Green impact investing has so far been predominantly focused on climate change and emissions reduction. Given the remarkable growth and reach of impact investing, - whose market share now surpasses the $1tn mark1– the advantage of diversifying into channels beyond greenhouse gas emissions reduction is now undeniable. Plus, climate change impact is being filled with increasingly complex regulatory requirements. The protection of natural ecosystems and biodiversity could be green funds’ next new frontier.

The link between biodiversity loss and climate change is growing ever clearer. Natural habitats like forests and mangroves sequester carbon, and their loss exacerbates climate change. At the same time, climate change is contributing to the collapse of many ecosystems through rising temperatures and extreme weather patterns.

As well as its dangerous potential to cause wider devastation to nature, biodiversity loss has been shown to pose significant financial risk to countries, supply chains and the global economy. Healthy biodiversity is pivotal to our global supply chains and our ability to source food, clean water and essential services. Nature brings $150tn into the global economy each year, and an estimated $44tn – more than half of global GDP – depends on it2. By all metrics, the health of biodiversity is intrinsically linked to the success of our global markets.

As governments, supervisors, and financial institutions begin to take note, what opportunities could this shift of focus from climate to nature represent for ESG-minded investors and asset managers?

The link between biodiversity loss and climate change is growing ever clearer. Natural habitats like forests and mangroves sequester carbon, and their loss exacerbates climate change. At the same time, climate change is contributing to the collapse of many ecosystems through rising temperatures and extreme weather patterns.

As well as its dangerous potential to cause wider devastation to nature, biodiversity loss has been shown to pose significant financial risk to countries, supply chains and the global economy. Healthy biodiversity is pivotal to our global supply chains and our ability to source food, clean water and essential services. Nature brings $150tn into the global economy each year, and an estimated $44tn – more than half of global GDP – depends on it2. By all metrics, the health of biodiversity is intrinsically linked to the success of our global markets.

As governments, supervisors, and financial institutions begin to take note, what opportunities could this shift of focus from climate to nature represent for ESG-minded investors and asset managers?

Holland’s Central Bank (the DNB) was the first central bank to recognize and highlight the financial risks posed by biodiversity loss. Its landmark 2020 study, Indebted to Nature, estimated biodiversity loss created exposure in over a third of the assets across Dutch banks, pension funds and insurers that were assessed3. France, Brazil, Malaysia and Mexico are among the countries whose central banks followed DNB’s lead, with similar findings.

Within the global economy, emerging markets (including sovereign issuers) are particularly vulnerable. This is because they rely more on nature services like wild pollination, and often lack the finances to mitigate the effects of climate change. At the same time, they safeguard some of the world’s most precious areas for biodiversity.

Despite the clear economic case for the contrary, addressing this biodiversity loss is often ignored. The issue is regularly viewed as “too complicated” to tackle4, and there are legitimate concerns over greenwashing – particularly in relation to the controversial practice of carbon offsetting. A 2022 HSBC survey found over half of investor-respondents were not actively looking at biodiversity investments5.

Holland’s Central Bank (the DNB) was the first central bank to recognize and highlight the financial risks posed by biodiversity loss. Its landmark 2020 study, Indebted to Nature, estimated biodiversity loss created exposure in over a third of the assets across Dutch banks, pension funds and insurers that were assessed3. France, Brazil, Malaysia and Mexico are among the countries whose central banks followed DNB’s lead, with similar findings.

Within the global economy, emerging markets (including sovereign issuers) are particularly vulnerable. This is because they rely more on nature services like wild pollination, and often lack the finances to mitigate the effects of climate change. At the same time, they safeguard some of the world’s most precious areas for biodiversity.

Despite the clear economic case for the contrary, addressing this biodiversity loss is often ignored. The issue is regularly viewed as “too complicated” to tackle4, and there are legitimate concerns over greenwashing – particularly in relation to the controversial practice of carbon offsetting. A 2022 HSBC survey found over half of investor-respondents were not actively looking at biodiversity investments5.

The 2015 Paris Agreement has been heralded as a sea change moment in the fight against climate change. Through the treaty, world governments agreed on a common language and framework for climate-related activities.

Biodiversity and nature protection is yet to reach this milestone. At COP26, language on biodiversity or “nature-based solutions” was removed from the Glasgow Climate Pact6. Finally, the tide may be changing: the World Biodiversity Summit (WBS), to be held in Montreal this month, is expected to create a Paris-style agreement for biodiversity.

Action is also already being taken to assess how to correct biodiversity loss, and the risks it poses to financial institutions. This year, the central bankers’ Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and the International Network for Sustainable Financial Policy Insights, Research, and Exchange (INSPIRE) published a joint report, proposing measures for central banks to tackle biodiversity loss. Recommended best practices include nature-related stress tests (to be used alongside the better-established climate-related stress tests)7. The Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosure (TFND) is also set to release a global baseline regulatory framework on biodiversity in 20238.

The 2015 Paris Agreement has been heralded as a sea change moment in the fight against climate change. Through the treaty, world governments agreed on a common language and framework for climate-related activities.

Biodiversity and nature protection is yet to reach this milestone. At COP26, language on biodiversity or “nature-based solutions” was removed from the Glasgow Climate Pact6. Finally, the tide may be changing: the World Biodiversity Summit (WBS), to be held in Montreal this month, is expected to create a Paris-style agreement for biodiversity.

Action is also already being taken to assess how to correct biodiversity loss, and the risks it poses to financial institutions. This year, the central bankers’ Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) and the International Network for Sustainable Financial Policy Insights, Research, and Exchange (INSPIRE) published a joint report, proposing measures for central banks to tackle biodiversity loss. Recommended best practices include nature-related stress tests (to be used alongside the better-established climate-related stress tests)7. The Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosure (TFND) is also set to release a global baseline regulatory framework on biodiversity in 20238.

As on many ESG-related fronts, the EU is positioning itself as a frontrunner on biodiversity regulation.

The EU’s “Biodiversity Strategy for 2030” lays out a comprehensive long-term plan to protect nature and reverse the degradation of ecosystems, aiming to put Europe’s biodiversity on a path to recovery9.

The Strategy focuses on improving financial supervisors and businesses’ awareness, and increasingly factoring nature into business and public decisions. The overall aim is to cause EU-based businesses to consider the nature-related impacts of their supply chains.

As on many ESG-related fronts, the EU is positioning itself as a frontrunner on biodiversity regulation.

The EU’s “Biodiversity Strategy for 2030” lays out a comprehensive long-term plan to protect nature and reverse the degradation of ecosystems, aiming to put Europe’s biodiversity on a path to recovery9.

The Strategy focuses on improving financial supervisors and businesses’ awareness, and increasingly factoring nature into business and public decisions. The overall aim is to cause EU-based businesses to consider the nature-related impacts of their supply chains.

Things seem to be moving not only from a regulatory perspective.

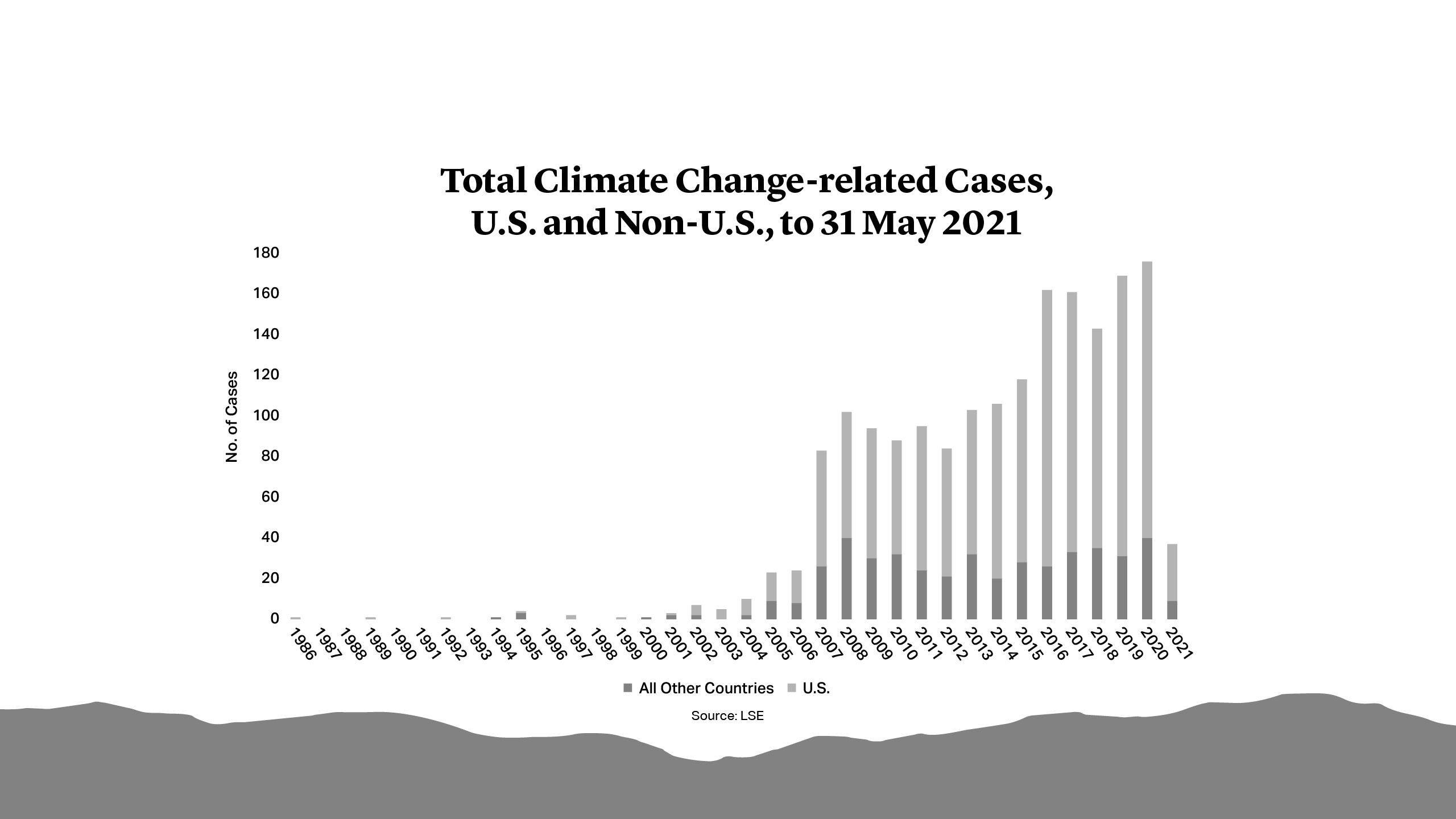

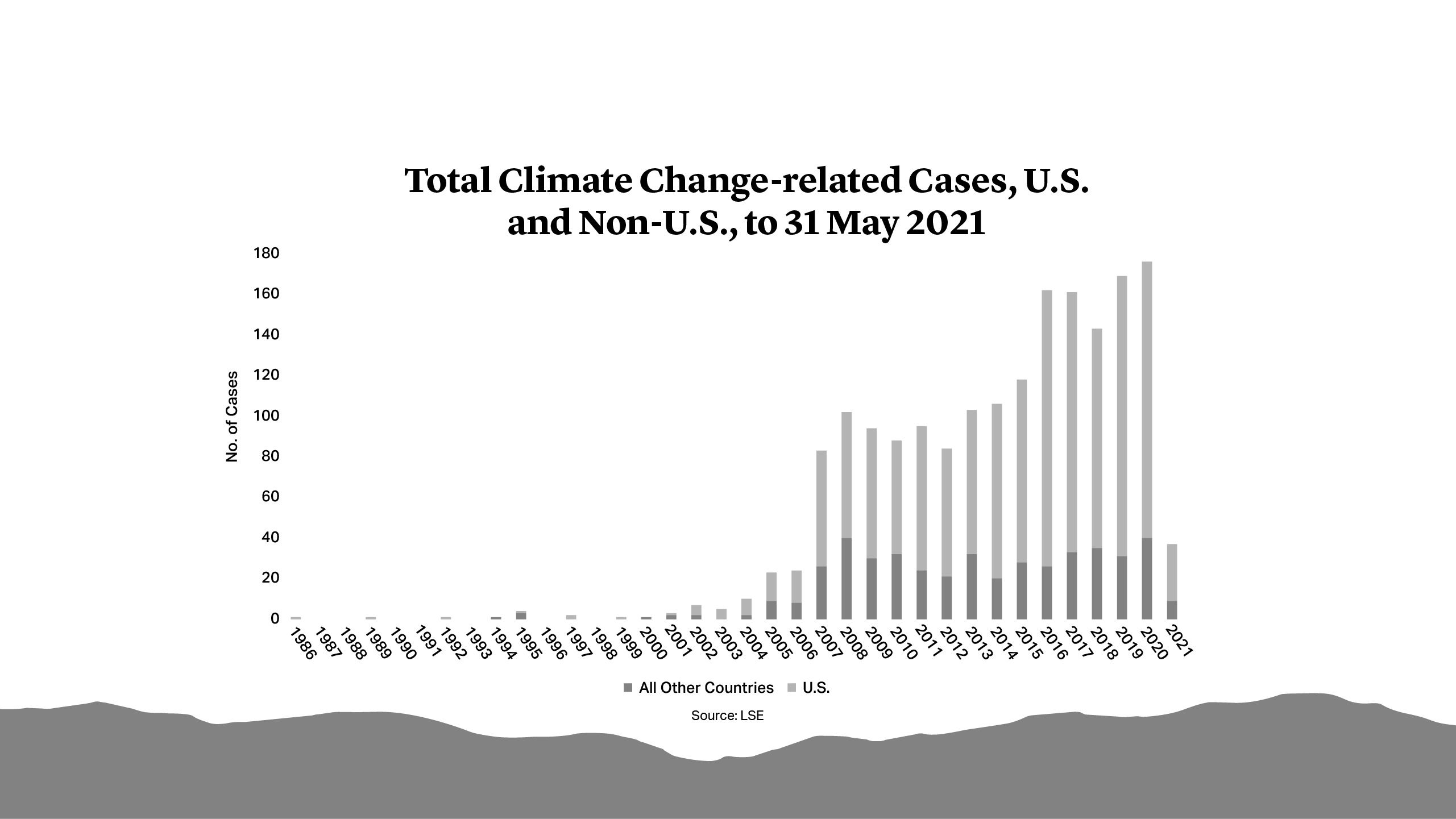

The Paris Agreement triggered an instant spike in climate change-related litigation. Just over 800 climate-related cases were filed in the 20 years before the Treaty’s signing. The number grew by over 1,000 in just the following five years10. Private companies are increasingly targeted11.

If countries reach an agreement on biodiversity in Montreal this year, biodiversity litigation may similarly rise.

One example is the ground-breaking court action brought against French supermarket chain Casino in 2021 by 11 indigenous groups of the Amazon. Leveraging France’s 2017 “Duty of Vigilance” law, the plaintiffs are accusing the multinational of selling meat linked to deforestation, land-grabbing and violence against local communities in Brazil and Colombia12.

Environmental justice is likely to cast very wide nets. It is far easier to establish a causal link between an oil spill and the harm caused to local communities than it is to hold specific oil majors responsible for their contribution to climate change13. Similar lawsuits have succeeded in the past. In 2020, a Chinese NGO won a landmark case in the high court of Yunnan Province in South West China, stopping the construction of a partially completed hydropower station on the Jiasa river – the habitat of the endangered green peacock.

Increasingly, courts around the world have also shown inclination to recognize nature on its own legal standing. Since 2017, courts in New Zealand, India, Bangladesh and Spain have granted legal standing to their national rivers14. Ecuador and Bolivia enshrined similar principles in their national Constitutions. Rising risk of this kind will soon turn businesses’, regulators’, and also investors’ attention to nature.

Things seem to be moving not only from a regulatory perspective.

The Paris Agreement triggered an instant spike in climate change-related litigation. Just over 800 climate-related cases were filed in the 20 years before the Treaty’s signing. The number grew by over 1,000 in just the following five years10. Private companies are increasingly targeted11.

If countries reach an agreement on biodiversity in Montreal this year, biodiversity litigation may similarly rise.

One example is the ground-breaking court action brought against French supermarket chain Casino in 2021 by 11 indigenous groups of the Amazon. Leveraging France’s 2017 “Duty of Vigilance” law, the plaintiffs are accusing the multinational of selling meat linked to deforestation, land-grabbing and violence against local communities in Brazil and Colombia12.

Environmental justice is likely to cast very wide nets. It is far easier to establish a causal link between an oil spill and the harm caused to local communities than it is to hold specific oil majors responsible for their contribution to climate change13. Similar lawsuits have succeeded in the past. In 2020, a Chinese NGO won a landmark case in the high court of Yunnan Province in South West China, stopping the construction of a partially completed hydropower station on the Jiasa river – the habitat of the endangered green peacock.

Increasingly, courts around the world have also shown inclination to recognize nature on its own legal standing. Since 2017, courts in New Zealand, India, Bangladesh and Spain have granted legal standing to their national rivers14. Ecuador and Bolivia enshrined similar principles in their national Constitutions. Rising risk of this kind will soon turn businesses’, regulators’, and also investors’ attention to nature.

Polina Lyadnova

Partner

London

T: +44 20 7614 2355

plyadnova@cgsh.com

V-Card

Jim Ho

Partner

London

T: +44 20 7614 2284

jho@cgsh.com

V-Card