Do Keepwell

Agreements

Actually Keep

You Well?

The financial difficulties currently faced by China’s Evergrande Group have thrown light on a relatively obscure form of credit enhancement – the keepwell agreement. Despite the fact that billions of dollars of ‘offshore’ debt has been raised by Chinese companies using this structure, there is still a high degree of uncertainty as to whether keepwell agreements represent an enforceable form of credit support. The answer to that question may well end up being the determining factor in the likely recovery value of Evergrande’s offshore debt.

What Is a Keepwell?

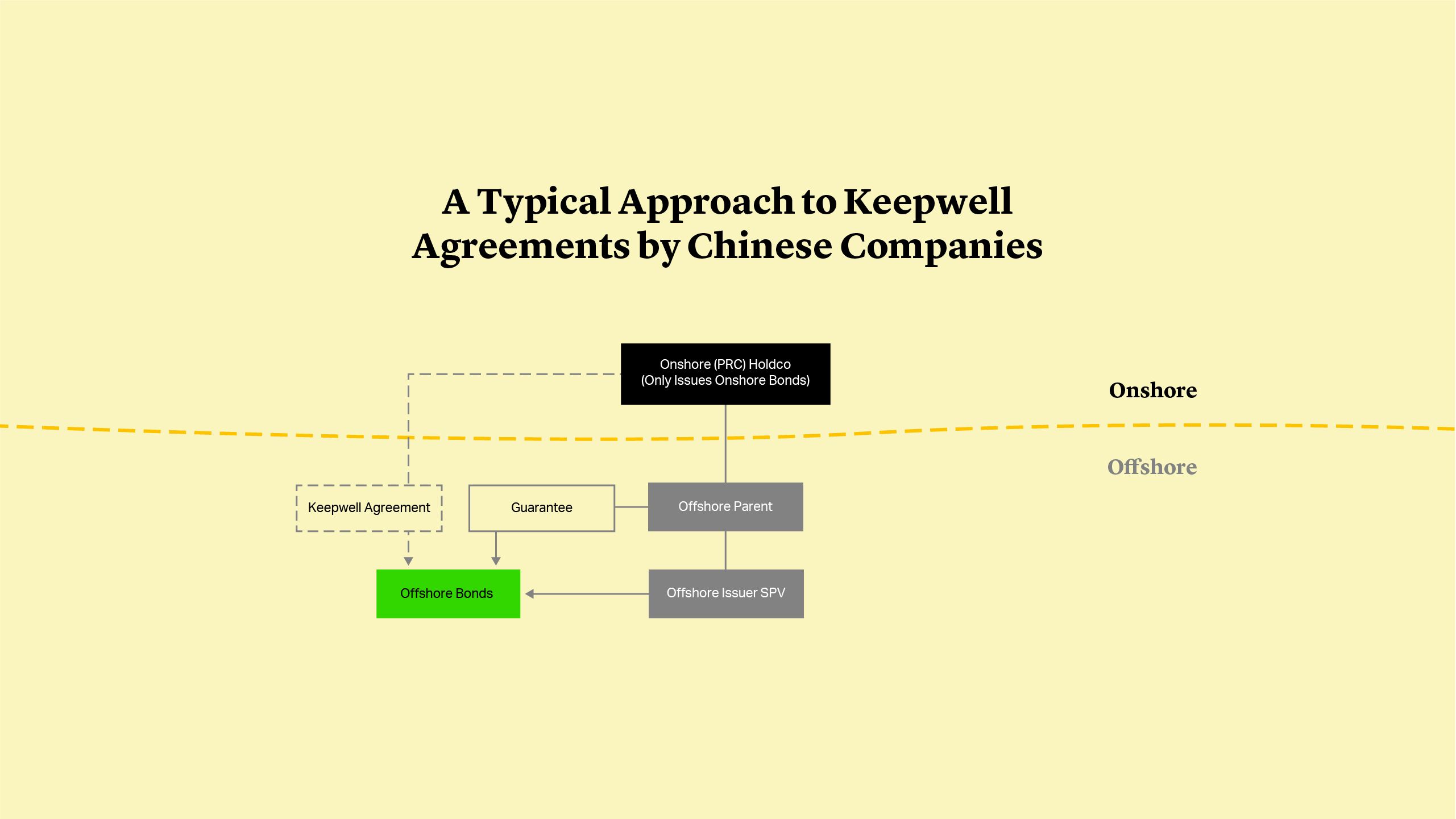

A keepwell agreement is a form of credit enhancement which is typically provided by a Chinese corporate to support an issue of bonds by its offshore subsidiary. These agreements have become popular due to the regulatory difficulty that Chinese companies have in providing parent guarantees. This includes a law requiring that any guarantee given by a Chinese company in respect of its offshore subsidiaries’ debt must be registered with the PRC State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) within 15 days of its issuance. The registration process is relatively opaque, and a refusal of registration would make it illegal for the guarantor to remit funds abroad to comply with the guarantee.

Despite some suggestions that SAFE has recently become more willing to allow onshore companies to guarantee their offshore subsidiaries’ debt1, strict restrictions on this practice since 2014 have led to the widespread use of keepwell agreements. By most estimates, around 15-16% (or $93-96bn) of overseas bonds issued by PRC-funded enterprises (largely in 2016-2017) have been accompanied by a keepwell agreement, most of which are governed by New York, English or Hong Kong law.

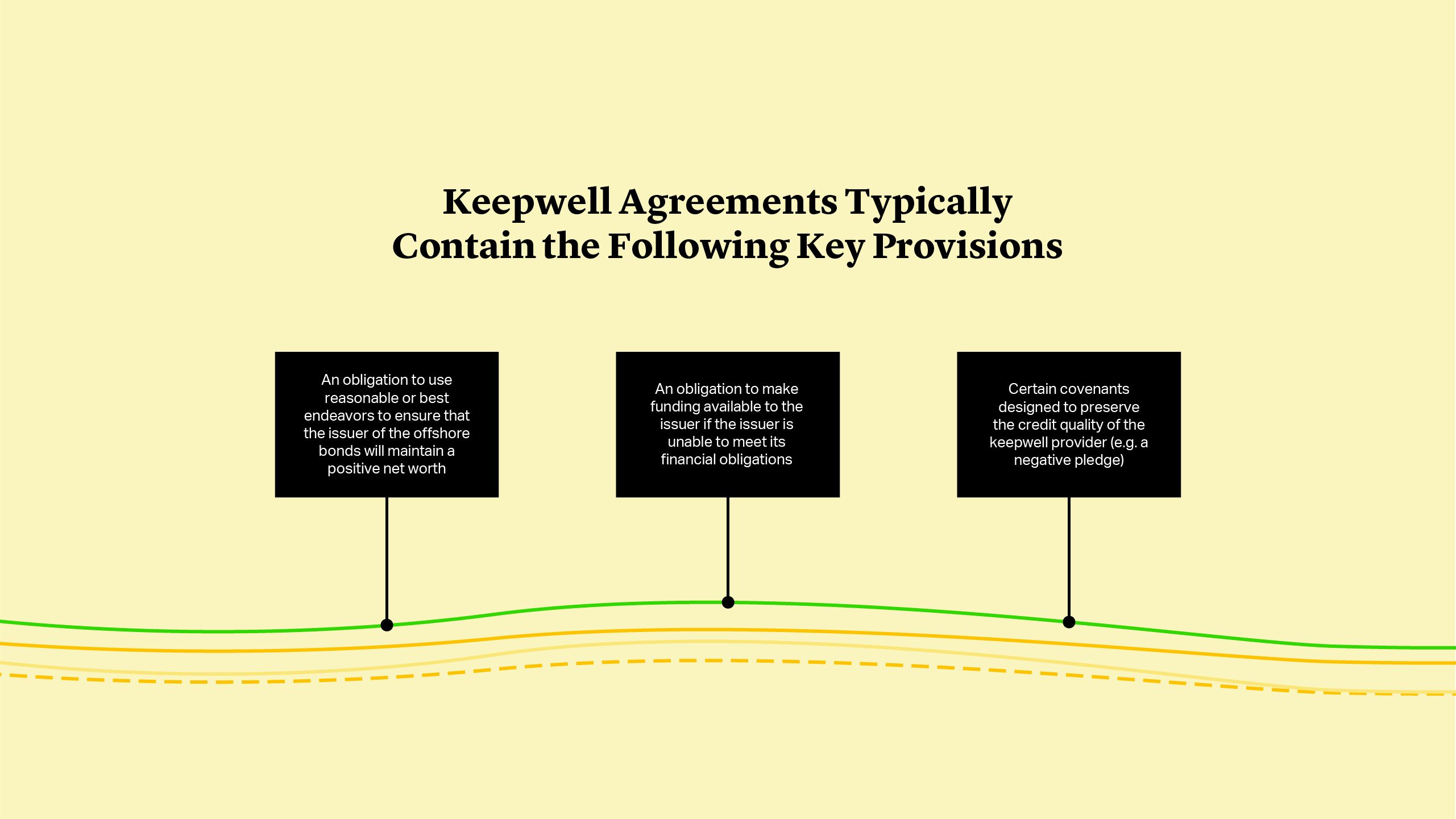

However, most keepwell agreements will explicitly say that they are not guarantees and that they do not create a direct obligation to repay the amount the issuer owes to bondholders. Importantly, they can also say that any obligation to assist the issuer is subject to any necessary regulatory approvals.

Enforcement Challenges

Enforcing a parent guarantee is fairly straightforward – usually the creditor simply makes a written demand and the debt becomes due. If it’s not paid, the creditor can usually seek summary judgment from the appropriate court. However, enforcing a keepwell agreement is more difficult as there is no direct payment obligation to the creditor. This means the remaining options are either to seek specific performance of the parent company’s obligation to put the issuer in funds to satisfy the issuer’s obligations; or sue for damages caused by the parent company’s failure to comply with its obligations.

Specific performance orders are often difficult to obtain because the creditor would need to show that damages are not an adequate remedy. In addition, if the keepwell obligation is qualified by reference to regulatory approvals, it may be that the parent company is able to avoid being liable at all by showing that a government approval had been withheld. A damages claim also has its challenges because the creditor needs to show that it was the breach of the keepwell that caused the damage it suffered.

These arguments would need to be made – and won – in the courts of the country whose law governs the keepwell agreement. This is typically England, Hong Kong or New York, because creditors would prefer to avoid having to enforce their claims directly in PRC courts. In the case of Hong Kong law, creditors may also be able to take advantage of the smoother recognition process for judgments in the territory. Yet, if the arguments are successful, judgments still need to be recognized by the courts of the country where the provider of the keepwell agreement is incorporated, usually China. This is where most of the uncertainties lie.

Getting to the Assets

The difficulties around keepwell agreements stem from the fact that there are two key grounds on which the provider of these structures could raise as defenses in a Chinese court.

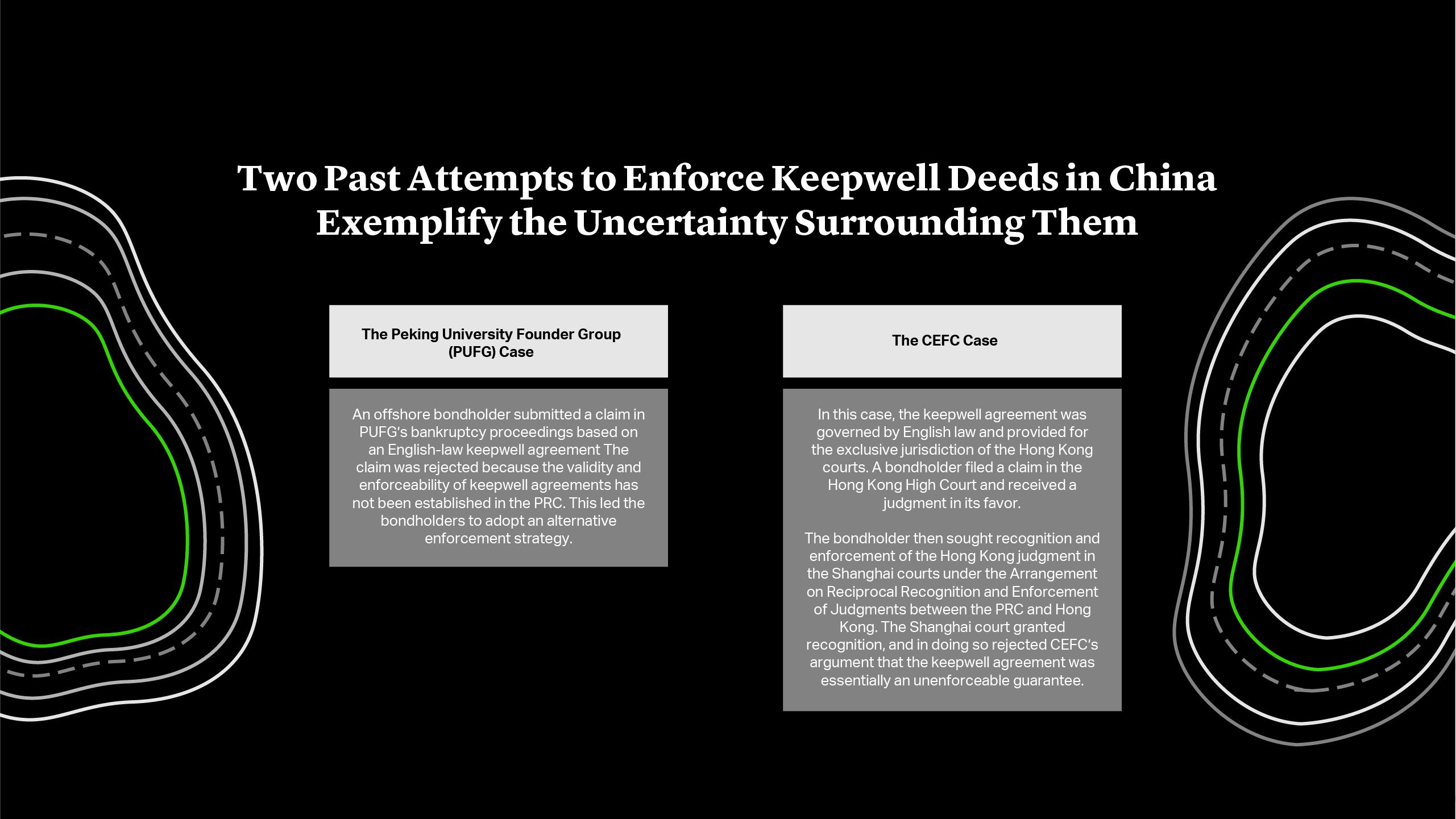

First is the argument that the keepwell arrangement is in fact a guarantee that the court should refuse to enforce since it was not registered with SAFE. The strength of this argument may depend, to some extent, on the optics. If the enforcement action is being brought by a bondholder or the bond trustee, it lends credence to the argument. That has led to suggestions that a more circuitous enforcement strategy may be required.

Secondly, Chinese courts have a broad discretion to refuse to recognize the judgments of foreign courts on the grounds of public policy. Market participants have speculated that a Chinese court is likely to use this discretion if recognizing a foreign judgment would have the effect of providing a better recovery to foreign creditors than domestic. That concern is particularly acute in the case of Evergrande, since many of the domestic creditors are private citizens.

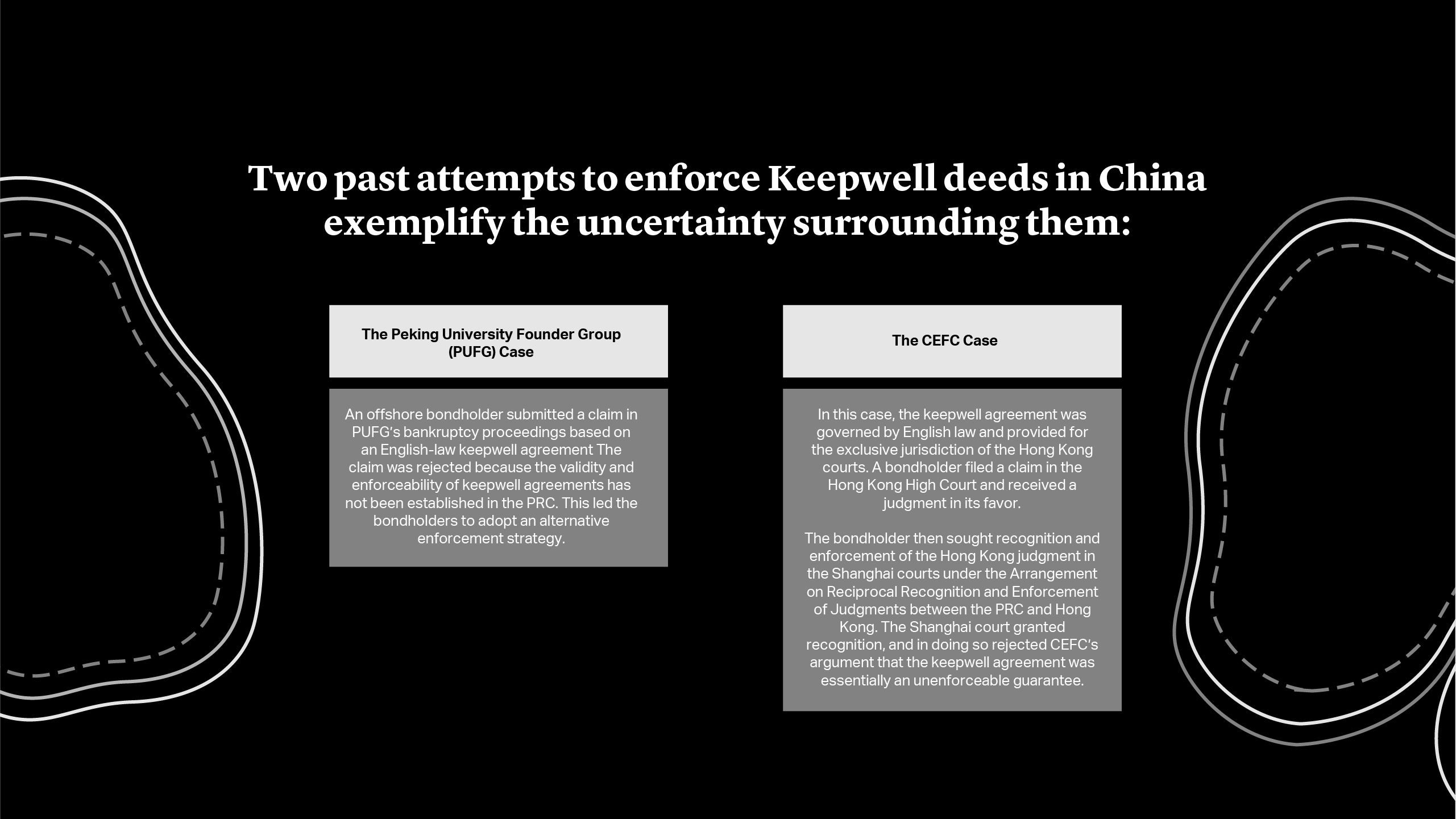

The creditors in the CEFC case were able to sidestep these arguments by relying on the mutual judgment recognition regime in place between Hong Kong and China. This is why the Shanghai court did not concern itself with substantive aspects of the keepwell agreement. But the CEFC case may not actually provide creditors with a huge amount of comfort.

This is primarily because there is no system of case law precedent in the PRC. Just because one court has taken a particular approach, does not mean that any other court is required to follow suit. The CEFC situation may also have been a one-off: the enforcing creditor in that case was a state-owned-entity, while the amount at stake was relatively small and the CEFC did not oppose the enforcement action in Hong Kong. Whether the PRC courts will allow such a frictionless process in more contentious cases remains to be seen.

In relation to judgments from New York and English courts, the route to recognition is less clear. In addition to the public policy requirement, a PRC court will only enforce a judgment if reciprocity exists. Despite initial reluctance, some Chinese courts have enforced judgments from U.S. courts in recent decisions on the basis that a reciprocal relationship is in place. However, even if a Chinese court was prepared to agree on the reciprocity point, it will still require the foreign judgment to be ‘legally effective’. That could be interpreted to mean that it must be final, requiring all appeal processes in the relevant courts to have been exhausted. This will have timing and cost implications.

Alternative Strategies

However, bondholders could adopt one of two alternative enforcement strategies. These include:

Both of these options can be pursued in parallel – a so-called ‘dual track’ approach. This strategy leaves open the possibility of a double recovery. Since the bondholders are not enforcing on a guarantee, their recoveries need not be limited to the amount of the guaranteed debt.

This is ultimately the approach bondholders took in the PUFG case after the administrators of the debtor had rejected their direct claims. They put the bond issuer into liquidation, the liquidator sought recognition of the keepwell claims and, at the same time, they pursued a tracing claim.

Conclusion

The extent to which a keepwell agreement can be enforced against an onshore parent is clearly critical to the calculation of the recovery value on the underlying debt. As offshore bonds continue to become distressed, the uncertainty surrounding keepwell agreements acts as an additional weight on the secondary market price. In many cases, that price will eventually reach a level where there is real option value, and investors will be prepared to buy in even if the legal recourse is not wholly robust.