In Part I, we examined how in-court restructurings in Brazil, Mexico, Chile and Argentina fared in comparison to those in the U.S. in terms of case duration. In this second article, we discuss some potential explanations for why durations of bankruptcy proceedings vary so significantly between Latin American jurisdictions and the U.S.

The reasons behind delays will, of course, vary from country to country and from company to company. However, there are certain trends in Latin American bankruptcy proceedings that, when compared to Chapter 11, make them more likely to drag on. For instance, for various reasons, Latin American companies are less likely to pre-negotiate with creditors before filing1.

Differences in insolvency law also play a part. For example, there is no requirement in the U.S. that companies be insolvent to declare bankruptcy – they simply have to be experiencing financial distress. This means that companies can choose to restructure earlier, when they are more likely to have the ability to recover quickly. By contrast, jurisdictions like Mexico impose certain requirements, such as levels of debt and defaults, that a company needs to meet in order to qualify for bankruptcy.

Various Latin American bankruptcy codes still contain significant uncertainty regarding key bankruptcy topics, such as substantive consolidation and voting rules. Many cannot address ‘extrajudicial claims’ (i.e., claims that by law cannot be impaired by a bankruptcy proceedings), do not permit the sale of assets without creditor approval as to how the proceeds will be distributed, and/or typically allow for less flexibility regarding the classification of creditors for voting and plan treatment purposes.

To take advantage of Chapter 11, a company does not need substantial operations in the U.S., as Chapter 11 eligibility is based on the requirement that a company “resides or has a domicile, a place of business, or property” in the country (11 U.S.C. § 109(a)). A common strategy for foreign companies is to file bankruptcy proceedings based on “property” located in the U.S., even if such assets are minimal (e.g., receivables owed by U.S. counterparties, U.S. bank accounts and prospective debtors’ funds held in a lawyer’s retainer account)2.

Additionally, during Chapter 11 proceedings, management is generally allowed to continue running the company and the debtor normally continues to control its assets and run its operations as a debtor-in-possession (DIP), except under extraordinary circumstances (e.g., fraud or mismanagement)3. Such continuation and retention of expertise may make the company more likely to recuperate faster. In contrast, other jurisdictions may replace management with independent trustees or require courts to consent to management’s actions. In Argentina, for instance, once a bankruptcy judgment has been issued, the appointment of a court expert is mandatory, and in Brazil the prosecutor general has much broader powers than the U.S. trustee does in a Chapter 11 case.

Court specialization and process also plays a big part in the length of restructuring proceedings. Chapter 11 judges have specialized expertise that allows them to parse through complex corporate bankruptcy issues and deal with sophisticated parties more quickly. Court specialization also produces an extensive record of precedents that gives certainty to debtors and creditors regarding key bankruptcy issues, thus making the process more efficient.

Local courts in Latin America, on the other hand, tend to not have the same level of expertise. In Brazil, for instance, only a few states have specialized bankruptcy courts (e.g., Minas Gerais). In Argentina, since there are no specialized courts for bankruptcy, distressed companies need to resort to commercial courts, which tend not to operate efficiently or rule uniformly. Furthermore, the widespread use of constitutional challenges (amparos) to challenge insolvency proceedings in many Latin American jurisdictions results in longer processes compared to the U.S., where constitutional challenges to bankruptcy proceedings are narrowly circumscribed.

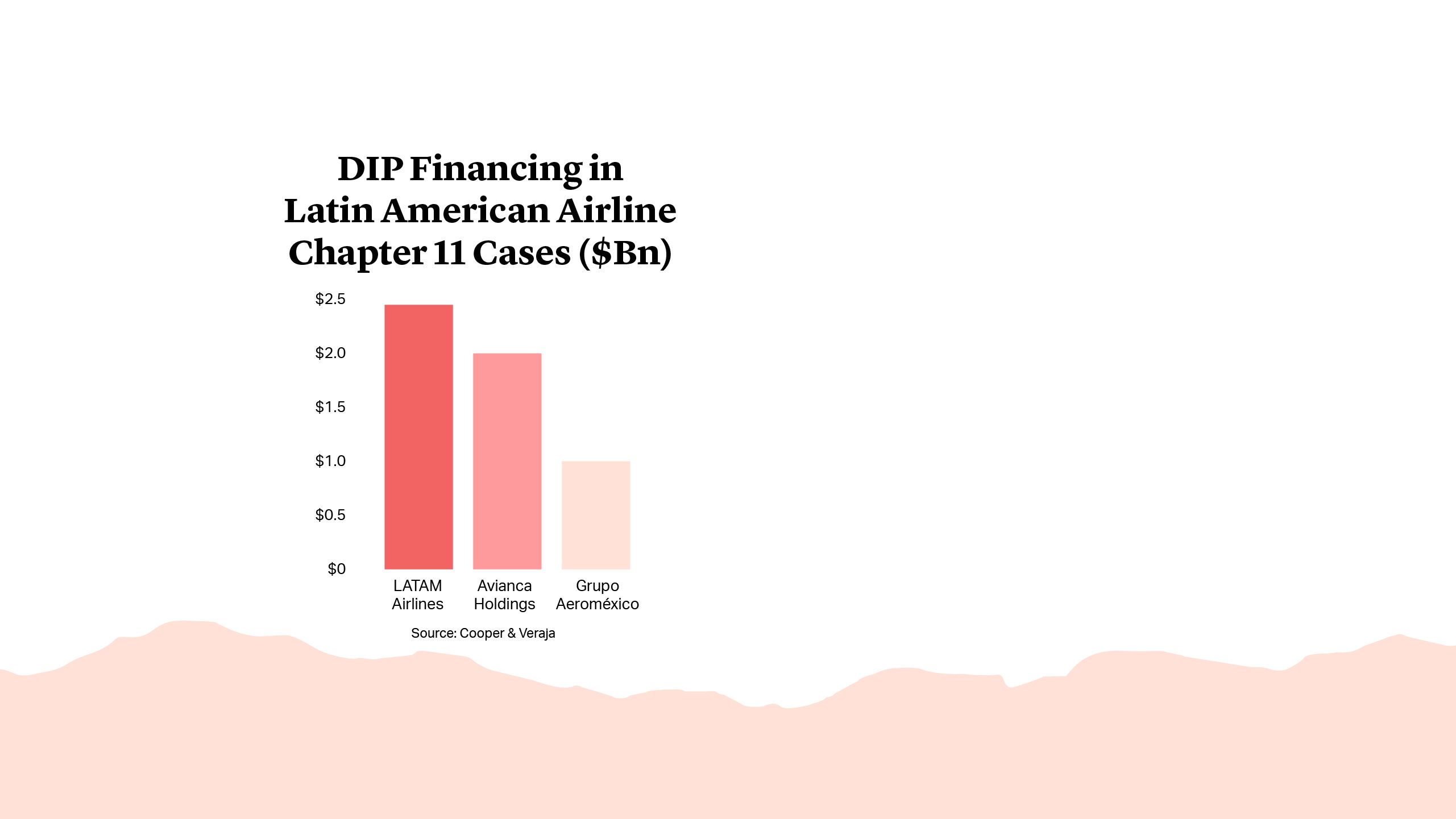

Another unique aspect of Chapter 11 that makes the bankruptcy process appealing to companies around the world is the availability of efficient DIP financing. In the U.S., the bankruptcy law allows debtors in distress to borrow additional money so that they can continue their operations and more quickly emerge from bankruptcy. Debtors are required to obtain approval from the bankruptcy court for such borrowings. In recent years, several Latin American corporations have been authorized to receive substantial DIP financing, including LATAM Airlines ($2.45bn), Avianca Holdings ($2bn) and Grupo Aeroméxico ($1bn)4. In certain other jurisdictions, the bankruptcy law and other regulations (including banking regulations) tend to discourage lending to insolvent entities, thus prolonging insolvency. For example, in Mexico, although DIP financing is possible, financial regulations require that banks score potential borrowers based on their current capacity to meet financial obligations, essentially ruling out bankrupt entities. In Brazil, although reforms from January 2021 introduced additional features designed to encourage the use of DIP financing, such as heightened priority and certain protections from appeals, it still lacks many important features of the U.S. DIP financing model, such as the possibility to prime pre-petition secured creditors.

Along the same lines, in Chapter 11 proceedings, the debtor is generally authorized to sell some or all of its assets free and clear of existing liens and claims, generally attaching any security interest in the assets sold to the proceeds of the sale, subject to certain requirements (11 U.S.C. § 363). These bankruptcy sales can be relatively expeditious, some settling in two to four months or less, depending on the case5. In countries like Argentina, on the other hand, expediency in bankruptcy sales is highly unusual since, as a rule, they occur during the liquidation stage when the company has already ceased to operate.

Cultural differences may also play a role. Corporate bankruptcy in the U.S. is not necessarily seen as a defeat or embarrassment; rather, it may be seen as an opportunity to emerge from financial difficulty.

Bankruptcy in Latin America, on the other hand, tends to be equated with failure. As a result, while one of the goals of Chapter 11 is to provide the bankrupt debtor with tools to succeed, in Latin American jurisdictions, bankruptcy laws tend to limit the debtor’s opportunities, looking down on it with mistrust.

Bureaucracy, of course, plays a part. For example, Chapter 11 protects debtors from the moment that a bankruptcy application is submitted, automatically enjoining all creditor actions against the debtor. This is rarely the case in other jurisdictions. In Mexico, unless the case has been pre-negotiated, debtors generally need to wait for a third party to deliver a report and for the court to approve the stay. In Argentina, although the automatic stay does exist, it needs to go through certain administrative procedures in order to become effective.

Notwithstanding the above, it’s important to note that the appealing features of Chapter 11 may be overshadowed by a low likelihood of enforcement in some Latin American countries. In the case of Brazil, for example, it is less likely for a company whose principal place of business is in Brazil to file for bankruptcy in the U.S. considering that there are several local sources of credit who could challenge a proceeding.

At the same time, when it comes to the timing of restructuring proceedings in Latin America, Chile is a notable exception. In fact, bankruptcy proceedings in Chile tend to be much quicker than Chapter 11 proceedings. The main explanation for this outcome is likely that, in 2014, Chile enacted a new bankruptcy law that was partly aimed at making bankruptcy proceedings faster and more efficient. Another explanation may be that the current Chilean insolvency law is relatively new and has only been applied to a few companies.

Cultural differences may also play a role. Corporate bankruptcy in the U.S. is not necessarily seen as a defeat or embarrassment; rather, it may be seen as an opportunity to emerge from financial difficulty.

Bankruptcy in Latin America, on the other hand, tends to be equated with failure. As a result, while one of the goals of Chapter 11 is to provide the bankrupt debtor with tools to succeed, in Latin American jurisdictions, bankruptcy laws tend to limit the debtor’s opportunities, looking down on it with mistrust.

Bureaucracy, of course, plays a part. For example, Chapter 11 protects debtors from the moment that a bankruptcy application is submitted, automatically enjoining all creditor actions against the debtor. This is rarely the case in other jurisdictions. In Mexico, unless the case has been pre-negotiated, debtors generally need to wait for a third party to deliver a report and for the court to approve the stay. In Argentina, although the automatic stay does exist, it needs to go through certain administrative procedures in order to become effective.

Notwithstanding the above, it’s important to note that the appealing features of Chapter 11 may be overshadowed by a low likelihood of enforcement in some Latin American countries. In the case of Brazil, for example, it is less likely for a company whose principal place of business is in Brazil to file for bankruptcy in the U.S. considering that there are several local sources of credit who could challenge a proceeding.

At the same time, when it comes to the timing of restructuring proceedings in Latin America, Chile is a notable exception. In fact, bankruptcy proceedings in Chile tend to be much quicker than Chapter 11 proceedings. The main explanation for this outcome is likely that, in 2014, Chile enacted a new bankruptcy law that was partly aimed at making bankruptcy proceedings faster and more efficient. Another explanation may be that the current Chilean insolvency law is relatively new and has only been applied to a few companies.

Ineffective debt recovery systems create a higher cost of capital and increase the perception of risk among investors and financial institutions. This can prevent viable businesses from continuing to function when in a state of insolvency6, and even lead to bank failures, with the potential to become a significant threat to the stability of the financial sector as a whole7.

As Latin American insolvency regimes mature, precedents accumulate and bankruptcy reforms continue to be implemented, one can cautiously hope that Latin American case durations will converge to those of the U.S. over time. Nevertheless, given how entrenched some of the factors that cause the process to move slowly in the first place are in some of these jurisdictions, we do not expect to see any Sungard-type precedents8, where a prepackaged bankruptcy case was confirmed just 19 hours after being filed – the current record holder in the U.S. In these countries, progress in reducing bankruptcy case timelines, much like the proceedings themselves, is likely to remain slow.

Marcelo Messer

Managing Director

Rothschild & Co

Richard J. Cooper

Partner

New York

T: +1 212 225 2276

rcooper@cgsh.com

V-Card

Maria (Kiki) Manzur

Associate

New York

T: +1 212 225 2217

mmanzur@cgsh.com

V-Card