While Africa has largely avoided severe health implications, COVID-19 may have placed its export-driven market at the centre of the next emerging markets’ debt crisis.

Assistance such as the Paris Club/G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) is available, but there has been little action beyond simple payment postponement. While few jurisdictions are close to economic default, the region’s growing commercial lending – over 20 African countries now issue Eurobonds – will make full economic recovery significantly harder.

Relief to Date: Political Problems Collide with Commercial Terms

So far, just three DSSI-eligible countries have requested relief from private-sector bondholders to lukewarm response. Private creditors have argued Africa knew the risks and writing down lending would be unfair to their own investors and set a dangerous precedent.

This is a political, as much as an economic crisis. Governments often wasted funds raised, in plain sight of investors. In Africa’s most distressed states – Zambia and Angola – political transparency is essential to bringing the private sector on board with restructuring efforts.

Zambia: Political Mismanagement and

Debt Default

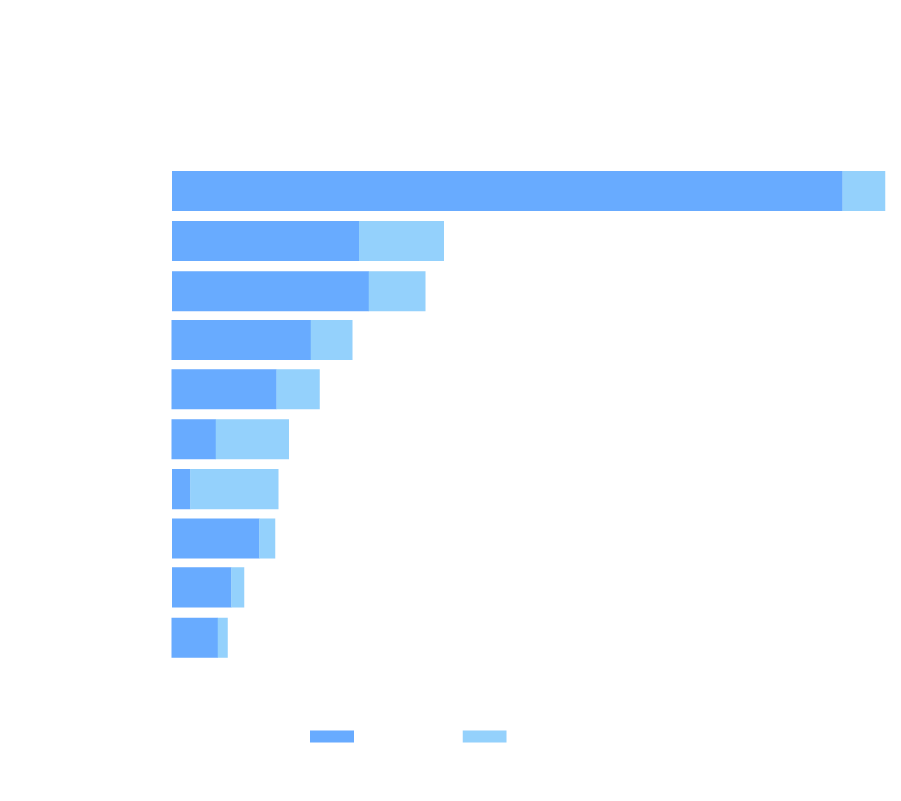

Zambia, Africa’s only default to date, is atypical. Since 2011, government debt has risen from 21 to 120% of GDP – much of it in 10-year Eurobonds. When the global commodities’ bubble burst in 2014, Zambia only doubled down on its aggressive borrowing strategy, despite repeated IMF warnings. COVID-19’s damage to Zambia’s copper exports market has accelerated an inevitable reckoning on the country’s debt crisis.

The Government hired Lazard in May 2020, to advise on restructuring, but bondholder negotiations have stalled and engagement with the IMF has gone nowhere. President Edgar Lungu further damaged investor confidence in August, byreplacing central bank governor Denny Kalyalya, with close ally, Christopher Mvunga.

Transparency is a huge concern. Speculation has been rife for years of state-owned Zambian assets being collateral for Chinese loans. Zambia adopted a ‘take it or leave it’ approach with Eurobond holders, proposing an interest payment deferral, in September, while keeping parallel negotiations with Chinese creditors under wraps. Bondholders, many of them able to sue on a bond-by-bond basis, unsurprisingly, rejected the plan, prompting November’s default.

Angola: Restoring International Trust?

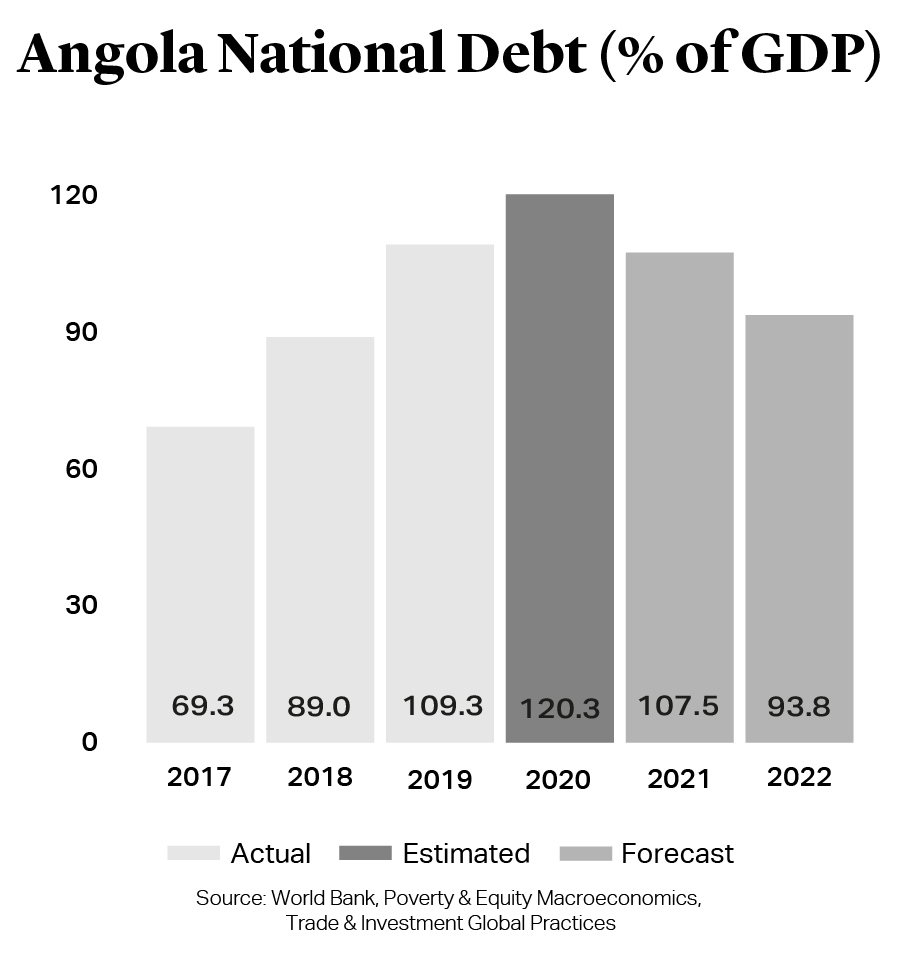

Angola arguably entered the crisis with bigger problems than Zambia. Former president Jose Eduardo dos Santos’ mismanagement and corruption created an oil-dependent economy, and 2014’s falling prices proved devastating, with national debt projected at 130% by the end of 2020.

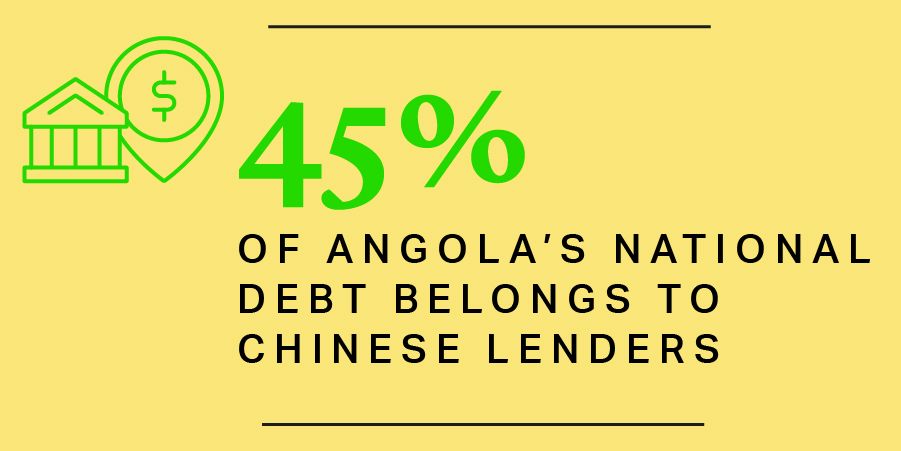

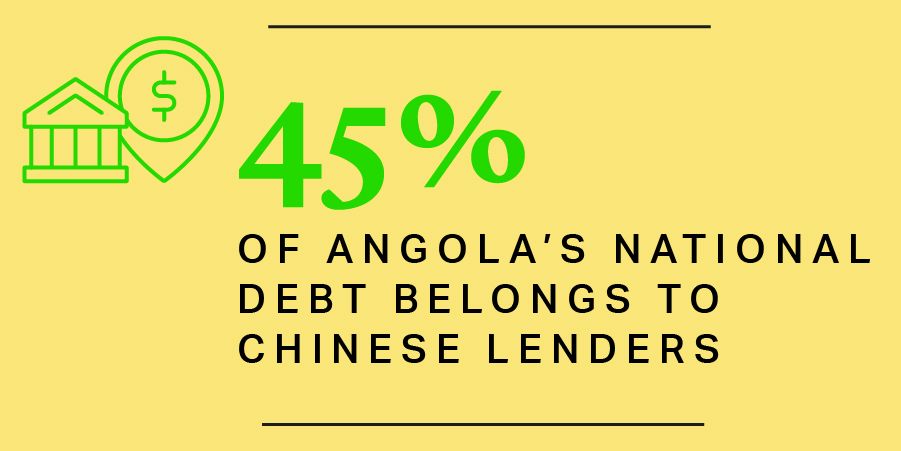

Unlike Zambia, however, Angola has focused on realistic long-term recovery, and should avoid sovereign default in the short-term. The IMF approved a further tranche of USD$1bn in funding in September, following the government’s commitment to tax reform and progress in creditor negotiations. Around 45% of Angola’s national debt belongs to Chinese lenders, but it reportedly reached deals with the largest creditors, China Development Bank and Eximbank, in September. By avoiding ill-will negotiations with Eurobondholders, Angola still has the option of further Eurobond issuance available for emergencies.

Angola: Restoring International Trust?

Angola arguably entered the crisis with bigger problems than Zambia. Former president Jose Eduardo dos Santos’ mismanagement and corruption created an oil-dependent economy, and 2014’s falling prices proved devastating, with national debt projected at 130% by the end of 2020.

Unlike Zambia, however, Angola has focused on realistic long-term recovery, and should avoid sovereign default in the short-term. The IMF approved a further tranche of USD$1bn in funding in September, following the government’s commitment to tax reform and progress in creditor negotiations. Around 45% of Angola’s national debt belongs to Chinese lenders, but it reportedly reached deals with the largest creditors, China Development Bank and Eximbank, in September. By avoiding ill-will negotiations with Eurobondholders, Angola still has the option of further Eurobond issuance available for emergencies.

International Action: Growing Pressure on the Private Sector?

The IMF is increasingly frustrated with private creditors’ failure to participate in the DSSI. The G20’s newly-released common framework on debt relief and restructuring is likely to place them under further pressure. The IMF and World Bank have both signalled a desire to initiate case-by-case sovereign debt-stock reduction in 2021, with neither looking favorably on private creditors failing to step up. Overall, private creditors need to consider the implications inflexibility could have for future commercial lending opportunities.

Outlook: Short-term Loss for Long-term Gain?

No further African sovereigns are in imminent default danger, and while Angola’s position is precarious, its positive action to date places it in good stead. Private creditors, meanwhile, must consider the long-term consequences of their actions. While taking a write-down on an investment is always disappointing, a strong post-pandemic Africa offers its own rewards to those who support restructuring efforts.

Simiso Velempini

CEO, Africa Matters

As the CEO of AML, Simiso leads the strategic direction and growth of Africa Matters. She has extensive consulting and advisory experience in sub-Saharan Africa and is frequently used as a sounding board by senior public and private sector leaders.