The Decline of

Non-Bank Financial

Institutions

in Latin America

Well-known multinational companies, growing national champions and state-owned enterprises in Latin America have a relatively easy time accessing bank credit, as commercial banks in the region provide them loans on good terms due to strong company credentials and low risk profiles.

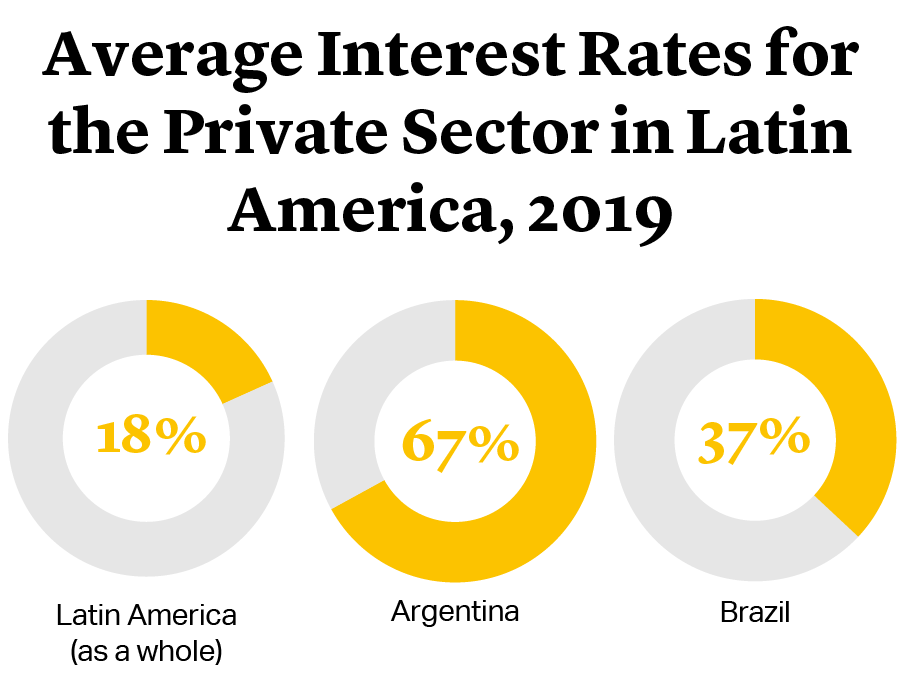

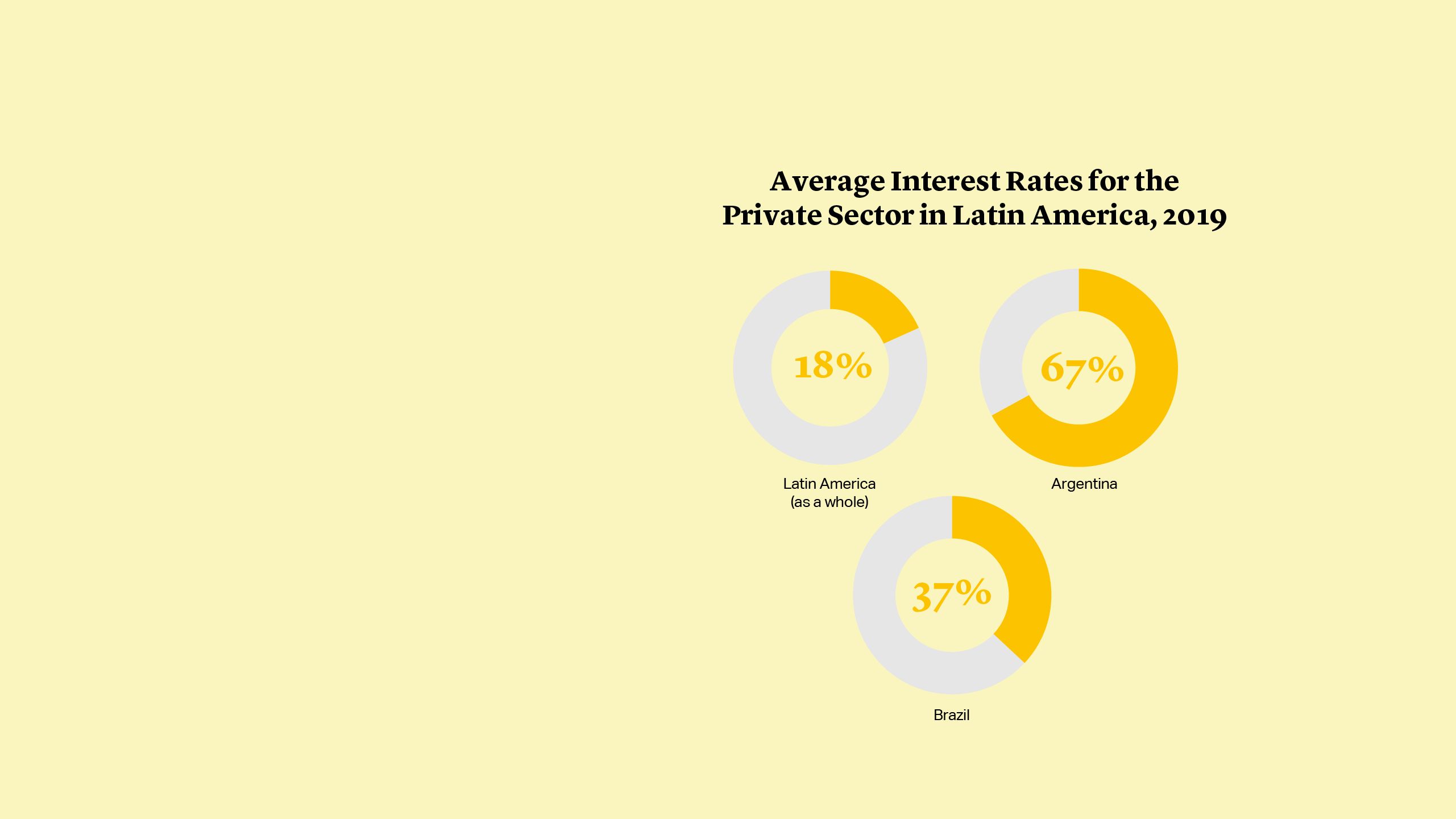

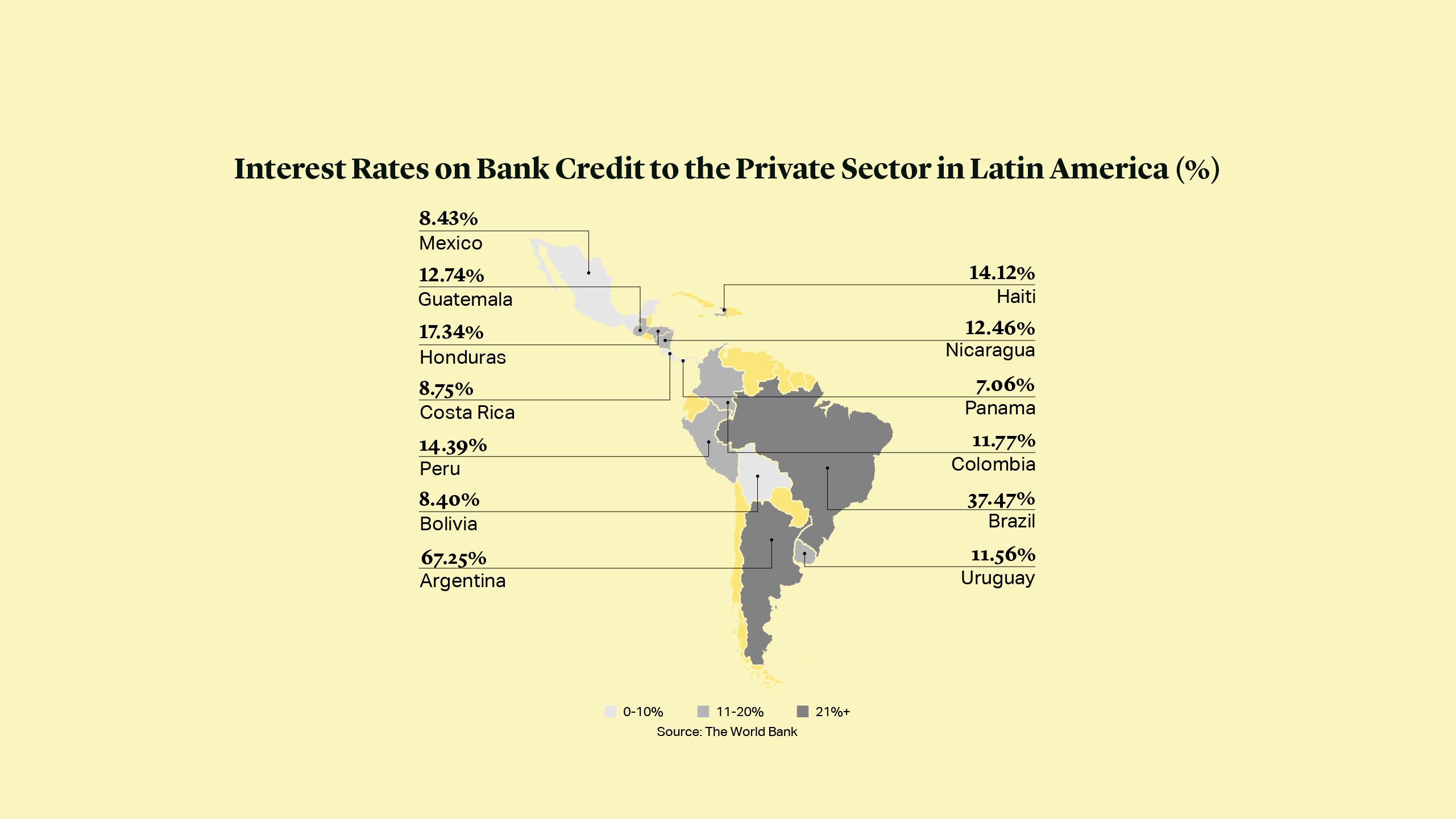

Consumers and micro, small to medium sized enterprises, however, are not afforded the same luxury. Instead, commercial banks offer them high interest rates for low-value, short-term loans, given the high risk attached to consumer lending in the region. Average interest rates for the private sector in Latin America as a whole were 18% in 2019, while in Argentina and Brazil individually, the average was 67% and 37% respectively1. Some banks in the region are known to offer rates as high as 140% per annum, pushing many consumers out of the commercial banking sector all together.

Well-known multinational companies, growing national champions and state-owned enterprises in Latin America have a relatively easy time accessing bank credit, as commercial banks in the region provide them loans on good terms due to strong company credentials and low risk profiles.

Consumers and micro, small to medium sized enterprises, however, are not afforded the same luxury. Instead, commercial banks offer them high interest rates for low-value, short-term loans, given the high risk attached to consumer lending in the region. Average interest rates for the private sector in Latin America as a whole were 18% in 2019, while in Argentina and Brazil individually, the average was 67% and 37% respectively1. Some banks in the region are known to offer rates as high as 140% per annum, pushing many consumers out of the commercial banking sector all together.

According to The Inter-America Development Bank, these smaller enterprises in Latin America suffered a financing gap of $1.8tn in 2017 – over five times the current credit supply to the sector, and the equivalent of 42% regional GDP2. Non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) emerged as an alternative for small companies and consumers looking to plug the gap. Many of them carved out a niche for themselves, providing mortgages, car loans, credit cards, microcredit, personal loans – or a mixture of these – to the unbanked.

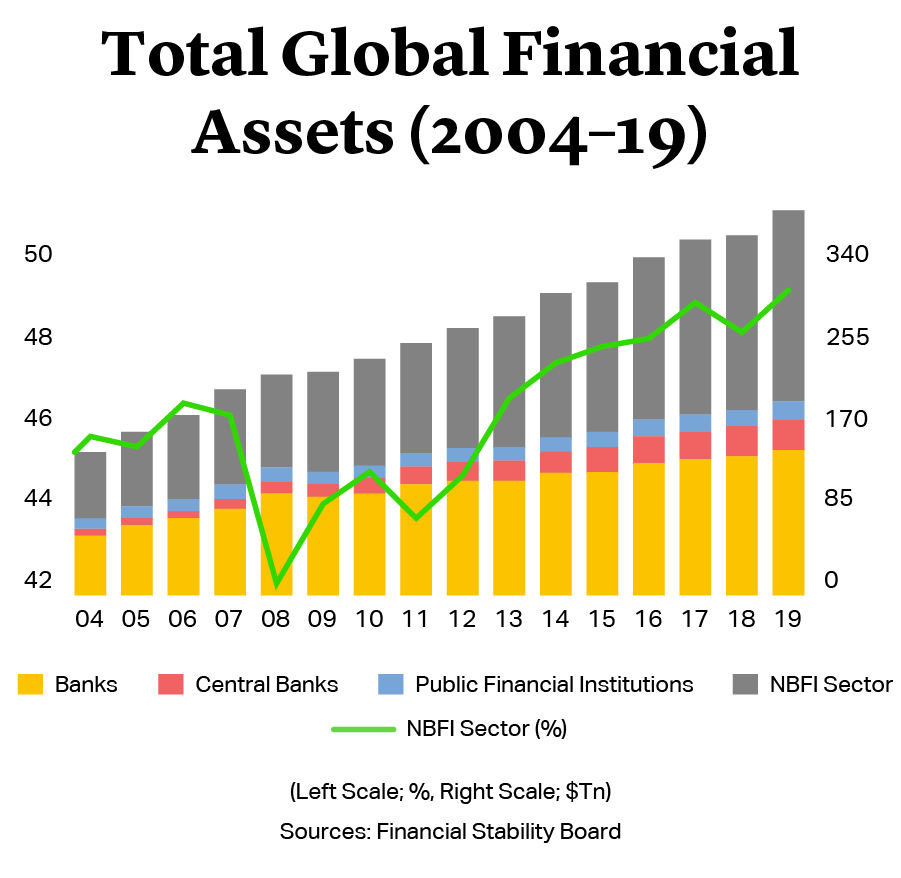

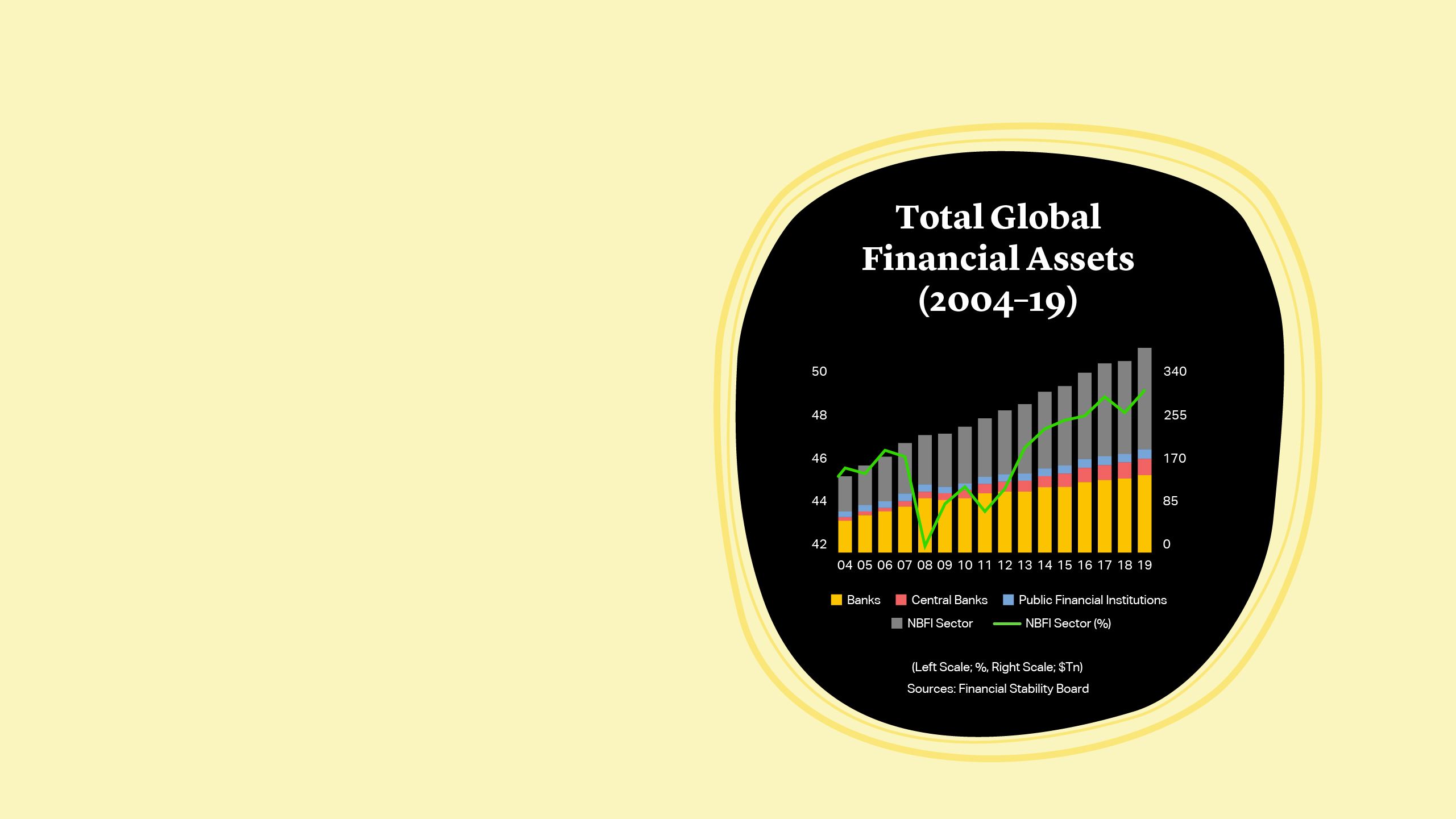

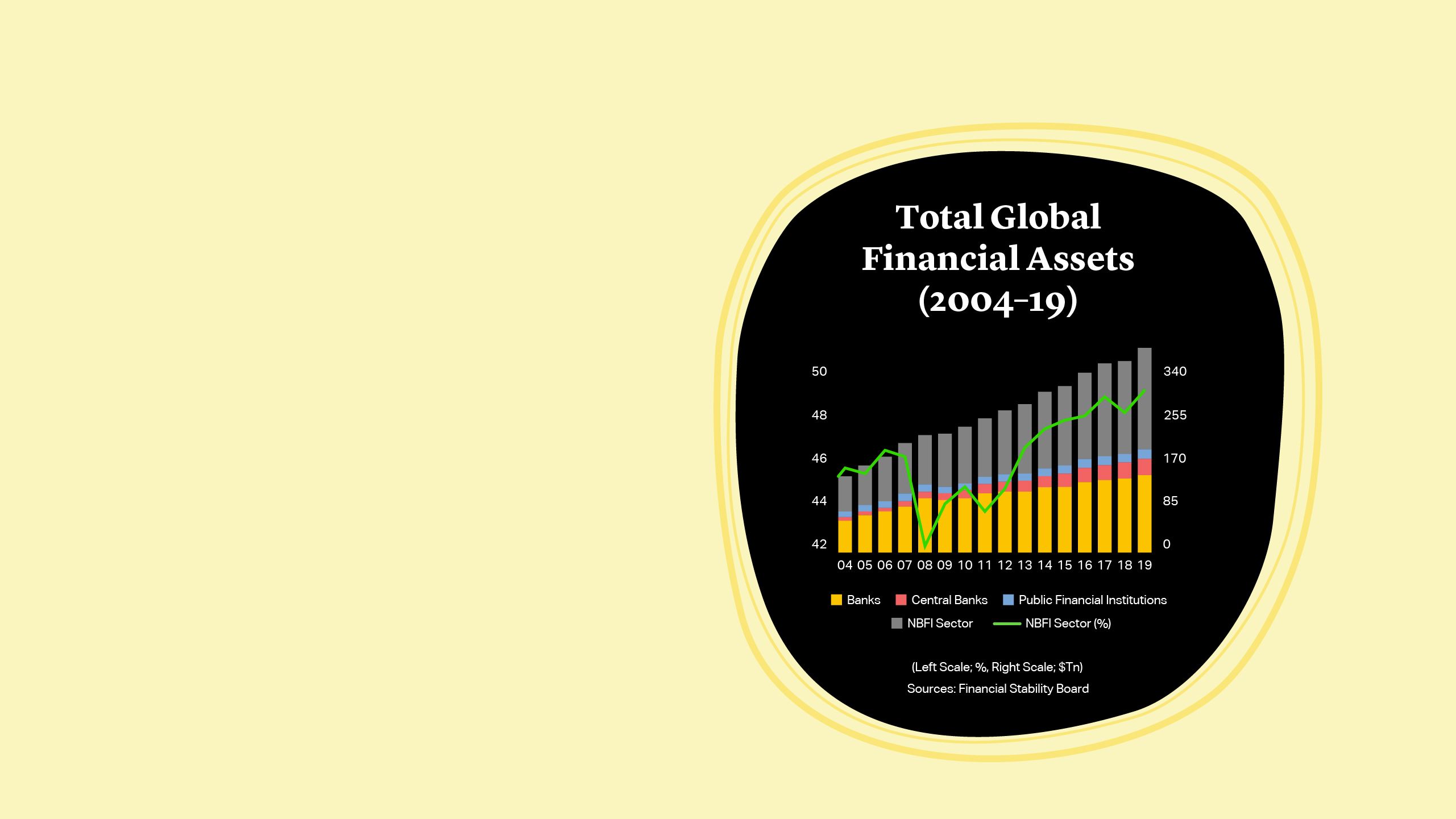

Little to no capital requirements, loose regulation, advances in technology and a captive market have allowed NBFIs to thrive Latin America. According to data collected by the Financial Stability Board, the NBFI sector grew by 8.9% to $200.2tn, accounting for 49.5% of total global financial assets in 2019 – outpacing the growth of banks within the same period3.

In Mexico, the sector has come into its own. According to central bank data, total non-bank lending for consumer credit, mortgages and company financing rose to 6.9tn pesos ($341bn) versus 5.2tn pesos ($257bn) for banks in the fourth quarter of 2020.

By creating a niche and serving underrepresented sectors of society, NBFIs have helped consumers access essential credit while boosting financial inclusion.

According to The Inter-America Development Bank, these smaller enterprises in Latin America suffered a financing gap of $1.8tn in 2017 – over five times the current credit supply to the sector, and the equivalent of 42% regional GDP2. Non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) emerged as an alternative for small companies and consumers looking to plug the gap. Many of them carved out a niche for themselves, providing mortgages, car loans, credit cards, microcredit, personal loans – or a mixture of these – to the unbanked.

Little to no capital requirements, loose regulation, advances in technology and a captive market have allowed NBFIs to thrive Latin America. According to data collected by the Financial Stability Board, the NBFI sector grew by 8.9% to $200.2tn, accounting for 49.5% of total global financial assets in 2019 – outpacing the growth of banks within the same period3.

In Mexico, the sector has come into its own. According to central bank data, total non-bank lending for consumer credit, mortgages and company financing rose to 6.9tn pesos ($341bn) versus 5.2tn pesos ($257bn) for banks in the fourth quarter of 2020.

By creating a niche and serving underrepresented sectors of society, NBFIs have helped consumers access essential credit while boosting financial inclusion.

The Cost of COVID-19

But what was once an avenue of opportunity is now a cause for concern. NBFIs focused on unsecured lending to low-income sectors of the economy run the risk of high-default rates, or worse, as stay at home mandates and supply chain issues caused by the global pandemic continue to stifle economic growth.

Asset deterioration and rising default rates are inevitable. They will, however, vary given the combination of economic deceleration, state-sanctioned support programmes, the shift in market sentiment and exposure in each country.

For instance, NBFIs that have made their money via payroll lending – where loan repayments are taken before salaries are distributed – may fare better than others, especially if they work with public sector institutions. But there is no hard and fast rule.

When the economy in Latin America slowed, Mexico-based AlphaCrédit, which carved out a niche for itself providing credit to small-to-medium sized enterprises, found that the sub-sovereign sector employers it served held back loan repayments via payroll to support their own businesses.

When auditors discovered an error in AlphaCrédit’s derivatives accounting and that 4.1bn pesos ($206mn) previously reported as other assets and accounts receivable could be impaired, investors were spooked. Other actors in the sector threw out more uncertainty, with revelations of underreported delinquency rates. On the back of these discoveries, the bond prices for issuers in the sector have plummeted.

Subsequent investigations into AlphaCrédit uncovered a culture of mismanagement and severe accounting issues that resulted in bankruptcy. While no wrongdoing has been uncovered within other entities in the sector as yet, NBFIs may be tainted by the AlphaCrédit scandal and face challenges when it comes to refinancing upcoming maturities due to contagion. Worse still, further investigation could uncover broader, industry wide accounting problems and more NBFIs may be forced to close.

Given the mounting pressure, credit ratings agency Fitch revised its sector outlook on Latin America NBFIs from ‘stable’ to ‘negative’ in March 20204. The move reflected downside risk to their credit profiles due to the pandemic and subsequent sovereign downgrade5.

The Cost of COVID-19

But what was once an avenue of opportunity is now a cause for concern. NBFIs focused on unsecured lending to low-income sectors of the economy run the risk of high-default rates, or worse, as stay at home mandates and supply chain issues caused by the global pandemic continue to stifle economic growth.

Asset deterioration and rising default rates are inevitable. They will, however, vary given the combination of economic deceleration, state-sanctioned support programmes, the shift in market sentiment and exposure in each country.

For instance, NBFIs that have made their money via payroll lending – where loan repayments are taken before salaries are distributed – may fare better than others, especially if they work with public sector institutions. But there is no hard and fast rule.

When the economy in Latin America slowed, Mexico-based AlphaCrédit, which carved out a niche for itself providing credit to small-to-medium sized enterprises, found that the sub-sovereign sector employers it served held back loan repayments via payroll to support their own businesses.

When auditors discovered an error in AlphaCrédit’s derivatives accounting and that 4.1bn pesos ($206mn) previously reported as other assets and accounts receivable could be impaired, investors were spooked. Other actors in the sector threw out more uncertainty, with revelations of underreported delinquency rates. On the back of these discoveries, the bond prices for issuers in the sector have plummeted.

Subsequent investigations into AlphaCrédit uncovered a culture of mismanagement and severe accounting issues that resulted in bankruptcy. While no wrongdoing has been uncovered within other entities in the sector as yet, NBFIs may be tainted by the AlphaCrédit scandal and face challenges when it comes to refinancing upcoming maturities due to contagion. Worse still, further investigation could uncover broader, industry wide accounting problems and more NBFIs may be forced to close.

Given the mounting pressure, credit ratings agency Fitch revised its sector outlook on Latin America NBFIs from ‘stable’ to ‘negative’ in March 20204. The move reflected downside risk to their credit profiles due to the pandemic and subsequent sovereign downgrade5.

Time for Change

NFBIs make their money through loan origination, but in a stress scenario, whether because of increased delinquency in their own portfolios or simply because of sector-wide contagion, they can no longer issue debt, which means that their business model no longer works. Restructuring the small loans granted by NBFIs – extending repayment terms or adjusting interest rates – may offer short term relief to borrowers unable to repay loans while keeping lenders’ balance sheets clean and default rates low, but this will only delay the inevitable decline of their business (and, in some cases, can be used to manipulate delinquency ratios). New origination may not be able to fill the gap either, given that many consumers are unwilling to apply for credit given the current economic downturn.

Muddying the water further, there have even been issues around the validity of existing NBFI loans. While technology has allowed them to issue loans faster than before, questions abound on how to legally enforce a digitally issued loan. Combine this with a sector that is notoriously bad at maintaining transparent and up to date accounts, and it’s evident that more of these loans could be disputed or written off.

Another option may be for state governments to create a bad bank equivalent for NBFIs – but this requires political will. Given that NBFIs are not “too big to fail” like their commercial bank counterparts, there is little pushing governments to save these types of institutions. In Mexico, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s austerity push slashed Mexico’s Comision Nacional Bancaria de Valores (CNBV) budget6. It might be that governments and central banks lack capacity and spending power.

In fact, allowing these institutions to collapse, and eradicating the debt of constituents, may be a popular policy move, given the economic and financial pressure the electorate in Latin America are currently under. In any case, politicians do not have the fiscal space to save NBFIs as they continue to grapple with the economic and financial fallout of the global pandemic in other sectors.

At some point, NBFIs will need capital. The strongest of them will be able to access the capital markets, where interest rates remain low and attractive to borrowers. For others, however, consolidation may be the only viable solution.

We have seen similar trends in other emerging markets. In Sri Lanka, the Central Bank announced a five-year consolidation plan for the NBFI sector. In India, a similar pattern of consolidation occurred for nearly 10 years in response to a rise in non-performing assets within the sector. In Latin America, acquisitions of loan portfolios and consolidation of smaller NBFIs has already started and may continue in years to come. It may be the only way the industry will survive.

Time for Change

NFBIs make their money through loan origination, but in a stress scenario, whether because of increased delinquency in their own portfolios or simply because of sector-wide contagion, they can no longer issue debt, which means that their business model no longer works. Restructuring the small loans granted by NBFIs – extending repayment terms or adjusting interest rates – may offer short term relief to borrowers unable to repay loans while keeping lenders’ balance sheets clean and default rates low, but this will only delay the inevitable decline of their business (and, in some cases, can be used to manipulate delinquency ratios). New origination may not be able to fill the gap either, given that many consumers are unwilling to apply for credit given the current economic downturn.

Muddying the water further, there have even been issues around the validity of existing NBFI loans. While technology has allowed them to issue loans faster than before, questions abound on how to legally enforce a digitally issued loan. Combine this with a sector that is notoriously bad at maintaining transparent and up to date accounts, and it’s evident that more of these loans could be disputed or written off.

Another option may be for state governments to create a bad bank equivalent for NBFIs – but this requires political will. Given that NBFIs are not “too big to fail” like their commercial bank counterparts, there is little pushing governments to save these types of institutions. In Mexico, President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador’s austerity push slashed Mexico’s Comision Nacional Bancaria de Valores (CNBV) budget6. It might be that governments and central banks lack capacity and spending power.

In fact, allowing these institutions to collapse, and eradicating the debt of constituents, may be a popular policy move, given the economic and financial pressure the electorate in Latin America are currently under. In any case, politicians do not have the fiscal space to save NBFIs as they continue to grapple with the economic and financial fallout of the global pandemic in other sectors.

At some point, NBFIs will need capital. The strongest of them will be able to access the capital markets, where interest rates remain low and attractive to borrowers. For others, however, consolidation may be the only viable solution.

We have seen similar trends in other emerging markets. In Sri Lanka, the Central Bank announced a five-year consolidation plan for the NBFI sector. In India, a similar pattern of consolidation occurred for nearly 10 years in response to a rise in non-performing assets within the sector. In Latin America, acquisitions of loan portfolios and consolidation of smaller NBFIs has already started and may continue in years to come. It may be the only way the industry will survive.