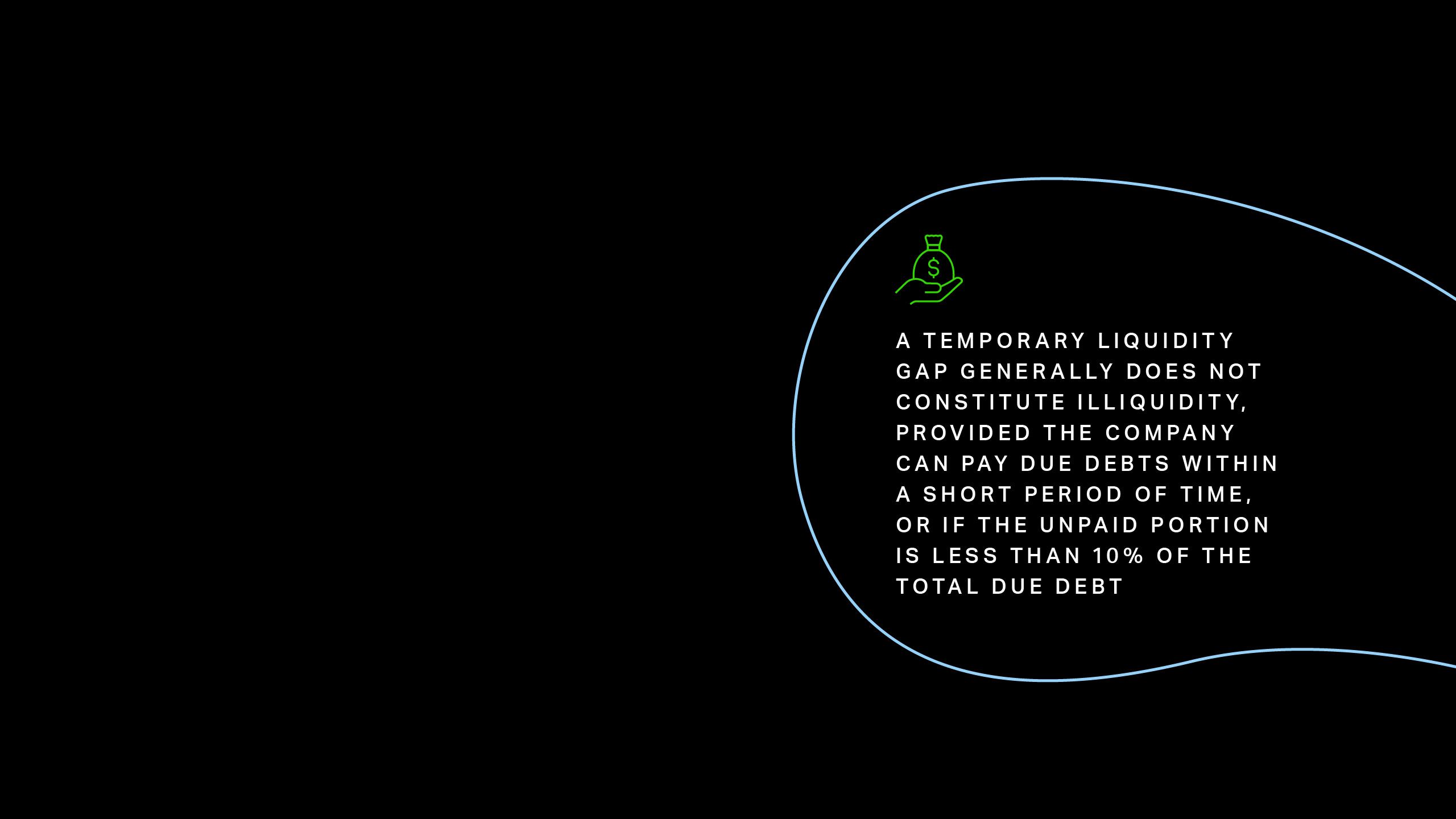

A temporary liquidity gap generally does not constitute illiquidity, provided the company can reasonably expect to pay its due debts within a short period of time, or if the unpaid portion of due debts is less than 10% of the company’s total due debt.

A company is considered over-indebted if the survival of the company’s business as a going concern appears to be rather unlikely (the so-called “outlook test”); and the company’s assets do not cover its current liabilities (the so-called “balance sheet test”). The outlook test is heavily reliant on a forward-looking analysis by management, based upon a realistic and comprehensive assessment of the company’s financial condition and prospects. If the outlook test is negative, the balance sheet test requires the preparation of a special insolvency balance sheet to assess whether the company’s assets at liquidation values cover its liabilities.

Insolvency Filing Requirements

The most important guidance for directors of companies in Germany in distress is to never file too late. Directors must file for insolvency within three weeks of the company becoming illiquid and within six weeks if the company is over-indebted. This filing requirement applies not only to companies organized under German law, but to all companies having their center of main interest in Germany, including those organized under non-German law.

A company is considered illiquid if it is unable to perform its payment obligations as they become due, i.e., if the company’s available funds are permanently inadequate to meet its due payment obligations. This is the case if:

A temporary liquidity gap generally does not constitute illiquidity, provided the company can reasonably expect to pay its due debts within a short period of time, or if the unpaid portion of due debts is less than 10% of the company’s total due debt.

A company is considered over-indebted if the survival of the company’s business as a going concern appears to be rather unlikely (the so-called “outlook test”); and the company’s assets do not cover its current liabilities (the so-called “balance sheet test”). The outlook test is heavily reliant on a forward-looking analysis by management, based upon a realistic and comprehensive assessment of the company’s financial condition and prospects. If the outlook test is negative, the balance sheet test requires the preparation of a special insolvency balance sheet to assess whether the company’s assets at liquidation values cover its liabilities.

In addition, the directors may file the company for insolvency if the company is imminently illiquid. A company is considered imminently illiquid if, based upon a liquidity forecast for a generally two-year period, it appears more likely than not that the company will be unable to meet its future payment obligations. In contrast to the company being illiquid or over-indebted, imminent liquidity does not require the directors to file the company insolvent, but certain actions (such as incurring new debt or making payments) may result in director liability if the company eventually becomes insolvent.

In addition, the directors may file the company for insolvency if the company is imminently illiquid. A company is considered imminently illiquid if, based upon a liquidity forecast for a generally two-year period, it appears more likely than not that the company will be unable to meet its future payment obligations. In contrast to the company being illiquid or over-indebted, imminent liquidity does not require the directors to file the company insolvent, but certain actions (such as incurring new debt or making payments) may result in director liability if the company eventually becomes insolvent.

Reasons for Insolvency Under the German Framework

Reasons for Insolvency Under the German Framework